Background

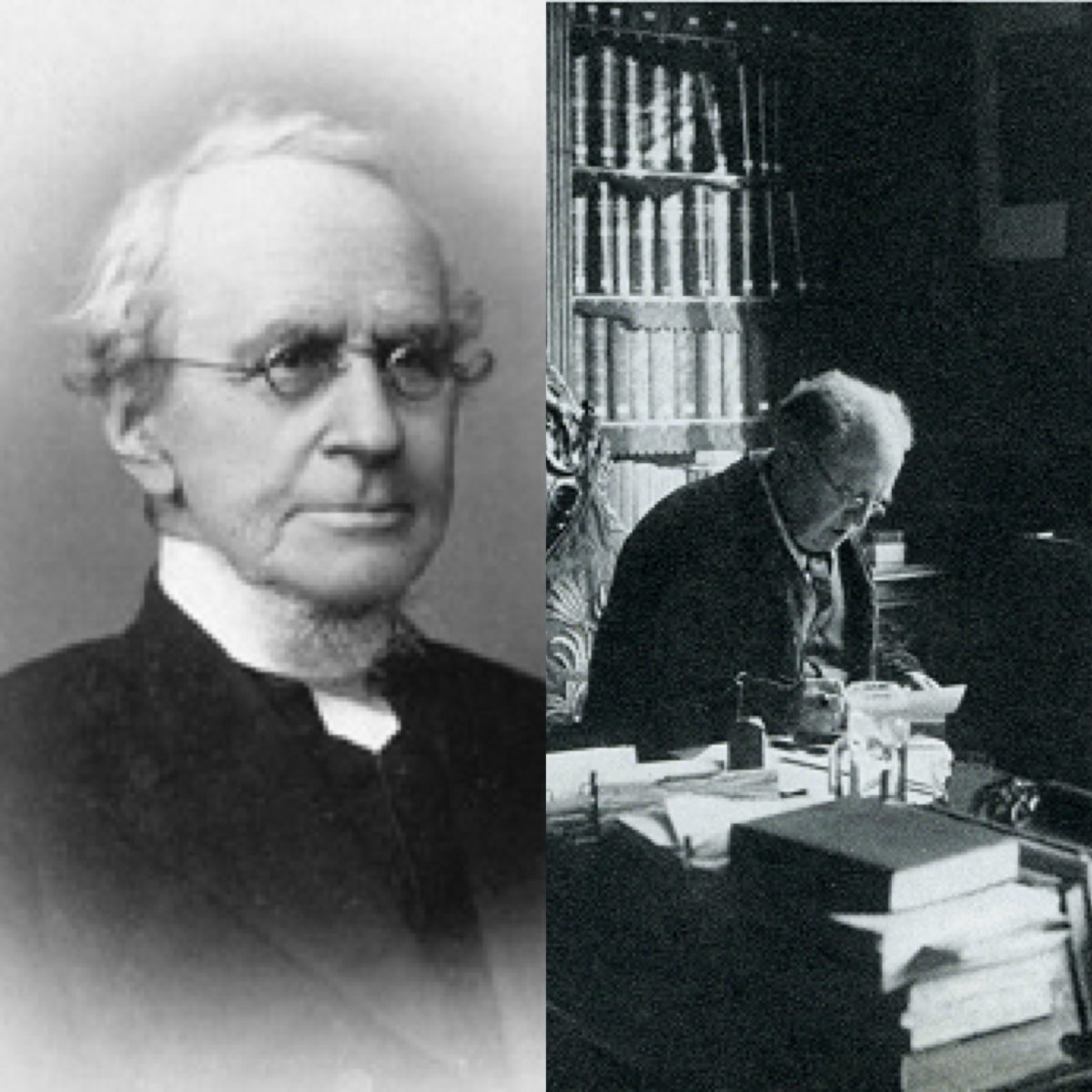

In 1844 the newly formed seminary of the German Reformed Church called Philip Schaff to be professor of Church history. After trekking from Berlin to Pennsylvania, Schaff promptly delivered the inaugural lecture for the semester. This lecture, later published with an introduction by Schaff’s colleague John Nevin as The Principle of Protestantism, encapsulated the Reformed, ecumenical, and sacramental emphasis, which came to be known as Mercersburg Theology. Half a century later another European theologian who, like Schaff, was heavily influenced by German Idealism landed on American soil to lecture on a theological system he had been developing in the Netherlands. In these addresses, later published as Lectures on Calvinism, Abraham Kuyper defended a Neo-Calvinistic worldview that was culturally all-encompassing. Christ’s redemption, argued Kuyper, was not limited to the so-called “sacred” or “spiritual” realms, but embraced art, politics, commerce and every sphere in which man is a participant.

