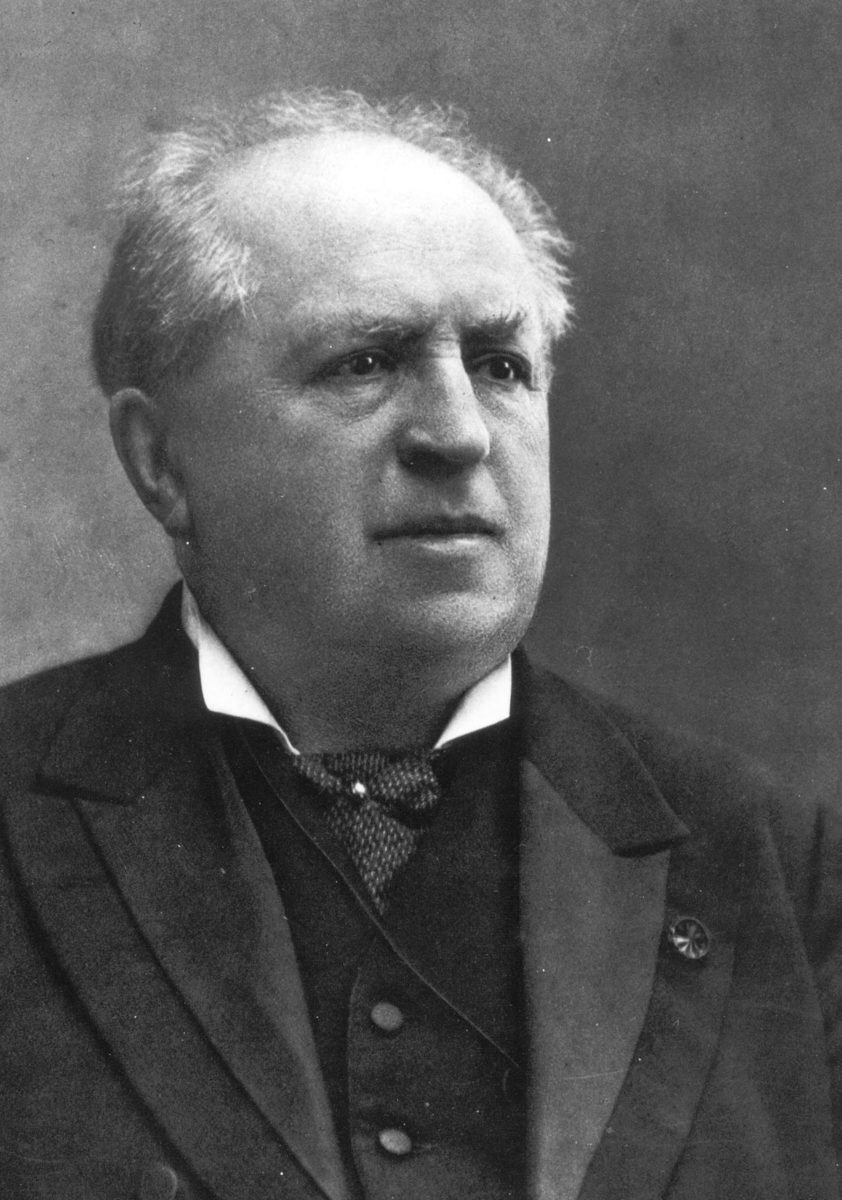

This is the fourth part of a six part article series on Abraham Kuyper’s Lectures on Calvinism. He gave these lectures at Princeton Theological Seminary over a series of days in October 1898. Happy International Abraham Kuyper Month!

In this lecture, Kuyper shows how Calvinism has impacted the field of Science. He argues that it has done this in four key ways: fostered a love for science, restored its full domain, set it free from unnatural bonds, and solved what Kuyper calls, the unavoidable scientific conflict.

Calvinism Fostered Science

First, Kuyper shows how Calvinism encouraged a true love of science. The love of science is bound up with a love of God’s character and and how He has lovingly predestined everything. Kuyper says it this way: “But if you now proceed to the decree of God, what else does God’s fore-ordination mean than the certainty that the existence and course of all things, i.e. of the entire cosmos, instead of being a plaything of caprice and chance, obeys law and order, and that there exists a firm will which carries out its designs both in nature and in history?” (p 114) The very ground of scientific investigation rests up the way God has orchestrated and ordained the world. In a random world, there would be no laws of nature for science to study. It is only in a world that is governed by the fatherly eye of God, can there be real science.

