God’s Divided People: Biblical Lessons for the Church

The recent observance of the 502nd anniversary of the Protestant Reformation should once again prompt us to reflect on the unity of God’s church amidst so many divisions. Christians everywhere can point to Jesus’ high priestly prayer recorded in John’s gospel: “that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you” (John 17:21), yet wonder why this cannot be a present reality. It’s not just that churches are organizationally distinct but that they do not enjoy full communion with each other, erecting barriers preventing their members from recognizing outsiders as brothers and sisters in Christ.

Of course, some church bodies deny that God’s church is divided at all. The Roman Catholic Church claims to be the one holy catholic and apostolic church founded by Jesus nearly 2,000 years ago. Other communions are officially in schism from this one true church, and their members constitute at most separated brethren in imperfect communion with Rome. The Orthodox Churches, while organizationally more pluriform, return the favour, claiming that Rome, along with every other ecclesiastical body, is outside the one true church, embodied in global Orthodoxy.

Many Protestants, especially after the 16th century, have taken a more relaxed attitude to church unity, arguing that the invisible church is united in the one Saviour Jesus Christ—a unity transcending the institutional divisions within the visible church. Nearly four decades ago, I heard from the pulpit an anglo-catholic bishop of the Episcopal Church who expressed the conviction that the church contains three branches: Catholic, Orthodox and Anglican. He was evidently pleased to be part of the third branch, yet his “branch theory” was and remains exclusive to his wing of the Anglican communion. Genuine Catholics and Orthodox do not find it credible. Nor do the more Cranmerian Reformed Anglicans.

In the first half of the last century, many larger protestant churches in the United States were divided between liberals and more confessional protestants, variously labelled fundamentalists and evangelicals. This led to a vast splintering of the latter grouping into scores of thousands of independent or quasi-independent congregations styling themselves bible churches, community churches, nondenominational churches and so forth. During the second half of the century this nebulous evangelical movement caught up with and surpassed the so-called mainline denominations, which had collapsed during the secularizing 1960s and after. Not surprisingly, one of the casualties of this splintering was a strong ecclesiology. The church had finally come to conform to John Locke’s liberal voluntarism, becoming little more than an association of like-minded believers choosing to belong—at least until they find something better elsewhere. Here the institutional church carries no more authority than component individuals choose to grant it.

For such Christians the divided nature of Christ’s Church ceases to be an issue at all, much less a scandal. As long as people are being spiritually fed somewhere, they are satisfied. Yet John Calvin was bold enough to call the Church our mother (Institutes, IV.1.4), stating that “there is no other way to enter into life unless this mother conceive us in her womb, give us birth, nourish us at her breast, and . . . unless she keep us under her care and guidance . . . .” Calvin, along with the other Reformers, had no wish to fragment the church, but to reform it. That they ended up breaking its unity was an unfortunate side effect of their efforts. Contemporary heirs of the Reformation, in so far as they have lost sight of the need for ecclesial unity, have imbibed more than a little of the individualism that dominates North American culture.

So what is left? If Roman and Orthodox exclusivism is not an option, and if contemporary evangelical ecclesiology, or the lack thereof, is not either, I would suggest that we need to own up to our disunity—to recognize and to lament the fragmentation of Christ’s body. No one denomination can claim to embody the entirety of Christ’s church, even if one or more may be closer to the fulness of the larger and deeper catholic tradition. And, yes, there is biblical precedent for this, especially in the Old Testament.

After the Israelites migrated from Egypt into Canaan under Moses’ leadership, they quickly divided along tribal lines, with Judah in particular claiming an identity distinct from the rest of Israel. In the account of the monarchy in 1 and 2 Samuel, we already see Judah and Israel opting for different monarchs. After the death of King Saul and most of his heirs, his remaining son Eshbaal, or Ishbosheth, briefly took his place over the northern tribes, while Judah opted for David as king. Two years later the two kingdoms were united under David and his successor Solomon. However, Solomon’s son Rehoboam retained only Judah, with the remainder of Israel choosing as king one of Solomon’s servants Jeroboam, who led them into the sin of idolatry. After that Judah and Israel took different paths as rival kingdoms, with Samaria founded as Israel’s new capital and Mount Gerizim as the central place of worship.

