The task of speaking for Christ in the public square – the kind of thing done here in the UK by our friends at Christian Concern and the Christian Institute – is an urgent and important one. Yet it is fraught with difficulties. Here are some of them.

1. The British evangelical and Reformed church has given only limited attention to the task of constructing a public theology. Many churches appear to view almost any kind of public engagement as a distraction from the gospel, a view that only serves to reveal an unbiblical and minimalist view of the gospel itself. Yet the fact remains that with a few exceptions British evangelical and Reformed churches are largely disengaged from public life, leaving the task to courageous para-church organisations like those mentioned above. One reason for this is that we have failed to articulate a clear theological rationale for such engagement. Consequently, until we recover something approaching a biblical view of eschatology, ecclesiology, and indeed of the gospel itself, this situation is unlikely to change.

My impression is that the situation is a little better in the US. Yet even so, I’m not sure there are many reasons for optimism. Just to take one slightly unnerving example, if a Christian-dominated political constituency is capable of bringing this man to the brink of the nomination for Republican presidential candidate, it clearly has some way to go before it can really be said to have worked out all the details of its public theology.

2. Even for those who do get involved, there is a danger of making an over-simplified response to particular ethical issues. This danger is exacerbated both by the lack of a clear public-theological framework, and also by the media’s demand for wikipedia-level simplicity and trite yes/no answers even on exceedingly complex issues such as end-of-life care, divorce, capital punishment, and so on. Such knee-jerk responses have a short-term benefit of getting some kind of “Christian response” in the media, but create difficulties in the longer term when the complexities of the issues become apparent in other contexts. Is it any surprise that Christians are ridiculed by the participants of more nuanced ethical debates when we have allowed ourselves to be caricatured in 30-second soundbites on the BBC Today programme?

3. Our presence in the secular media, though allowing a (limited?) platform for (oversimplified) statements of our view, nonetheless leaves us hostage to the media’s caricature of the social constituency from which our views come. The secular media often seems to want someone to represent the “Crazy Christian Crowd” as an aspect of their narrative of a well-rounded, sane, socially-aware progressive movement gradually pushing back against centuries of ignorant Christian bigotry. We appear to be caught between a rock and a hard place: we either keep away from the secular media altogether and risk being completely ignored, or we engage in the debate in much the same way that a punchbag engages in a boxing match.

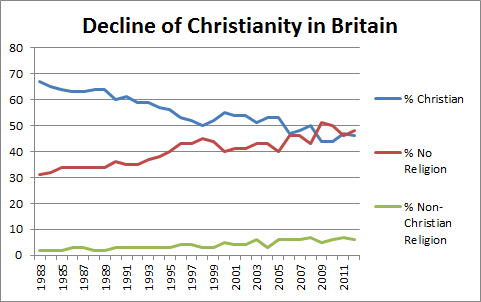

4. Christians are often alerted to particular issues by proposed changes to the law, failing to recognise that such proposals simply reflect broader social changes that have been taking place within the population for years, if not decades, previously. To take one example, British Christians did not “lose the battle on same-sex marriage” in March 2013; we lost it step by step from the mid-1960s onwards in a series of profound social changes that gradually unpicked the biblically-based framework for family life that had existed in law for centuries before this. These social changes themselves were (arguably, though without doubt in my view) only possible because of the church’s failure to live, worship, and proclaim the gospel faithfully for a century or more before this.

5. The previous two points might be enough to cause despair. Yet this conclusion is unwarranted. Instead, consider some questions:

- How is God at work to change the world? Through the media? Or through the church?

- According to the Bible, to what does God respond – people who shout loudly in the public square, or people who re-commit themselves to the faithful worship of the one who directs the hearts of kings and princes, to whom the nations of the world are a drop in a bucket? Perhaps the answer is both. Certainly the answer is not only, or even primarily, the former.

- If the unravelling of our social fabric came about through several generations of presumption followed by apostasy followed by outright rebellion, is it possible that the work of social reformation may take an equally long period of time?

- And if the rot began in the first instance at the house of God, is it not possible that Reformation, also, may begin here?