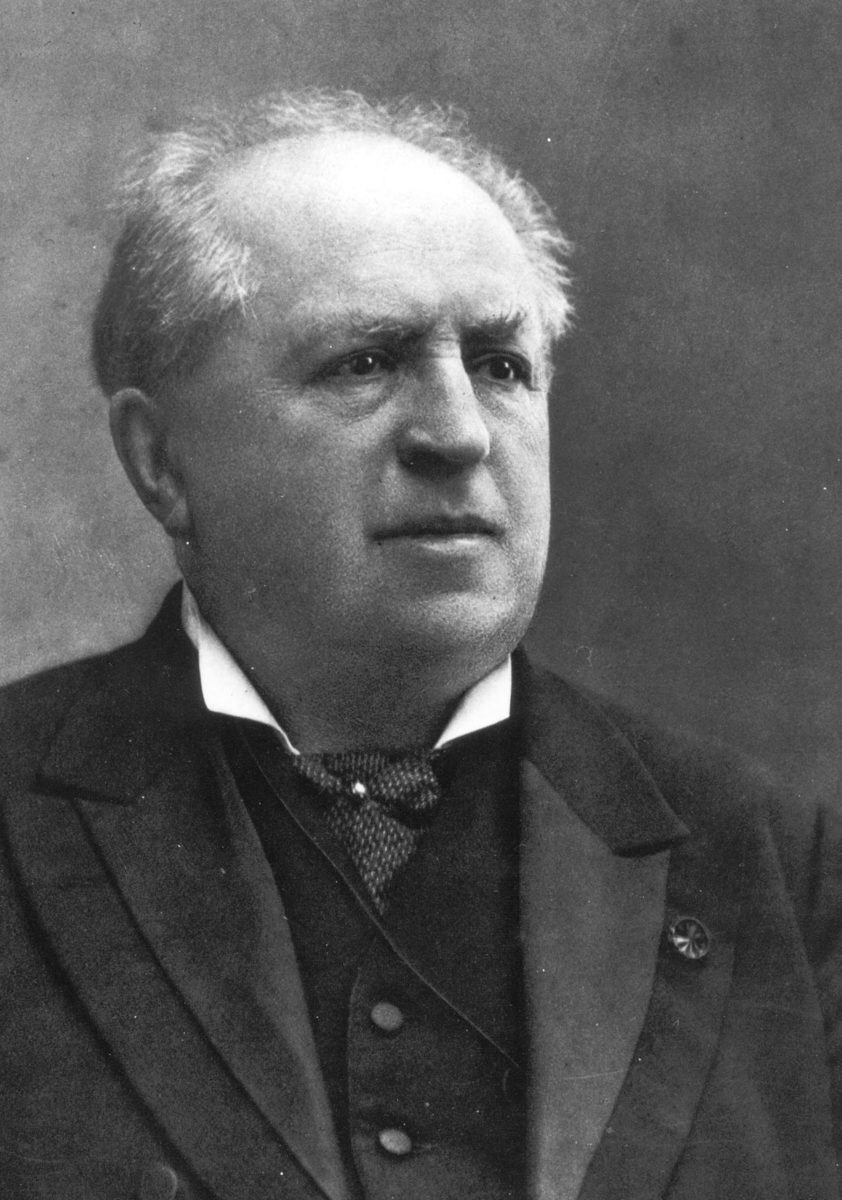

This is the fifth part of a six part article series on Abraham Kuyper’s Lectures on Calvinism. He gave these lectures at Princeton Theological Seminary over a series of days in October 1898. Happy International Abraham Kuyper Month!

Kuyper begins this lecture acknowledging the terrible idol that Art has become. He says, “Genuflection before an almost fanatical worship of art, such as our time fosters, should little harmonize with the high seriousness of life, for which Calvinism has pleaded, and which it has sealed, not with the pencil or the chisel in the studio, but with its best blood at the stake and in the field of battle” (p 142). Kuyper is reminding us to to see the vast difference between the artists in the art shop and the faithful men and women who sealed their confession with their very blood. While art does make an impact on culture and society, those who have died for the faith have the greater victory.

Kuyper then says, “Moreover the love of art which is so broadly on the increase in our times should not blind our eyes, but ought to be soberly and critically examined” (p 142). We should not create art for the sake of art, nor should we enjoy it for itself. We must do art for God’s sake and glory. This means a high and serious examination of all art in order to bring it in submission to God.

