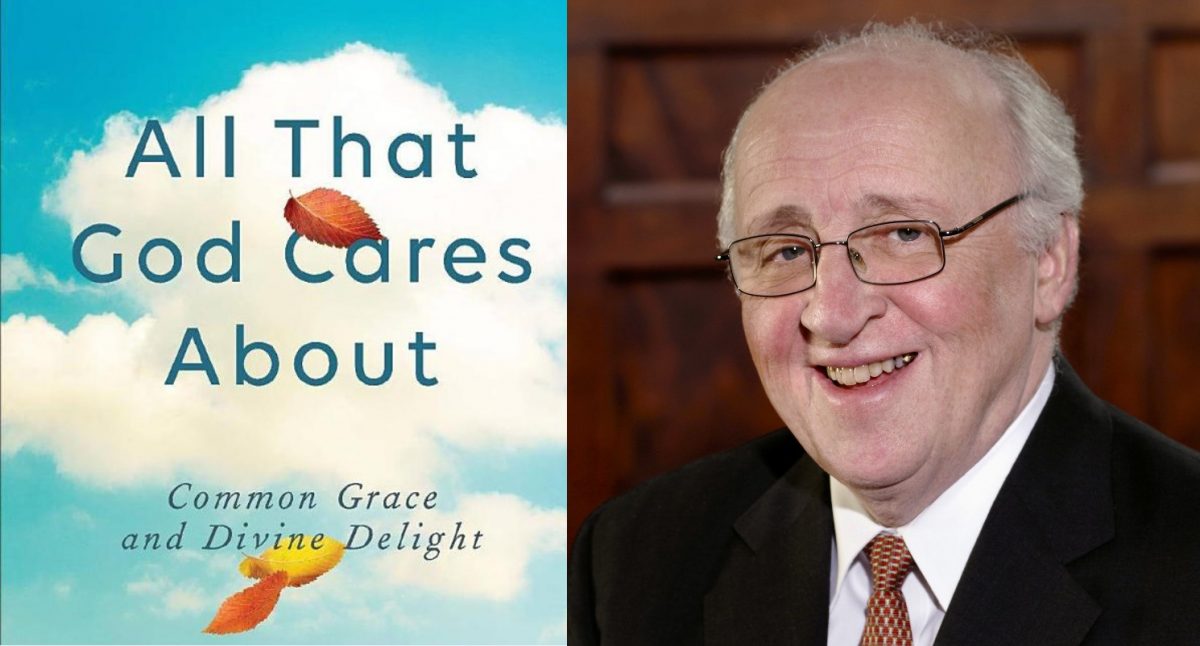

Richard Mouw is a big name in Kuyperian circles. He regularly writes about neo-Calvinism and Kuyper’s vision of Common Grace. His latest book, All that God Cares About (available June 16, 2020), continues that work. I will admit that this is my first look at Mouw’s work so I am behind in the conversation but I think it is worth jumping in here since Mouw says that this book is an update on his previous work on common grace.

For those new to the discussion, common grace is the term theologians use to describe the work that God does in restraining unregenerate men from doing evil continually and instead enables them to do limited good in the world. This teaching comes from key passages in the Bible as well as John Calvin and other reformers. It is closely related to the doctrine of total depravity: fallen man is dead in his sin and is incapable of redemption apart from God quickening him. In teaching total depravity, Calvin and others acknowledge the Bible’s teaching that unregenerate Man is not absolutely evil in all actions but in fact often does real positive good in the world.

In considering common grace, the primary question Mouw considers is how God can both bless non-Christians with artistic skills and also allow them to go to Hell. At one point, Mouw points to ancient Chinese pottery and asks: “What does God think of those pots and vases? I don’t think the production of these works of art is explainable simply in terms of the providential restraint of sin. My sense is that the Lord took delight in the talents of the artists themselves in crafting this pottery and wants us to delight in them as well” (Kindle Location 905). In this example, Mouw is pushing back on the frequent description of common grace as merely a restraint on evildoers and instead Mouw suggests that in some way God actually delights in these gifts that he gives to non-Christians.

I appreciate much of Mouw’s discussion in this book and it was edifying to read about other theologians who have talked about this issue: Cornelius VanTil, Klaas Schilder, and Herman Hoeksema. I do have some concerns about this book but I will discuss one key appreciation first.

Mouw Against Universalism

In discussions on common grace, it is easy to emphasize this grace so much that common grace becomes salvific grace. Mouw is aware of this temptation and error and he is clear that he does not hold or teach that error.

He says, “The “grace is everywhere” line should not be affirmed, though, without maintaining a clear focus on the marvelous saving grace that is not everywhere” (loc 1216). And also: “The antithesis is real, and neo-Calvinism cannot flourish without staying focused on that reality (loc 1216). Mouw’s emphasis on the antithesis is key and important.

Later he says, “So I must say this in a straightforward manner: I am not a universalist. Indeed, unlike some of my evangelical friends, who say that while they cannot read the Bible as endorsing universalism they do hope it turns out to be true, I am not even tempted by universalism” (loc 2015).

This distinct and clear discussion is helpful to see and this is important in a discussion on common grace.