Kuyper says, “Thus you recognize that the cosmos, instead of being a heap of stones, loosely thrown together, on the contrary presents to our mind a monumental building erected in a severely consistent style” (p 114). We do not live in an evolving pond of goo but in a grand cathedral with stained glass windows and ornate flying buttresses. All of it is designed by the hand of a loving artist.

Kuyper concludes this point: “Faith in such an unity, stability, and order of things, personally, as predestination, cosmically, as the counsel of God’s decree, could not but awaken as with a loud voice, and vigorously foster love for science” (p 115).

Calvinism Restored Science’s Domain

Kuyper then turns to how science fared in other times and eras. In the late medieval age, science languished and was chained to a terrible despot. Kuyper says, “Christendom, it must be confessed, did not escape this error. A dualistic conception of regeneration was the cause of the rupture between the life of nature and the life of grace. It has, on account of its too intense contemplation of celestial things, neglected to give due attention to the world of God’s creation” (p 118). The erroneous divide between nature and grace in the late Medieval age sorely abused science and discouraged true scientific exploration.

Kuyper instead reminds us that that creeds of the Church confess that God is “Maker of heaven and earth” and as such we must also explore the earth in order to understand our maker. He also points out that “…the final outcome of the future…is not merely spiritual existence of saved souls, but the restoration of the entire cosmos…” (p 119). Given the cosmic scope of salvation, we must also investigate all of the cosmos in order to bring it under the lordship of Christ. Kuyper says this is what the Calvinistic confessions did in speaking “of two means whereby we know God, viz., the Scriptures and nature” (p 120).

In the Medieval age, there was a hierarchy in the Church that suggested earthly things were not really as important. Kuyper explains this by pointing to the clergy who ranked higher than the laity and then the monks who where were higher than the clergy. This structure pushed nature away and did not encourage a study of nature as a way to know and love God. Kuyper says, “Everything uncountenanced and uncared for by the church is looked upon as being of a lower character, and exorcism in baptism tell us that these lower things are really meant to be unholy” (p 123). The natural world was banished to the realm of the unholy and so could not reveal God. As such, it was not as important as so called “spiritual” matters. But Kuyper pushes back on that idea, saying, “…not only the church, but also the world belongs to God and in both has to be investigated the masterpiece of the supreme Architect and Artificer” (p 125).

Kuyper summarizes this point, saying, “A Calvinist who seeks God, does not for a moment think of limiting himself to theology and contemplation, leaving the other sciences, as of a lower character, in the hands of the unbelievers; but on the contrary, looking upon it as his task to know God in all his works, he is conscious of having been called to fathom with all the energy of his intellect, things terrestrial as well as things celestial…” (p 125).

Calvinism Set Science Free

Kuyper next traces the rise of the university and how it was eventually subjugated to the authority of the Pope and the Vatican. Kuyper says “Rome did oppose, not only in the Church, what was right, but also beyond its boundaries, the freedom of the word” (p 128). The Church often squashed truly free inquiry in the scientific realm. Kuyper says that in this era, “The right of free inquiry was unknown” (p 128). He then points to the example of Rene Descartes who “had to leave Roman Catholic France, found among the Calvinists of the Netherlands…a safe retreat” (p 129). Descartes, a Roman Catholic thinker, was not free in France but he found freedom in a Calvinistic country. He also found rivals to his philosophy. But there was freedom of thought and true scientific inquiry there. Something a Roman Catholic country could not endure.

Kuyper forcefully remarks, “As long, however, as the Church stretched out her velum over the entire drama of public life, the state of bondage naturally continued, because the only object of life was to merit heaven…” (p 129). The Church in the late Medieval age overreached its sphere of authority and tried to forbid science from growing and flourishing. It was the Reformation and particularly Calvinism that set science free. Kuyper explains, “This blessedness, for every true Calvinist, grows out of regeneration, and is sealed by the perseverance of the saints. Where in this manner the ‘certainity of faith’ supplanted the traffic of indulgences, Calvinism called Christendom back to the order of creation: ‘Replenish the earth, subdue it and have dominion over everything that lives upon it’’ (p 130). When a Christian rightly understands the secure gift of salvation, life is transformed from being a struggle to get to Heaven into a joyful exploration and study of nature seen correctly as a gift from our heavenly Father who has redeemed us from sin and delights in us studying His creation. Only the free gift of salvation can set science free.