Kuyper also acknowledges how often art becomes its own separate religion. Those who reject true religion and spirituality will seek for religious experiences anywhere they can find it. He says, “And, unable to grasp the holier benefits of religion, the mysticism of the heart reacts in an art-intoxication” (p 143). One of the common ways people replace religion is to worship art. But Kuyper says the way to avoid that error is to“…keep [our] eyes fixed upon the Beautiful and the Sublime in its eternal significance, and upon art as one of the richest gifts of God to mankind” (p 143). If we see art as a good gift from God, then we can keep art in its proper place and use it as the tool and gift that it is from God.

Kuyper then turns to three key topics in art: religion and art, art in the worldview of Calvinism, and how Calvinism promotes art.

Calvinism Had No Religious Art

First, Kuyper points out that Calvinism did not develop an art-style of its own, like other schools or religions.

Kuyper explains why Calvinism did not develop its own art style. He begins by looking to the New Covenant and how God has given His people a more glorious mode of worship than what can be found in the Old Covenant. The current mode is a spiritual one. He says, “But when this ministry of shadows has served the purposes of the Lord, Christ comes to prophesy the hour when God shall no longer be worshipped in the monumental temple of Jerusalem, but shall rather be worshipped in spirit and in truth. And in keeping with this prophecy you find no trace or shadow of art for worship in all the apostolic literature” (p 147). Kuyper further explains that Aaron’s visible priesthood gives way to the invisible priesthood after the order of Melchizedek (p 147). Kuyper also describes it this way: “The purely spiritual breaks through the nebula of the symbolical” (p 147).

Kuyper argues that the older forms of religion were symbolic and ornamental because that was the more immature way to worship. He says, “Originally Divine worship appeared inseparably united to art, because, at the lower stage, Religion is still inclined to lose itself in the aesthetic form” (p 148). He then points out how God matures his people: “The more, on the other hand, Religion develops into spiritual maturity, the more it will extricate itself from art’s bandages, because art always remains incapable of expressing the very essence of Religion” (p 148).

Kuyper then uses an analogy to show how Religion and Art started out looking very similar to each other but when they are more mature we can see how very different they really are. He says this is like two babies who look the same when they are in the cradle but when they reach adult maturity, you can tell that one is a man and the other is a woman. He says, “And so, arrived at their highest development, both Religion and Art demand an independent existence, and the two stems which at first were intertwined and seemed to belong to the same plant, now appear to spring from a root of their own” (148).

Kuyper concludes this point saying, “Calvinism was neither able, nor even permitted, to develop an art-style of its own from its religious principle. To have done this would have been to slide back to a lower level of religious life” (p 149).

Art in Calvinism

Kuyper then turns to consider how Art fits in the worldview of Calvinism. He begins by reminding his audience that Religion must stay in its place: “However holy Religion may be, it must keep within its own bounds, lest, in crossing its lines, it degenerate into superstition, insanity, or fanaticism” (p 152). He then quotes John Calvin who writes, “All the arts come from God and are to be respected as Divine inventions” (p 153). As a direct gift from God, Art must be free to pursue its high calling before God. Art must be in service to God but that does not necessarily mean art should be subservient to the Church.

Rather, Kuyper shows how Art is not just for the Church or for Christians but actually a good gift to all men. He says, “In all Liberal Arts, in the most as well as in the least important, the praise and glory of God are to be enhanced. The arts, [Calvin] says, have been given us for our comfort, in this our depressed estate of life” (p 153).

Being a gift for all people does not lessen Art’s high calling. Kuyper says, “In view of all this we may say that Calvin esteemed art, in all its ramifications, as a gift of God, or, more especially, as a gift of the Holy Ghost” (p 153). This gift of the Holy Ghost is a general grace to all men but it is also a constant reminder that all artists must submit to Him.

Kuyper then argues that Art is designed to show us the Good and Beautiful that this world has lost through the corruption of sin and death. He says, “But if you confess that the world once was beautiful, but by the curse has become undone, and by a final catastrophe is to pass to its full state of glory, excelling even the beautiful of paradise, then art has the mystical task of reminding us in its productions of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster” (p 155). Art, when it reaches it full gory, points to the original form of the world and suggests the coming renewal of all creation at the hand of the Supreme Artist.

