During my daily prayer regimen, I read through the New Testament at morning prayer and the Old Testament in the evening, one chapter at a time. At evening prayer I am now making my way through the two books of Chronicles, which many believe form a unit with Ezra and Nehemiah, composed after the return from Babylonian exile, possibly by Ezra himself.

When I’ve read Chronicles in the past, I’ve sometimes thought that they are redundant, simply repeating what the books of Samuel and Kings had already recounted. In the larger biblical narrative, it feels as though the story, which thus far has been smoothly told from Genesis to the exile, is suddenly interrupted by an apparently unnecessary flashback, taking us all the way back to, well, Adam, the first human being. Then we are treated to a long series of proper names, some of whom are familiar but most of whom are not, leaving us wondering what relevance they could possibly have to the larger story of salvation. What harm would have been done by leaving them out and simply skipping from 2 Kings to Ezra?

In fact, the two books of Chronicles are most important. In the Jewish Bible they come at the very end of the collection, functioning as both recap and capstone, leaving the reader with a sense of expectation and hope. In the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate, the books are called Paraleipomenon, which implies that the material therein supplements the books of Kings. Yet the Chronicles do not merely fill in the gaps in other books. The Chronicler brings to his work a distinctive emphasis which makes it more than just another historical account. In this we see an analogy to the four gospels, each of which brings a different perspective to Jesus’ life. It is often said that Mark tells us what Jesus did, Matthew and Luke tell us what he said, and John tells us who Jesus is. Together they provide a fuller understanding of Jesus’ life and ministry than only one gospel could do, much as two eyes convey depth in a way that one eye cannot.

So why two accounts of the reigns of the kings and not a repetition of, say, the Exodus narrative or the conquest of Canaan? What was God’s intention—as opposed to the original author’s intention—in inspiring the writer to recount this material a second time? I believe a clue can be found at the very beginning of Matthew, which starts with “Jesus Christ, the son of David.” By then the expectation that the coming Messiah would be a son of David had an ancient pedigree. Both Matthew and Luke contain Chronicles-like genealogies emphasizing Jesus’ descent from the royal Davidic line. Throughout the Bible, David is not just another king. He is the ideal monarch, a precursor to the promised Messiah, who will save his people from their sins and usher in a new kingdom.

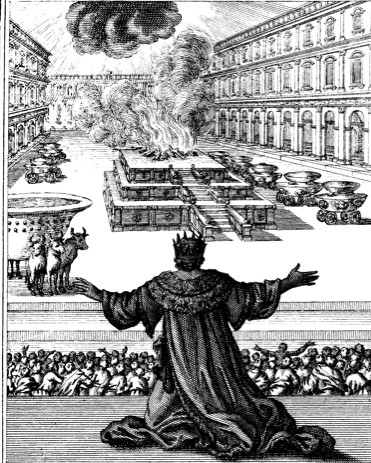

Unlike the author(s) of Kings, the Chronicler focusses on the reigns of David and Solomon, deliberately omitting the negative elements of their characters and reigns. There is no mention of the wars with the house of Saul, the Bathsheba episode, the filial rebellions during David’s reign, and Solomon’s apostasy late in life. Clearly David and Solomon are idealized monarchs, archetypes of a future ruler whose reign would bring the whole of history to its proper culmination. The Chronicler looks ahead to the ultimate fulfilment of God’s kingdom by portraying David and Solomon as concerned primarily with the nation’s liturgical life, including the building of the temple, housing the Ark of the Covenant, and organizing cantors and musicians. Israel is a worshipping nation first and foremost, paying homage to the God who called them into a covenant relationship with himself. Everything else is ancillary.

So hopeful is the Chronicler that he envisions a time when the bitter cleavage between the northern and southern kingdoms will be healed and all Israel will be reunited under the future Messiah (2 Chronicles 30), as prefigured by Hezekiah’s reforms.

Finally, the books end on a hopeful note. While 2 Kings ends with the deposed Judahite king Jehoiachin dining at the table of the Babylonian ruler Evil-merodach, 2 Chronicles ends with Persian King Cyrus allowing the exiles to return to the promised land (2 Chronicles 36:22-23), a passage repeated at the beginning of Ezra (1:1-3).

So, no, the two books of Chronicles are not just needless repetition of Samuel and Kings. They place that same history in messianic perspective, giving the reader a foretaste of the final consummation of Israel’s hope—the coming of “great David’s greater Son,” Jesus Christ.