Some Concerns

One key concern I have is how Mouw handles the book The Catholic Imagination by Andrew Greeley. Mouw writes, “Those who read Greeley’s fiction will not be surprised to find that for him ‘the Catholic imagination’ features a vibrant celebration of our lives as human creatures” (loc 285).

Mouw then recounts how Greeley cites an example from a movie by Lars von Trier called Breaking the Waves. The movie is about a woman named Bess who is married to Jan and lives in a “dour” Scottish Presbyterian community where the congregation is so suspicious of sacraments that they remove the bells from the bell tower of the church. Greeley explains that Bess experiences powerful pleasure in her sexual love with her husband and tries to thank God for that pleasure but ends up thinking of Him as a grudging Calvinist (loc 288).

Mouw holds up Greeley’s discussion as a key critique of Calvinism and art, but this idea is troubling in a couple of key ways.

First, the movie that Greeley references, Breaking the Waves, is a terribly immoral movie. I have not seen it but the description on Wikipedia is enough to make me roll my eyes. Here are some key points from the movie. Jan, the husband, is in an accident and no longer able to perform sexually so he tells Bess to find another lover. Bess eventually gives in, thinking it will heal her husband, and so she sleeps with a number of men off the street. She is eventually excommunicated from her church and she dies being gang raped by some sailors.

Mouw says nothing about how ludicrous the plot is nor how terribly immoral the movie is, which is rather surprising. He then seems to uphold Greeley as having an insightful eye about art and Calvinism. If Greeley thinks Breaking the Waves is good art, I have serious doubts if he would be able to say anything helpful about Calvinism and art.

Mouw offers this quote from Greeley: “the classic works of Catholic theologians and artists tend to emphasize the presence of God in the world, while the classic works of Protestant theologians tend to emphasize the absence of God from the world. The Catholic writers stress the nearness of God to His creation, the Protestant writers the distance between God and His creation; the Protestants emphasize the risk of superstition and idolatry, the Catholics the dangers of a creation in which God is only marginally present” (loc 296).

Mouw does push back on this claim a little but it would be more helpful for him to offer some specific counter examples here. He is a little too abstract on this discussion so it is hard to see where he disagrees with Greeley.

While some claim that Protestants are bad at art or are not able to employ a sacramental imagination, I am not convinced of this historically. I agree that there is a weakness in recent Protestant art, not counting Marilynne Robinson, but the reality is that Protestants have been the dominant artists for the last 500 years: Shakespeare, Milton, Bach, Rembrandt, Lewis, and others. These are all great examples of how Protestants use art to reveal God’s nature and interest in the world. It seems that Mouw should have pushed back harder on Greeley.

Reading the Story

The final thought I have on the book is that Mouw approaches the issue of common grace and art from a position that is too abstract. That is, he doesn’t look at non-Christian artists from the perspective of a story.

At one point, Mouw talks about Thomas Carlyle and his work Sartor Resartus. Mouw says, “And now, as then, I feel no need to reclaim those sentences from Carlyle. Yes, he was in a state of unbelief when he wrote them, but knowing that does not make me see these sentences as his “unlawful possession.” I don’t want to “seize” them from him. I want him to “keep” them. They are an expression of his gifts. So, like Doc Jo, I thank the Lord for Thomas Carlyle himself” (loc 636).

In this example, Mouw is asking how we, as Christians, can appreciate this work on the one hand while also recognizing that Carlyle is condemned to Hell as a non-Christian.

I think it would help Mouw in this discussion to take the long view of Carlyle’s life. How did he end up? It seems that while Carlyle was a good writer and rather witty, his marriage was rather terrible. Samuel Butler is reported to have said, “It was very good of God to let Carlyle and Mrs Carlyle marry one another, and so make only two people miserable and not four.” Evidence suggests that Carlyle and his wife had a long correspondence that was harsh and full of anger. From this, we see that the gift of writing actually came back on Carlyle’s head.

This gives perspective on how God’s common grace works in a person’s life. As a non-Christian continues through life he becomes hardened against the grace of God, and like Carlyle, ends life in a miserable place.

Another way to get at this point is to say that Hell is not a destination so much as a state of being which sinners become. While God blessed Carlyle with the grace to write well, Carlyle rejected the giver of the gift and this led him to a dark and lonely place. In this way the gift he had became his curse: he could write well to the public but he could not write a letter to his wife.

Looking at the work of non-Christians from this larger perspective would help Mouw as he works to understand God’s common grace to unbelievers. While God’s common grace to them can be seen in specific works, non-Christians, apart from God, are using God’s common grace to build Hell for themselves. The story of the non-Christian’s life helps us to both appreciate the non-Christian’s work and at the same time recognize that where he ended up was under the judgment of God.

but the reality is that Protestants have been the dominant artists for the last 500 years: Shakespeare, Milton, Bach, Rembrandt, Lewis, and others.

Umm, “the” dominant artists? Sure, the superiority of the Catholic imagination and sacramental vision, and related claims, are often an overstatement but surely this is just as bad of an overstatement. Protestants “have been among the dominant artists” would be a much better way to state the matter. And Catholics can claim in the post-Trent era the artistic genius of Johannes Vermeer, Peter Paul Rubens, Caravaggio, et al., among painters; Pugin in architecture; Corelli, Mozart, and innumerable composers; Tolkien and O’Connor in literature.