In this way, we see that Art is not really a subjective work but actually a work that must point to objective reality. God sets boundaries that Art must obey. Kuyper says, “If God is and remains Sovereign, then art can work no enchantment except in keeping with the ordinances which God ordained for the beautiful, when He, as the Supreme Artist, called this world into existence” (p 155). The power of Art is something that God created and Art only has power in so far as God has granted it that power. Kuyper adds, “And all this because the beautiful is not the production of our own fantasy, nor of our subjective perception, but has an objective existence, being itself the expression of a Divine perfection” (p 156).

Kuyper pushes this further saying that since all Creation is for God, this means ultimately that all Art and all Beauty is for God. He says, “Imagine that every human eye were closed and every human ear stopped up, even then the beautiful remains, and God sees it and hears it…” (p 156). Even the parts of this world that humans cannot see–distant galaxies, deep-sea creatures–all of these are wonderful works of art that God by Himself enjoys.

Kuyper summaries this point saying that every artist has to seek out his art and practice his skill. In this way, the artist does not look to himself to grow at art, but rather he must look to an objective standard to grow in his craft. And this plainly argues that art is something out beyond the artist; something that is found in God Himself (p 156).

Calvinism Promotes Art

Kuyper’s third point is that Calvinism also promotes Art. He says this happens because Calvinism sees art as a gift of common grace to all men. He says, “Calvinism, on the contrary, has taught us that all liberal arts are gifts which God imparts promiscuously to believers and to unbelievers, yea, that, as history shows these gifts have flourished even in a larger measure outside the holy circle” (p 160).

Kuyper than paints a wonderful picture for Christians: “The world after the fall is no lost planet, only destined now to afford the Church a place in which to continue her combats; and humanity is no aimless mass of people which only serves the purpose of giving birth to the elect. On the contrary, the world now, as well as in the beginning, is the theater for the mighty works of God, and humanity remains a creation of His hand, which, apart from salvation, completes under this present dispensation, here on earth, a mighty process, and in its historical development is to glorify the name of Almighty God” (p 162).

Art also plays an important role because “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, nor politics, nor religious life, nor even revelation can bring to light” (p 163).

Kuyper summarize this by saying that Calvin sends the three powers–Science, Religion, and Art–out to permeate all human life: “There must be a Science which will not rest until it has thought out the entire cosmos; a Religion which cannot sit until she has permeated every sphere of human life; and so also there must be an Art which, despising no single department of life adopts, into her splendid world, the whole of human life, religion included” (p 163).

So what Art has Calvinism promoted in the world?

Kuyper suggests his own dutch poets as one key example. For the English world, we can also see this influence in many famous English poets in history: Spenser, Milton, Shakespeare, and many others. In painting, Kuyper points to Rembrandt’s fine works. In Music, Claude Goudimel produced many great hymns for people to sing.

Several key ideas come from Calvinism which have impacted Art. Kuyper describes how the gospel highlights the dignity of all men. He says, “It is the common man, to whom the world pays no special attention, is valued and even chosen by God as one of His elect, this must lead the artist also to find a motive for his artistic studies in what is common and every-day occurrence, to pay attention to the emotions and the issues of the human heart in it, to grasp with his artistic instinct their ideal impulse, and, lastly, by his pencil to interpret for the world at large the precious discovery he has made” (p 166).

Kuyper also points out how sorrow and suffering in the world points to and highlights the suffering of Jesus in His ministry and work on the cross. He says, “And if thus far the eyes of all had been fixed constantly and solely upon the sufferings of the ‘Man of Sorrows’ some now began to understand that there was a mystical suffering also in the general woe of man, revealing hitherto unmeasured depths of the human heart, and thereby enabling us to fathom much better the still deeper depths of the mysterious agonies of Golgotha” (p 166).

Kuyper concludes this lecture by addressing those who complain about the lack of Calvinistic art today. He says they should be careful how they complain. Kuyper asks, “Has that man any right to complain about the stillness of the forest, who with his own hand has caught and killed the nightingale?”

abraham kuyper, Art, calvinism, International Abraham Kuyper Month

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, […]

[…] of the attractive that was misplaced and of anticipating its excellent coming luster,” he stated in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Artwork reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, […]

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, nor […]

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, nor […]

[…] of the attractive that was misplaced and of anticipating its good coming luster,” he mentioned in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Artwork reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, […]

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, nor […]

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, […]

[…] the beauty that has been lost and of anticipating its perfect brilliance to come,” he said. at a conference in 1898 at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation that neither science, […]

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, nor […]

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, nor […]

[…] of the beautiful that was lost and of anticipating its perfect coming luster,” he said in an 1898 lecture at Princeton Theological Seminary. “Art reveals ordinances of creation which neither science, […]