“‘Are these the Nazis, Walter?’ ‘No, Donnie, these men are nihilists. There’s nothing to be afraid of.'” Moments before Donnie’s tragic death,a Walter assures Donnie that the nihilists won’t hurt them: “No, Donnie, these men are cowards.”

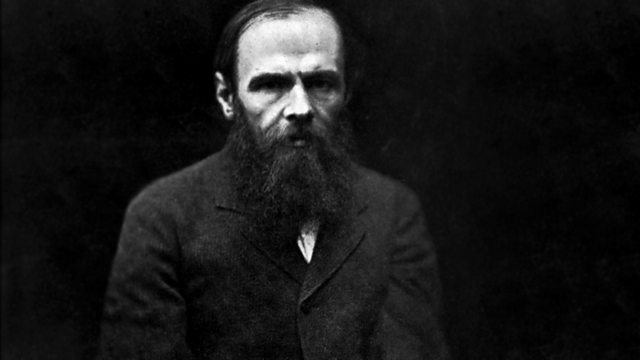

Fyodor Dostoevsky, on the other hand, took the threat of nihilism more seriously than The Big Lebowski’s Walter. Perhaps that was, in part, because he was once a nihilist himself. Before his exile in Siberia, Dostoevsky was part of a group of young radicals. His activity with the progressive Petrashevsky Circle led to their arrest and a death sentence that was commuted at the last moment. His time in exile proved transformative. Enduring suffering with his copy of the New Testament as his only comfort, he emerged from exile a devout Orthodox Christian and Russian conservative.

Since this past Summer, the United States has witnessed nihilism run amok on our streets. Literal mobs bent on destruction have been allowed to have their way with American cities. Of course this didn’t come out of nowhere; this movement has been fomenting and picking up steam for some time now, but this year it seems to have maintained energy in a new way.

Our Dostoevskian Moment

Back in July, Rod Dreher, drawing from an article by Daniel Mahoney, described what we are seeing now as “America’s Dostoevskian Moment”. We are facing in our day the same kind of destructive fervor, the same kind of nihilism, that Dostoevsky predicted in his novel Demons would lead to the death of 100 million Russians if the revolutionaries come to power. History has proved that he knew what he was talking about.

Mahoney makes a compelling argument, and I encourage the reader to visit his article. We face an election coming on Tuesday, the results of which are sure to be hotly contested, in an already heated political climate. Whichever way the election goes, our contemporary nihilists are set on violence and destruction. We have learned that we cannot count on civic leaders to protect property or lives. What are we to do?

That this is the case seems beyond dispute. My purpose in writing is to consider Dostoevsky’s alternative to nihilism in the narrative of Demons, and how that might inform us as we face similar forces in our day.

A New Cry

In his typical style, Dostoevsky does not mount a formal argument against nihilism. Rather he embeds his argument in the narrative. One of my favorite passages in Dosoevsky centers on Shatov, a character in Demons who has turned away from his former revolutionary ideals and embraced Christ. He accepts suffering as he is singled out to be a scapegoat by his former associates. In this passage, his estranged wife, Marie, returns to him, pregnant by another man, ready to give birth. Shatov fetches Arina Prokhorovna, a local midwife. Waiting outside the room while Marie labors, he then hears “a new cry”:

And then, finally, there came a cry, a new cry, at which Shatov gave a start and jumped up from his knees, the cry of an infant, weak, cracked. He crossed himself and rushed into the room. In Arina Prokhorovna’s hands a small, red, wrinkled being was crying and waving its tiny arms and legs, a terribly helpless being, like a speck of dust at the mercy of the first puff of wind, yet crying and proclaiming itself, as if it, too, somehow had the fullest right to life…

‘Pah, what a look!’ the triumphant Arina Prokhorovna laughed merrily, peeking into Shatov’s face. ‘Just see the face on him!’…

‘What’s this great joy of yours?’ Arina Prokhorovna was amusing herself, while bustling about, tidying up, and working like a galley slave.

‘The mystery of the appearance of a new being, a great mystery and an inexplicable one, Arina Prokhorovna, and what a shame you don’t understand it!’…

‘There were two, and suddenly there’s a third human being, a new spirit, whole, finished, such as doesn’t come from human hands; a new thought and a new love, it’s even frightening… And there’s nothing higher in the world!'” b

This new cry of life, Shatov’s exuberance over this new being, is Dostoevsky’s contrast to the destructive ideals of the nihilists. This new life is the light in the darkness of the narrative of Demons. And new life, New Creation, must be the light we shine in the face of our nihilistic mob, in what feel like dark days in our own culture.

On one level, the way we do this is simply by valuing precisely what Shatov rejoices over: the new life of the most weak and vulnerable, infant life crying out, proclaiming itself. Simply opposing the slaughter of the unborn incites the mobs against us, as is clearly being played out in Poland now.

The Risen Christ is the light that breaks the darkness, new life liberating those held captive under the bonds of death. As St. Paul says in His “Christ Hymn” to the Colossians,

And He is the head of the body, the Church.

He is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead,

That in everything He might be preeminent…c

He is the firstborn, and we, the Church, follow in His new creation life. We bring the reality of Christ’s reign, of His new creation, to bear on the world. Dostoevsky believed we best do this by joyfully suffering in Christ. St. Paul would agree: just as Christ “humbled Himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on the Cross,” so we are to follow Him, taking up our cross, participating in Christ’s suffering, so that we may “shine as lights” in the midst of our “crooked and twisted generation.”d Suffering with joy, living lives of gratitude, of feasting, of abundant hospitality: this abundant resurrection life is how we confront our culture’s nihilistic love for death and destruction. So stop wringing your hands about the plight of our nation, and start get to work forming deeply joyful communities in your church life, family, and neighborhood.

Try to vote in the guy you think will do the most to defend life, preserve peace, punish the wicked, defend freedom. Work for God-honoring public policy. Engage in debates, make the case for the Faith. But our ultimate “strategy” must be the way of the Cross. Christ and Him crucified is the light that breaks the darkness, shining through the lives of His saints. That is how the Church turns the world upside down.

- It’s been 22 years since The Big Lebowski came out. The time for spoiler alerts is over. (back)

- Dostoesky, Fyodor. Deomons. New York, Everyman’s Library, 1994. p. 592-3 (back)

- Col. 1:18 (back)

- Phil. 2 (back)

Loved this post. So relevant, in my country, South Africa, too. I posted it on my Facebook page, The Sharp Souith African Culture Forum.