By Contributing Scholar, Timothy LeCroy

Introduction

There does not seem to have been any distinctive everyday dress for Christian pastors up until the 6th century or so. Clergy simply wore what was common, yet muted, modest, and tasteful, in keeping with their office. In time, however, the dress of pastors remained rather conservative, as it is wont to do, while the dress of lay people changed more rapidly. The result was that the dress of Christian pastors became distinct from the laity and thus that clothing began to be invested (no pun intended) with meaning.

Skipping ahead, due to the increasing acceptance of lay scholars in the new universities, the Fourth Lateran council (1215) mandated a distinctive dress for clergy so that they could be distinguished when about town. This attire became known as the vestis talaris or the cassock. Lay academics would wear an open front robe with a lirripium or hood. It is interesting to note that both modern day academic and clerical garb stems from the same Medieval origin.

Councils of the Roman Catholic church after the time of the Reformation stipulated that the common everyday attire for priests should be the cassock. Up until the middle of the 20th century, this was the common street clothes attire for Roman Catholic priests. The origin of the clerical collar does not stem from the attire of Roman priests. Its genesis is of Protestant origin.

The Origin of Reformed Clerical Dress

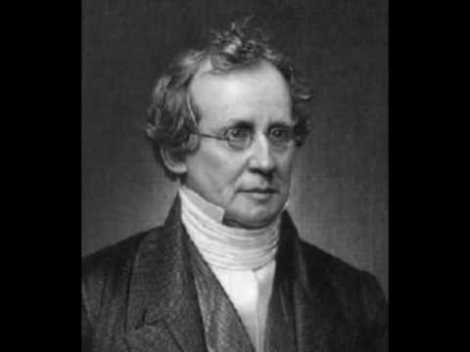

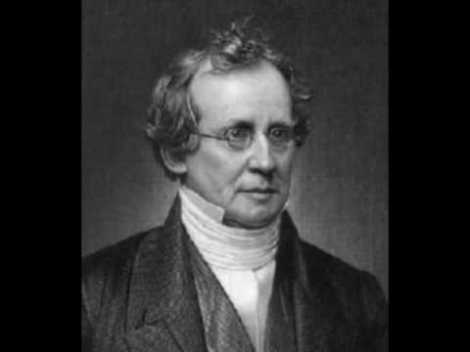

In the time of the Reformation, many of the Reformed wanted to distance themselves from what was perceived as Roman clerical attire. Thus many of the clergy took up the attire of academics in their daily dress or wore no distinctive clothing whatsoever. Yet over time the desire for the clergy to wear a distinctive uniform returned to the Reformed churches. What they began to do, beginning in the 17th century as far as I can tell, is to begin to wear a neck scarf, called a cravat, tied around the neck to resemble a yoke. Thus common dignified attire was worn by the pastor, supplementing it with this clerical cravat. This style can be seen in many of our famous Reformed divines, one of the more famous of whom being Charles Hodge.

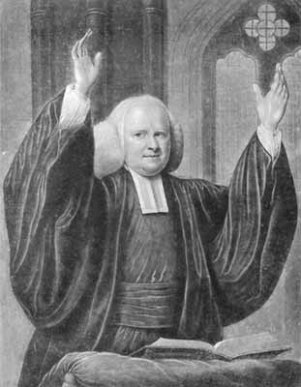

When Reformed pastors would enter the pulpit, they would add what is known as a “preaching tab” or “neck band” to their clerical dress. This type of dress is nearly ubiquitous among 17th and 18th century Reformed pastors. Here are a few examples:

In the following picture we see more clearly the use of both the clerical cravat and the inserted preaching tabs by one Thomas Chalmers.

The reader will note that the men depicted here were of great eminence as Reformed pastors and theologians. They are all well known for their commitment to Reformed theology and biblical teaching and practice. These are not obscure men who sported clerical attire.

