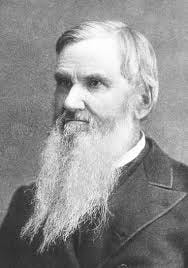

R.L. Dabney on Public Prayer

R.L. Dabney has a wonderful chapter on public prayer at the end of his book Evangelical Eloquence. Public prayer is not something I was taught formally in seminary nor informally watching my ministers growing up. Like the public reading of Scripture it is ignored. Samuel Miller also wrote a book on public prayer in 1849. But since the 1800’s the importance of prayer in the pulpit has been forgotten.

Dabney begins by saying, “I deem that the minister is as much bound to prepare himself for praying in public as for preaching. The negligence with which many preachers leave their prayer to accident [chance], while they lay out all their strength on their sermons, is most painfully suggestive of unbelief toward God and indifference to the edification of their brethren.” For many years little thought went into my public prayers. What did I teach my congregation about approaching God when I prayed in a sloppy, poorly thought out manner? He goes on to say, “The many blemishes which we hear in public prayers are to be traced to two sources: first, deficient piety, and second, deficient preparation.” We are not holy enough, near enough to God in our daily lives and we do not think about our prayers beforehand.

Then Dabney gives six things we should remember about public prayer. There is a lot of wisdom in this list.

1. The grace of prayer is to be secured only by a life of personal and private devotion. He who carries a cold heart into the pulpit betrays it not only to God, whose detection of it is inevitable, but almost surely to the hearers also.

2. The pastor should remember that he is praying on behalf of the people, therefore his language should be simple, his petitions corporate, not private and he should make sure he is praying, not preaching…the language of prayer must be wholly unambitious, unaffected, and simple…not such as is proper from a teacher to a congregation, but just such as is appropriate for an accepted sinner speaking to his God.

3. The leader of the church’s prayers shall present distinct and definite petitions, and these not too numerous….The leader of prayer should therefore speak as one who has an errand at the throne, a point to press to God. He should eschew loose generalities of petition, and all that stream of indefinite, goodish talk with which so many prayers are filled, which really expresses nothing save a slumbering faith and a heart void of desire.

4. He who leads the devotions of others must study appropriateness of matter. He should ask himself what would be uppermost in the hearts of Christians at that time.

5. The language of prayer should be well-ordered and considerate. He who speaks to the Searcher of hearts should beware how he indulges any exaggeration of words, lest his tongue should be found to have outrun his mind and to have “offered the sacrifice of fools.”

6. Above all should the minister enrich his prayers with the language of Scripture. Besides its inimitable beauty and simplicity, it is hallowed and sweet to every pious heart by a thousand associations. It satisfies the tastes of all; its use effectually protects us against improprieties; it was doubtless given by the Holy Spirit to be a model for our devotions.

The post R.L. Dabney on Public Prayer appeared first on Kuyperian Commentary.