A friend asked a question recently on the subject of Christian education, along these lines: Why Greek rather than Latin? This isn’t the first time I’ve found myself tempted to talk about this subject; as it happens, I’ve had quite a few conversations about it over the years. And so perhaps now is as good a time as any to put a few thoughts in writing.

To begin with, a little background. Some Christian educators, particularly those in the so-called “Classical” tradition, regularly extol the virtues of learning Latin. The reasons are legion: it provides mental training; it helps with the grammar of (many) other languages, including English; it clarifies the etymology of many English words, thus broadening students’ English vocabulary; it opens the door to many great works of classical literature; and so on. I happily add my three-and-a-half cheers to the noisy, happy, Ciceronian throng. All these are, it seems to me, entirely worthy aspirations.

Yet we’ve chosen to teach our kids Greek instead. Why? Well, there are a few reasons. But first, two caveats.

First, I want to make it abundantly clear that this isn’t the sort of thing I want to get hot under the collar about. I think Latin is great. Seriously. Totally, wonderfully, utterly great. I’m not about to criticise anyone for teaching it to their kids. Frankly, if another family is already committed to giving their kids a thoroughly Christian upbringing, including the academic aspects of their training, then I’m 110% on their side. To start throwing brick-ends because they choose the language of Augustine rather than that of Athanasius seems to me rather like setting off across the Atlantic in a two-man rowboat, only to start complaining somewhere just west of the Scilly Isles that the other guy’s paddle is the wrong colour.

Second, the main reason why we’ve taught our kids Greek rather than Latin is very simple: Neither I nor my wife Nicole know any Latin, whereas I learned NT Greek during my ministerial training. NT Greek isn’t that different from Classical Greek, there are good textbooks available for both, and you can even do a GCSE in the latter. Whatever the merits of the arguments below, in our case our own ignorance was the most significant factor.

I’m quite sure it’s possible to teach Latin to children without knowing the language to start with – there’s no good reason why you couldn’t do with this subject what most homeschooling parents do to some extent with all subjects, namely, learn by teaching with the aid of high quality resources. But at least in foreign languages I reckon there’s some advantage in the teacher having a degree of expertise. And when all’s said and done, why make life more complicated than it already is? In short, if I knew Latin, and not Greek, our kids would probably be chanting amo, amas, amat rather than luō, lueis, luei.

Having said all that, I do think there are some good reasons why Greek should at least register as a contender in the foreign-language stakes.

First, Greek shares many of the advantages of Latin.

- Like Latin, both koinē (NT) and Classical Greek are a heavily inflected and highly regular languages (Latin is perhaps more regular, but the point stands), which means that they open the door to a rigorous understanding of the many grammatical concepts that are important for understanding other languages (at least, many of the Indo-European ones).

- Learning Greek, like learning Latin, requires (and indeed inculcates) mental discipline.

- Like Latin (though perhaps to a lesser extent), Greek lies behind many of today’s English words, which helps to broaden the students’ vocabulary. (Personally, I’m less convinced than some people that the related “etymology of English words” point is really an advantage, since the contemporary meaning of many words is not actualy clarified by their etymology at all, but that’s a discussion for another day.)

Second, the oft-quoted disadvantage of Greek – namely, that the alphabet is different from the English alphabet – is a complete red herring. For one thing, the Greek alphabet is a jolly good thing to know anyway, regardless of whether you’re learning the language. If you’re not teaching it to your kids, you should be. And for another thing, it takes the average kid about four days of chanting for 10 minutes a day to completely master it. Hardly a decisive hurdle.

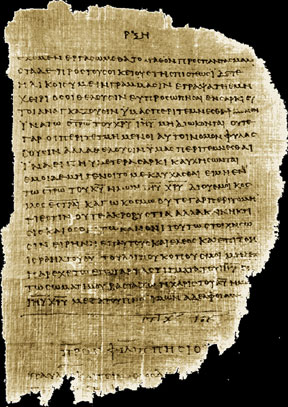

Third – and here comes the really significant point – koinē Greek offers one massive, unquestionable, glaring-you-in-the-face-kind-of-obvious advantage over Latin: It’s the language of the New Testament. For all of the potential benefits that might be reaped by reading the words of Cicero in the original, I submit that a substantially greater benefit is to be obtained by reading the words of Jesus.

I’m not sure if many folks who learned Latin at school ever read Cicero for fun in adulthood. I’m very sure that every Christian who learns Greek ought to be reading the Bible every day. If the time that had been spent learning Latin had instead been spent learning the language in which the Holy Spirit chose to inspire 25% of the Bible… well, it doesn’t really need spelling out, does it?

Of course, someone might point out, by this logic one ought to learn Hebrew, and not just Greek (or Latin). I agree. If I had competence enough (and time), I’d teach that to my three kids as well. But you can’t do everything. And remember, I’m not criticising the pro-Latin crowd; I’m simply suggesting that another extremely worthwhile contender in the Ancient Language stakes is the tongue in which God our Father chose in his sovereign providence to record the words of his Son.

(This article originally appeared as one of a series of posts on the subject of Christian Education on the Minister’s Blog at Emmanuel Evangelical Church, London, England.)