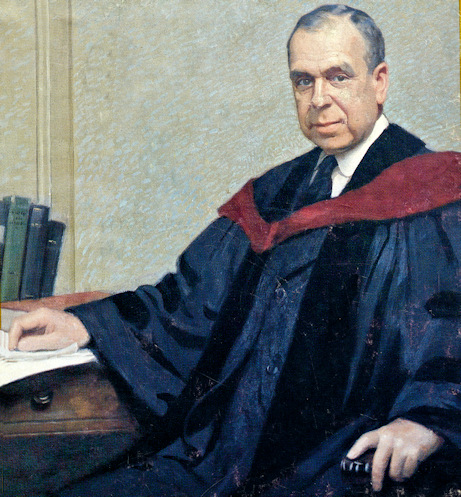

This year marks the centenary of an important book clarifying a crucial moment in the history of North American Christianity. John Gresham Machen wrote Christianity and Liberalism (New York: Macmillan, 1923) as an analysis and critique of a phenomenon making its way into the Protestant churches of North America, threatening to erode the faith of ordinary Christians in the pews. Born in 1881 in Baltimore, Machen was one of the last of the great Princeton theologians, following a long line of men associated with Princeton Theological Seminary, including Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, A. A. Hodge, and Benjamin B. Warfield.

During the 19th century, Princeton Seminary, founded in 1812, was a bastion of Reformed orthodoxy and remained so into the first three decades of the 20th. Nevertheless, by the turn of that century, the supporting denomination, the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA), was already in the process of changing, and not for the better. Pulpits were increasingly occupied by ministers whose preaching was more influenced by the ideologies of the day than by sound biblical interpretation. The major ideology of the day was scientism, the conviction that the only genuine form of knowledge was that accessible by the scientific method. Other claims to knowledge were to be greeted by a general posture of scepticism. Even Scripture and the doctrines of the Christian faith must be subjected to the canons of science, which in turn were thought to determine what we can and cannot accept of that faith. Claims to miracles, for example, cannot be scientifically vindicated and must thus be relegated to the status of primitive myths. All that remains of Christianity is its supposed ethical core.

Machen analyzed this trend under the general rubric of liberalism. What is liberalism? According to Machen, “the many varieties of modern liberal religion are rooted in naturalism—that is, in the denial of any entrance of the creative power of God (as distinguished from the ordinary course of nature) in connection with the origin of Christianity.” Modern liberalism attempts to answer the question whether Christianity can “be maintained in a scientific age.” This has led liberal Protestants to abandon one doctrine after another until the religion with which they are left is no longer Christianity, but a completely different one: “despite the liberal use of traditional phraseology modern liberalism not only is a different religion from Christianity but belongs in a totally different class of religions.”

But there’s more. Religious liberalism, while retaining the traditional language of Christian faith, effectively drains it of its meaning, substituting something ostensibly more palatable to modern sensibilities. Liberals view Jesus merely as an example of faith rather than as an object of faith. Jesus was a great teacher whom we ought to follow. Christianity, however, views Jesus as the incarnate Son of God whose life, death by crucifixion, and resurrection have atoned for our sins, rescued us from the power of death, and given us new life. If, however, we are limited to following Jesus’ teachings, we know in our hearts that we will never be able to do so perfectly. Thus we remain in our sins. But the good news of Jesus Christ is that we do not save ourselves; God himself has accomplished something we could never hope to on our own, even with a perfect example to emulate. In Machen’s words:

Among the defects of liberalism is an inattention to sin, a tendency towards pantheism, an overly optimistic assessment of human nature, an inclination to diminish the reality of God’s judgement, and a lopsided focus on social issues, as if resolving these would somehow usher in the kingdom of God.

But the chief characteristic of liberalism is found in its view of authority. For the Christian, the ultimate authority for faith and life is the word of God, embodied in the divinely inspired Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. For the liberal, authority is vested in the religious experience of the believer. This is something that ties the liberalism of a century ago to today’s progressive Christians, as many now prefer to call themselves. No longer is the denial of miracles a distinguishing mark. Progressive Christians do not necessarily deny, say, the virgin birth or the literal resurrection. They may affirm most or even all the principal doctrines of the faith, yet retain a focus on experience through which they implicitly insist on filtering them.

Thus when I read something in the Bible, I can safely ignore the 2,000-year tradition of biblical interpretation and test it against my own personal experience of God. If I find a particular item in the Scriptures unappealing or offensive, I reserve the right to reject or ignore it. The result is a cafeteria or designer-label Christianity that leaves me fully in charge of my own spirituality, inoculated against anything that might challenge my own identity and aspirations. Moreover, as a sovereign individual, I must resist the discipline of a community of faith, even as that community is progressively reduced to a mere collection of like-minded individuals, infinitely expandable in principle through constant pulpit appeals to a shrinking congregation to be ever more inclusive.

Today the major ideology making its way into the churches is no longer scientism, whose pretensions were long ago skewered by the likes of Thomas Kuhn and Michael Polanyi. Now the regnant ideology is expressive individualism, seemingly tailor-made for a century-old movement focussed on experience. But much as 20th-century liberalism led to the collapse of the old-line Protestant denominations, the newer progressivism is unlikely to have a different outcome.

Of course, not everything in Machen’s book has aged well. His reference to Jesus as a “supernatural Person” suggests an unfortunate effort to categorize Jesus rather than simply to take him as he is, namely, the unique incarnate Son of God who saves. Furthermore, Machen’s definition of miracle as “the supernatural manifesting itself in the external world” and as something “that takes place by the immediate, as distinguished from the mediate, power of God” is not particularly persuasive, in my view. A miracle may indeed be unexpected, but that does not exclude the possibility of proximate causes capable of being observed and noted. If scientists ever succeeded in identifying, say, geological or meteorological origins for the plagues recorded in Exodus, that would in no way disprove their miraculous character. I find novelist Graham Greene more convincing on this point: if the extraordinary were to happen repeatedly, people would simply deny its miraculous character and adjust their worldviews accordingly. The fact is that the natural and the supernatural are not two different phenomena; creation itself, along with the laws by which it functions, is a miracle of God. But one needs to be open to the miraculous to recognize it.

Apart from these minor defects, Machen’s book remains relevant. True, the movement he analyzes has mutated into something quite different from what it was in 1923. Nevertheless, the same central assumption is still in play, namely, the focus on religious experience as supreme authority for faith and life. As such, we would do well periodically to reread Christianity and Liberalism to remind ourselves of how the ideologies of the day, whatever form they take, can seep into our congregations and subtly distort the teachings of the gospel. The best antidote, of course, is simply the clear and enthusiastic proclamation of the unadulterated gospel message, which is changing lives and bettering societies around the globe.