Kuyper summarizes, “The cosmos, in all the wealth of the kingdom of nature, was spread out before, under, and above man. This entire limitless field had to be worked To this labor the Calvinist consecrated himself with enthusiasm and energy” (p 130).

Calvinism Solves the Conflict in Science

Finally, Kuyper turns to the conflict in science between unbelieving systems of worldliness and the true Christian worldview, e.g. Naturalism versus Super-naturalism. We see this conflict in our own day and it was one that Kuyper saw in his day as well. When Calvinism sets science free to do what science does, it will lead to conflict in science and scientists. This is one result of truly free scientific investigation. Kuyper says, “Free investigation leads to collisions” (p 130). However, this collision is not between faith and science as some might suggest. The reality is: there is no conflict between these two. Kuyper correctly says, “Every science in a certain degree starts from faith… (p 131). The true conflict then is between Naturalism and Super-naturalism. Or as Kuyper labels the two sides: Normalists and Adnormalists.

The Normalists “…reject the very idea of creation, and can only accept evolution” (p 132). While the Abnormalists: “…adhere to primordial creation over against an evolutio in infinitum” (p 132). The Normalists are the ones who believe in purely natural forces in the world and so they try to cling to the evolutionary process since it seems to be an explanation based on purely natural forces. While the Abnormalists recognize that there are both natural and supernatural forces in the world and so accept influences beyond the physical realm. But the key is to recognize as Kuyper does that “Each [has] its own faith” (p 133).

This is the primary conflict in science today. Kuyper rightly recognizes that both are “…in earnest, disputing with one another the whole domain of life” (p 133). It is not like Evolution is merely about origins. It is a life-system and so it is diametrically opposed to everything in the Christian life-system. Kuyper explains that the opposing system of the Normalists arose in the eighteenth century and took “up a position at the center” of the scientific community (p 135). And from that position, this materialistic perspective has impacted all areas.

But Kuyper shows how this materialistic position is not consistent with the nature of the world. He focuses on how the Normalist position cannot account for human consciousness. Calvinism “goes back to human consciousness, from which every man of science has to proceed as his consciousness” (p 136). Materialism has no way to explain this phenomenon and so the Normalist just assumes it on faith while at the same time denying that it is supernatural or derived from a deity. Kuyper says, “Calvin, however, does not excuse unbelievers on this account. The day will come when they will be convinced in their own conscience” (p 137). There is no way of escape from the truth of the supernatural. Everyone will acknowledge the supernatural perspective because everyone is assuming it already and using it in their own minds.

So how do we win in this conflict?

Kuyper points back to Calvinism setting science free to pursue true investigation. This is the need of the hour and that is why there is a current languishing in the scientific community. He says, “Free science is the stronghold we defend against the attack of her tyrannical twin-sister” (p 138). This twin-sister is the Normalist position. It looks and acts like true science but it is not really interested in true and free investigation. Instead, it is trying to supress the supernatural position in the scientific community. Kuyper says, “The Normalist tries to do us violence even in our own conscience. He tells us that our self-consciousness must needs be uniform with his own, and that everything else we imagine we find in ours stands condemned as selfdelusion” (p 138). In Kuyper’s time and in our own time, we see this relentless attack on the Christian perspective, and we know that we will be slighted and oppressed on this front, but we must not yield to the tyrants who are trying to control the sanctuary of our hearts (p 138).

Instead, Christian scientists must be bold. We must steal the tactics and courage from the opposing naturalists and pursue true scientific investigation. Kuyper says, “…if the courage, the perseverance, the energy, which enabled [the Normalists] to win their suit at last, will be found now in a still higher degree, with Christian scholars. May God grant it!” (p 139) Christian scholars must stand up and defend the truth and defend true scientific freedom.

Kuyper concludes saying that if the Church and State withdraw “…in order that the university may be allowed to take root and flourish in its own soil, then certainly the division, which is already begun, will be accomplished of itself and undisturbed, and in this domain also it will be seen that only a peaceful separation of the adherents of antithetic principles warrants progress–honest progress–and mutual understanding” (p 140). Kuyper predicts that eventually the current system of science, which is forced together by government controls, will collapse. He rightly sees that “…the days of its artificial unity are numbered, that it will split up” (p 141). When that happens, then science will flourish in true freedom again.

abraham kuyper, International Abraham Kuyper Month, Kuyper, Religion and Science