One might ask whether this sort of attire was universal among the Reformed. The answer is, no. Upon perusing several portraits included in the Presbyterian Encyclopedia of 1880, published by Presbyterian Publishing Co. of Philadelphia, I found that there was diversity of clerical attire chosen by Presbyterian pastors of the 19th century. Some wore clerical cravats. Some wore what looks like a modern rabat with a collarette (a black vest which closes at the top with a bit of white collar revealed all around). Others wore bow ties or neck ties. The conclusion to be drawn is that in the Presbyterian tradition, there has been diversity of clerical dress without any type enforced over the other.

Another objection that might be raised is whether or not this neck band or cravat, such as we see Charles Hodge wearing, was in any way distinctive clerical garb. Several 19thcentury sources reveal that these cravats were, in fact, considered distinctive clerical garb. The following quote is from a 19th century source called The Domestic Annals of Scotland, Volume 3:

In the austerity of feeling which reigned through the Presbyterian Church on its reestablishment there had been but little disposition to assume a clerical uniform or any peculiar pulpit vestments. It is reported that when the noble commissioner of one of the first General Assemblies was found fault with by the brethren for wearing a scarlet cloak he told them he thought it as indecent for them to appear in gray cloaks and cravats. When Mr. Calamy visited Scotland in 1709 he was surprised to find the clergy generally preaching in neckcloths and coloured cloaks. We find at the date here marginally noted that the synod of Dumfries was anxious to see a reform in these respects. The synod – so runs their record – “considering that it’s a thing very decent and suitable so it hath been the practice of ministers in this kirk formerly to wear black gowns in the pulpit and for ordinary to make use of bands do therefore by their act recommend it to all their brethren within their bounds to keep up that custome and to study gravitie in their apparel and every manner of way.”

Here we see several members of the 18th c. Church of Scotland (Presbyterian) having their hackles raised over some ostentatious clergymen wearing scarlet cloaks and cravats. Later they hold a Synod where they decide that they ought to wear black gowns and to make use of neck bands. This paragraph shows us two things: the wearing of cravats was considered to be distinctive clerical garb, and the synod of the kirk decided ultimately that modest use of neckbands was permitted. (There are many more such examples in 19th century sources which can easily be researched on Google Books. I invite the reader to see for himself.) Thus when we see all manner of 17th-19th century Reformed pastors sporting preaching tabs, neck bands, and cravats, we should interpret them to be intentionally sporting distinctive clerical garb. We should also gather that the author of these annals, one Robert Chambers, included this anecdote in his work in order to promote the modest use of bands and clerical garb in his day.

The last bit of history to cover regards the origin of the modern clerical collar. According to several sources, including one cited by the Banner of Truth website (no Romanizing group), the modern clerical collar was invented by a Presbyterian. In the mid 19th century heavily starched detachable collars were in great fashion. This can been seen up through the early part of the 20th century if one has watched any period television shows or movies. If we observe the collar worn by Charles Hodge we can see that at first these collars were not folded down as they are today, but left straight up.

Yet in the mid to late 19th century it became the fashion of the day to turn these collars down. You and I still wear a turned down collar. The origin of the modern clerical collar is simply then to turn or fold the collar down over the clerical cravat, leaving the white cloth exposed in the middle. According to the Glasgow Herald of December 6,1894, the folded down detachable clerical collar was invented by the Rev Dr Donald McLeod, a Presbyterian minister in the Church of Scotland. According to the book Clerical Dress and Insignia of the Roman Catholic Church, “the collar was nothing else than the shirt collar turned down over the cleric’s everyday common dress in compliance with a fashion that began toward the end of the sixteenth century. For when the laity began to turn down their collars, the clergy also took up the mode.”

Yet two questions arise: how did the clerical collar then fall out of use among Presbyterians and how did it come to be so associated with Roman Catholic priests? The answer is that up until the mid 20th century the prescribed dress for all Roman Catholic priests was the cassock, a full length clerical gown. Yet during the 20th century it became custom for Roman Catholic priests to wear a black suit with a black shirt and clerical collar, which collar they appropriated from Protestant use. Owing to the large number of Roman Catholic priests in some areas, and due to the fact that some sort of everyday clerical dress was mandated for all priests at all times when outside their living quarters, the clerical collar became to be associated more with the Roman Catholic Church than with the Protestant churches. It stands to reason that once again a desire to create distance between the Reformed and Roman Catholics and the increasing desire throughout the 20th century for ministers to dress in more informal ways has led to the fact that barely any Reformed pastor wears any distinctive clerical dress these days, though plenty of examples show that our eminent forbearers desired to do so.

