E. E. Cummings

maybe god

is a child

‘s hand)very carefully

bring

-ing

to you and to

me(and quite with

out crushing)the

papery weightless diminutive

world

with a hole in

it out

of which demons with wings would be streaming if

something had(maybe they couldn’t

agree)not happened(and floating-

ly int

o

E. E. Cummings, Poem 54 from XAIPE

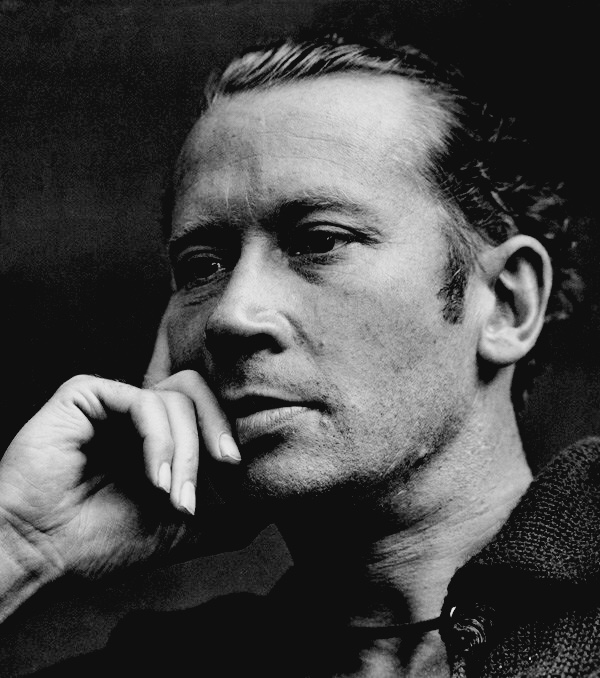

This past October marked the 123rd birthday of the American poet, painter, and writer Edward Estlin Cummings (10/14/1894-09/03/1962). The poetry of E. E. Cummings is quite a different thing. His use of syntax, to say nothing of his typographical hijinx, is difficult and off-putting, but there is a reason to what appears to be madness. By disrupting the sentence, or sometimes even a word itself, with parentheticals and line breaks, Cummings forces the reader to slow down, to ponder how the new information changes the meaning.

The opening lines have several startling elements:

1) “maybe god”: the adverb of uncertainty and the lower case spelling might lead us to believe that we’re hearing a skeptic’s musings until we encounter

2) “is a child” leading us in two separate directions, the one leading to impiety (God is a baby/spoiled/incompetent) the other leads to the question of incarnation, but this

3) is nullified by the beginning of the third line: “ ‘s hand” which is a poetically original idea that drives out anything from skepticism, blasphemy, and Christmastide.

Having wiped clean the slate Cummings builds his case. God brings us the world (and notice that the line breaks slowing us down. See how careful:

very carefully

bring

-ing

to you and to

me(and quite with

out crushing)the

papery weightless diminutive

world

The world is called “papery weightless diminutive” which is closer to how we think of God as spirit, weightless, ephemeral, ghostly; whereas we are flesh, we are solid. Cummings inverts out thoughts, showing the fragility of the world.

We need not bristle at his making God a child, there is no malice in the image. Had Cummings read G. K. Chesterton he would’ve certainly highlighted his well known quote on God’s love of repetition, causing the sun to rise each day and making sunflowers all alike, “It may be that He has the eternal appetite of infancy: for we have grown old and our Father has been forever young.”

There is a problem with this world: there’s a hole in the world “out/ of which demons with wings would be streaming”. The demons do not stream out of this hole because of some mysterious event that at first seems left out, but with closer inspection we can discover it. Before we go on, however, let us recall how the short lines slowed down our reading, but here the effect is reversed. The extended line gives us a picture of just how quick the flood of demons would be:

world

with a hole in

it out

of which demons with wings would be streaming if

Rather than chopping up the sentence to slow us down, the extended line speeds things up, giving us a sense of danger as well as showing us just how quick the flow of demons would be. That “if” hangs out like a question, driving us to the answer, an answer that continues to be delayed by speculation about the cause of the problem, “(maybe they couldn’t/ agree)”. This observation, being so basic, causes us to realize that the speaker of this poem isn’t a skeptic (as we first thought) or a blasphemer (as we later thought), but the speaker is a child. We, through the reader, have become a child; a conversion has occurred and we know are in the image of God. The poem ends:

(and floating-

ly int

o

The disjointed nature of this clause causes us to back up. We notice the parenthetical without end and retrace our steps until we find the antecedent: “maybe god// is a child/ ‘s hand)”. We realize that the body of the poem is an interjection and the sentence is split in the middle. Thus reunited the line reads “maybe god is a child’s hand and floatingly into” revealing the event that healed the world. God put His hand into history, into the world, and demons no longer stream out. Note the final “o” pictures the world, the hole, as well as the diminution. Rather than a sense of superiority over this childlike God we are identified with Him and, more than that, the poem shows that even a child can see the glory of salvation and the gift of the world.

*Remy Wilkins is a professor at Geneva Academy of Monroe, a poet and novelist. His first novel Strays (CanonPress 2017) is a YA adventure also available through Amazon. This post originally appeared on his blog during Advent of 2007. It is here updated and republished by permission of the author