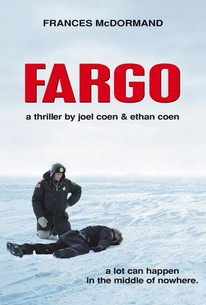

A while ago I wrote a post about strong female characters in movies comparing Wonder Woman and Elastigirl. A reader of the Kuyperian blog, Anthony, responded and asked if I had seen Fargo. He suggested Margie as an interesting female character. So I watched the movie over Christmas break. Here are some of my thoughts on the movie in general and on the question of Margie as a strong female character.

A while ago I wrote a post about strong female characters in movies comparing Wonder Woman and Elastigirl. A reader of the Kuyperian blog, Anthony, responded and asked if I had seen Fargo. He suggested Margie as an interesting female character. So I watched the movie over Christmas break. Here are some of my thoughts on the movie in general and on the question of Margie as a strong female character.

Whenever I watch a Coen brothers’ film, I always feel like I am walking into the book of Judges. The world is a little tilted and the hero is always a surprise because he or she is never who you thought it was going to be. Fargo is like this in many ways. The story starts with a strange and dark premise that is also a bit humorous: a man wants two thugs to kidnap his wife and hold her for ransom so he can extort money out of his wealthy father-in-law who will pay the ransom.

This setup presents the sharp reality that even a family man can embrace terrible darkness. But the humor of this beginning also suggests the deeper justice at work in the story. While evil is a dreadful force to be reckoned with in the world, it is never out of control. There is always a deeper truth at work which is controlling everything so that even the darkness serves the purpose of the comical ending.

On the technical side of things, the Coen brothers are masters of creating a specific region. As I watched the movie, I thought of a comment from Flannery O’Conner: “Art requires a delicate adjustment of the outer and inner worlds in such a way that, without changing their nature, they can be seen through each other. To know oneself is to know one’s region” (The Fiction Writer and His Country). The Coens ensure that the location of the story, dark, cold North Dakota, becomes a character in the story. The cold biting edge of the world is inside most characters in the story. It is only Margie and her husband Norm who do not give into this cold world. They share a joy and love that pushes back against the cold.

Into this dense setting, the Coens place characters who are equally thick. No one is extra. Even small side characters, like the old friend from high school, are full real characters. This also grounds the story in a deep reality.

Before moving onto the meaning of the story, I do have to acknowledge one huge flaw in the storytelling abilities of the Coens: the two sex scenes. It is really too bad that such a rich story with such rich characters falls into this kind of cartoony story telling. A sure sign that a story teller has fallen asleep at the wheel is a sex scene. It takes no brains or talent to pull one off. The reality is that the movie would have been a far better story if the Coens had left these things as suggested actions off stage. If they had done that, it would indicate that they trust their audience to put the pieces together and it would also add greater depth to the story. I am not against a character going to a prostitute; I am against a director trying to use sex to sell his story. If he wants to do that, he should go join the porn industry.

Now to the meaning of the story.

While the story is set deep in reality, the story unfolds as a parable about the nature of evil and true justice. The chief of police, who is a pregnant woman named Margie, is the embodiment of justice. The Coens are working with the traditional symbol of Lady Justice as a woman who is blind. While we often interpret blind Justice as a symbol of being unbiased in a decision, it is also important to point out that the blindfold is also an obstacle to her work. Blindfolded Justice is not going to get very far in her investigation. The Coens pick up this idea of encumbered Justice and instead give us a picture of Lady Justice who is pregnant.

This particular detail about Margie is the key to understanding the nature of justice in the story. True justice is not a quick, swift act of vengeance. It is not a simple solution to a basic addition problem. True justice is stranger and more mysterious than that. This pregnant, waddling woman is a picture of how justice often seems to work: it walks slowly, it has a funny accent, and it gets morning sickness. But even with these limitations Justice is made for holding and creating life. And in the end, even though justice might be slow, it will always right the wrong. And this is true because evil can’t ever win. So while it seems like evil is faster and more cunning than a pregnant woman, evil will eventually undo itself. In the end, evil is so evil that it will even kill itself.

A friend suggested that this story is a Christmas story which I think is insightful. The name of the pregnant woman, Margie, has echoes of Mary in it. You also have a story of two families. In the first family, the husband is evil and his actions are set to destroy his family. In the other family, the husband is loving and cares deeply for his family. He gets up early so his pregnant wife can have a decent breakfast. And this is a story of a woman being the key component in the overthrowing of evil.

In this film, the Coens make Margie a true woman. She is not a cardboard cutout. She doesn’t have any super powers. She is intelligent, although you might not realize that from how she talks. She has to deal with real people. At one point, she even misjudges the character of an old friend from high school. In these ways, we see the comical nature of justice which works through strange means in ways that are almost hidden to our eyes but in the end Lady Justice, even if she is pregnant, always gets the bad guys.

I’d argue that the sex scenes are not “selling” the story; they’re “telling” the story. Notice who participated in them: the bad guys. The sex is not romantic or sensual… it’s ugly; it’s mechanical. Contrast that with Marge and her husband. They share a bed and enjoy each other’s company. You don’t see their sex scene, only the result of it: new life.

Similarly, the language also conveys this contrast. The bad guys use the “f” word about 150 times. Marge never cusses.

In the middle you have Jerry – a man who appears to be on the Marge side of the equation, but is actually on the other (or is moving in that direction). He doesn’t cuss either (except when he’s ultimately confronted by Marge and his back is against the wall), but his son uses the “f” word. Similarly, his marriage has the appearance of Marge and her husband, but he is exploiting his wife – willing to leave her alone with strange criminals.

If the sex/language (and violence for that matter – again, contrast the use of force between the “dark” and “light” sides) were meant to sell the movie, they’d be used much differently.

Thanks for the thoughts, Brian. I posted this on Facebook also but I will share it here also. My point is that the Coens could have told the story without showing everything in the sex scenes. If the viewer can’t figure out that the two bad guys are bad without a dirty sex scene then I think the story tellers have failed. But we know those two guys are bad right away. The Coens show us that really well in other ways. I also like your point about comparing and contrasting between the good and the bad. You can still have all that without an explicit sex scene. My main point is that the sex scenes are unneeded.