Sources

The New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2nd Edition, 2003

The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation, 1996

The Presbyterian Encyclopedia, Alfred Nevin, 1880

Wikipedia: Clerical Collar

Wikipedia: Bands (neck wear)

Wikipedia: Clerical Clothing

Clerical dress and insignia of the Roman Catholic Church, Henry McCloud, 1948

Domestic Annals of Scotland, From the Revolution to the Rebellion of 1745, Robert Chambers, 1861, pp. 147-148.

Google Images

Google Books

Wikimedia Commons

Ken Collins’ Website – Vestments Glossary

Banner of Truth Website

Pastor Garrett Craw’s Blog

Dr. Timothy LeCroy is a Special Contributing Scholar to the Kuyperian Commentary and is the Pastor of Christ Our King Presbyterian Church in Columbia, MO.

This post originally appeared on Dr. LeCroy’s blog, Vita pastoralis.<>

There is good scholarship which shows that clerical garb began with Constantine. The Christians were highly regarded for rendering sound judgment in a timely manner, so much so that “pagans” preferred Christian judges over those of the Roman state where cases remained in limbo for decades. With Christianity as the official state religion, in addition to providing elaborate public facilities for worship, Constantine also decorated the new Christian judges to look state officials.

As for me, my church is a large log cabin in Montana and when I give a sermon I wear Montana formal… blue jeans and a clean plaid shirt.

D. B.

Considering that the first apostles (“clerics” 0 of the New Testament Church were fishermen, doctors, etc….. I highly doubt that any special attire was worn by those that accompanied our Lord. Therefore special attire is unnecessary and a tradition of men. If someone wants to wear their clerical collar, feel free to do so, but it is no big deal if the pastors of our day dress as the “common” people of our day. They are in good company with the people that Jesus chose as his apostles “common” people of his day.

Dear sir/ma’am,

Thank you for your contribution. Please feel free to comment and look through our many articles.

Liberty,

Thanks for your interaction. I have a few points that I want to put forth regarding what you said. First of all, yours is an argument from silence. You highly doubt because of your presuppositions. But you presuppositions are exactly what I am challenging, specifically the notion that it is good and right for pastors to wear a uniform. You do not see any possibility of the apostles wearing a uniform because you presuppose that it is a bad or unnecessary thing. Am I wrong?

There is evidence in the NT that there was some sort of distinctive dress for pastors. Jesus’ seamless tunic is seen by many to be a priestly garment. Paul’s “cloak” in 1 Timothy 4:13 is seen by some as a pastoral garment. Furthermore, all through the NT men (or angels, but a lot of the texts just say men) show up proclaiming authoritative things while wearing dazzling white robes.

Secondly, if you argue only from the NT the evidence may be scant, but we find ample direction from the OT that priests wore distinctive garb.

Thirdly, to your main point about the traditions of men. Yes, I agree that we can’t find anyone in the bible wearing a collar. Neither can we find them wearing a suit and tie. Or a printed t-shirt and blue jeans. So anything we might say about the prudence of ministerial dress is necessarily the opinions and traditions of men, as you say. But who says we should never listen to the opinions and traditions of men? I find it inescapably biblical to listen to wise men and women who have gone before us.

Now if your point is that I should not assert that ministers must wear a collar in their everyday ministry, your point is well taken. But that was not the purpose of my post. I was not asserting that you must, but that I can, and that when I do, I stand in the line of a great many venerable pastors and teachers. But when you say that it is “no big deal,” I can’t say that I agree. Our dress communicates a great deal about us. What would you like police officers to wear? Doctors? Firemen? Judges? Certainly there is not a moral issue if a judge shows up to court in flip flops and shorts, but will he be taken seriously? Will the force of his ministry be muted because of his appearance?

You tell me.

I do not have any problem with a pastor choosing to use a collar or a robe. My own pastor does so. Nor though, do I have any problem with a suit and tie, a nice shirt and jeans/slacks etc…..