The division continued until the end of the northern kingdom at the hands of Assyria, which deported much of its population in 721 BC. Judah continued for another century and a half under the house of David until the Babylonian conquest in 587 BC. Both Israel and Judah claimed God’s favour, while God continued to care for both kingdoms as a single chosen people to whom he sent prophets calling for repentance. Elijah and Elisha were the greatest of the northern prophets, their story taking up much of the narrative in 1 and 2 Kings. God even sent Amos, a Judahite, to prophesy to the northern kingdom of Israel, something that would appear to defy the protocols of good foreign relations.

The greatest of the Judahite prophets were Isaiah and Jeremiah, whose prophecies are compiled in the books bearing their names. Much of the remainder of the Bible focusses on Judah and its remnant, which returned to the Holy Land under Persian King Cyrus, who permitted the building of the second temple. Meanwhile the remnant of the northern tribes continued with gentile admixture as the Samaritans, whom the Jewish heirs of Judah shunned. The bad blood between the two groups provides the backdrop for Jesus’ ministry in the gospels, and the parable of the Good Samaritan is recognized today even by those unversed in Scripture.

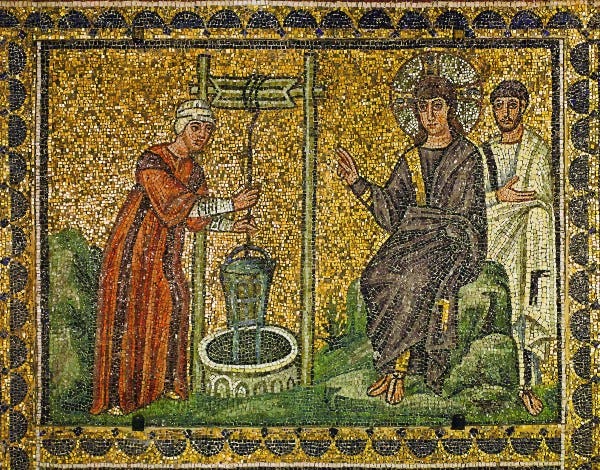

The fourth chapter of John provides a window into Jesus’ attitude to the unity of God’s people. Here we find his famous encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well. Their conversation surprised Jesus’ disciples, who didn’t know what to make of it. Some commentators stress that Jesus was talking with a woman and a foreign woman at that. Others argue that in so doing he was indicating that all divisions are ultimately meaningless before the eyes of God. But that’s not entirely right. Jesus never said that both Jews and Samaritans were correct or that both were wrong. In fact, he explicitly affirmed the Jewish side: “You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews” (John 4:22, emphasis mine). Yes, the house of David really was the bearer of the divine promise down through the generations. Yes, God really had chosen Mount Zion as the central location of valid worship. Yes, the northern kings had led the people into apostasy.

Yet this is not how Jesus ended the story.

“Woman, believe me, the hour is coming when neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem will you worship the Father. You worship what you do not know; we worship what we know, for salvation is from the Jews. But the hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father is seeking such people to worship him. God is spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth.” The woman said to him, “I know that Messiah is coming (he who is called Christ). When he comes, he will tell us all things.” Jesus said to her, “I who speak to you am he” (4:21-26)

Here Jesus pointed, not to the Jerusalem temple, whose role in the economy of salvation was nearly complete, but to himself. The house of David’s significance is that it points ahead to the coming Messiah, whom even the Samaritans were apparently expecting. In Christ the ancient enmity between Judah and Israel, between Jew and Samaritan, is now at an end. This is good news indeed.

Today Christendom is divided among Catholic, Orthodox, Reformed, Lutheran, Anglican and many more. Although I place myself firmly within the Reformed camp, I do believe that God cares for his people despite their divisions. We should continue to lament the divided character of God’s church and strive to overcome it as we are able. This cannot mean that we search for a least-common-denominator confession so weak as not to command anyone’s allegiance. This has been tried many times and found wanting. Instead we should keep to the truth as God has given us to see it, praying, not only that our separated fellow believers might see the light, but that we too might be open to correction from them where needed. This would be a fitting way to observe the anniversary of the Reformation as we await Christ’s return to bring his kingdom to fulfilment.

The post God’s Divided People: Biblical Lessons for the Church appeared first on Kuyperian Commentary.