However, none of the disciples or original 12 apostles were priests. Jesus chose to call ordinary people that wore ordinary garments. Surely if those who were not of the priesthood started wearing special priestly robes, there would have been a huge stir amongst the Jews. The priesthood of the OT is no longer. The temple system is no longer needed because it was fulfilled in Jesus Christ’s work on the cross. Jesus is our high priest and all believers are priests.

All traditions are not bad, but Jesus did warn us about following traditions, so he apparently thought it to be a problem. “Beware lest anyone rob you through philosophy and vain deceit, according to the tradition of men, according to the elements of the world, and not according to Christ.” Colossians 2:8, MKJV. “And the Pharisees and some of the scribes came together to Him, having come from Jerusalem. And when they saw some of His disciples eating loaves with unclean hands, that is with unwashed hands, they found fault. For the Pharisees and all the Jews do not eat unless they immerse their hands with the fist, holding the tradition of the elders. And coming from the market, they do not eat without immersing, and there are many other things which they have received to hold, the dippings of cups and pots, and of copper vessels, and of tables. Then the Pharisees and scribes asked Him, Why do your disciples not walk according to the tradition of the elders, but eat loaves with unwashed hands? But He answered and said to them, Well has Isaiah prophesied of you hypocrites, as it is written, “This people honors Me with their lips, but their heart is far from Me. However, they worship Me in vain, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men.” For laying aside the commandment of God, you hold the tradition of men, the dippings of pots and cups. And many other such things you do. And He said to them, Do you do well to set aside the commandment of God, so that you may keep your own tradition?” Mark 7:1-9, MKJV.

So, I think we need to be very careful before we look to traditions, just because godly Christians of the past did them, to determine what is correct for us. IMHO, the reason why so many choose to leave some of our reformed denominations for Eastern Orthodoxy or Roman Catholicism is due to the importance made of following traditions and not being willing to state that those two groups are not biblical Churches.

Actually, I would argue that the reason why so many are converting to Romanism or Eastern Orthodoxy is the exact opposite: we have allowed those churches to define the historical narrative on their terms. There is no reason to fear history or tradition when they are understood properly. Otherwise the church has to be reinvented anew in every generation. Of course, we must interact critically with tradition, but we also should give it the due weight it deserves and only abandon those things that are expressly un-biblical.

To your other point, the priesthood of all believers doesn’t preclude the role of human mediators. It has never meant that. Not to Luther, Calvin, or anyone else until the evil of modernism that has plagued our ecclesiastical psyche over the last 100 years. We are actually coming out of the era of Enlightenment modernism now, and that is a good thing. Rationalism is a disease.

“For God is one, and there is one Mediator between God and man, the Man Christ Jesus,” 1 Timothy 2:5, MKJV.

And tell me, where did you get that scripture verse? Did you translate it yourself from the original Greek? Did you discover a 1st century autograph of Paul’s letter to Timothy and transcribe it and translate it yourself? Or did someone, or rather a very large group of someones, copy that text, preserve that text, transcribe and translate that text, and deliver that text to you as you have now quoted it to me. Moreover, I’m guessing you did not even type that text from your print bible but simply copy and pasted it over from either a software package or an on-line source.

My point is that all those points in between are human mediators. All those hundreds and thousands of people that did that work of preserving the scripture were priests to you. You would not have a faith without their mediation and priesthood to you.

Do you not listen to the word read and preached? Do you not have someone deliver the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper to you? Or are you a church of one? All those who read to you, who preach to you, and who deliver the sacraments to you are priests and mediators to you.

The priesthood of all believers doesn’t mean that it’s just you and Jesus. It means that every believer is a priest and has the role of mediating the faith to other people. It is corporate and not individualistic.

In context, that verse that you quoted at me means every believer can pray directly to God the Father through Jesus Christ. It does not give you or me or anyone else the license to forsake all human mediators of the faith.

[…] may be uncomfortable with a clerical collar because they think it is Roman Catholic. Actually, a Presbyterian minister first introduced the collar, though there appear to have been precursors. Portraits of Reformed ministers from the mid-1700s […]