To be sure, the legacies of Neo-Calvinism and Mercersburg are not equal in regards to size or influence. While the Dutch Reformed Church has flourished in Europe, South Africa, Canada, and America, Mercersburg theology has never reached more than a modest, albeit fervent, following. In addition to being smaller, the Mercersburg family tree looks very different from that of the Neo-Calvinists. The Mercersburg tree, shaped by more churchly conversations, grew in a more liturgical, ecumenical direction, while the Neo-Calvinist tree bent toward cultural engagement.

My argument is not that the Mercersburg and Neo-Calvinist families are arguing for the same thing only with a different vocabulary. The branches of both trees have reached too many and too far for such a hypothesis to be submitted let alone taken seriously. Rather, my argument is that while the trees do not share identity, they do share similarity. This similarity, far from being coincidental or contrived, I will argue is naturally and organically found in the writings of the Mercersburg and Neo-Calvinist founders. Indeed, it is my contention that the Mercersburg and Neo-Calvinist trees share similar roots and grew in the like soil of a decidedly non-puritanical reading of Calvin.

Thus, what follows is not an attempt to read Nevin as a Dutchman or Kuyper as an Antebellum Presbyterian. Rather, my aim is more modest and will come in three parts. First, I hope to show that both parties were reacting to the same problem; namely, the radical subjectivism produced by the Enlightenment. Second, in contrast to the modern strain of individualism, both parties sought to locate the nexus of ecclesial and epistemological authority squarely in the active, current reign of Jesus. Lastly, I will offer two ways in which both camps could be strengthened by a close reading of one anther’s texts. Such mutual appreciation, I will conclude, will assist both camp’s efforts of faithfulness and relevancy.

Amsterdam

In his Stone Lectures, Abraham Kuyper sought to develop a life system by which the modern Christian could view the world. Kuyper was repulsed by what he saw as the competing life system coming out of the French Revolution, which sought to deliver autonomy to the individual. “Modernism,” said Kuyper, “is bound to build a world of its own from the data of the natural man, and to construct man himself from the data of nature.” Such a worldview, which sought elevate the modern man, ultimately proved, ironically, inhumane. This reality led Peter Heslam to make the following observation:

“[Kuyper] denounced socialism for its revolutionary nature that rode roughshod over democratic freedoms and resulted merely in the replacement of one sort of tyranny with another. It also excluded any reference to a transcendent ‘other,’ basing its political programme solely on human reason – which is fallen. [Another] problem he found with socialism was its secular materialism, which reduced humanity to the realm of nature, robbing human beings of the dignity they have by virtue of being created in the image of God.“

To understand the system developed by Kuyper one must understand the goal: human flourishing. A theocracy in which humans are suppressed and abused of their rights was not the aim of Kuypers thought. Rather, it was Kuyper’s simple contention that society flourishes when the members have a right view of God, others, the world, and ultimately themselves. This “right view” will never come from the data of man, but will be found in the sovereignty of God. To understand creation one must understand the Creator.

In reaction to the story told by the French Revelation, Kuyper offered a rival paradigm through which reality could be interpreted. This paradigm offered a worldview outside of the individual. The individual can understand an object not exclusively by his own musing or senses, but by surmising its creational intent, its fallen nature, and the ways in which Christ offers redemption. Kuyper’s worldview challenged the modern schema point for point. By giving authority to Christ, Kuyper released man from his false since of autonomy. Christ’s reign was not bound to the church, but was all encompassing. Said Kuyper, “Not only the church, but also the world belongs to God and in both has to be investigated the masterpiece of the supreme Architect and Artificer.”

Mercersburg

Having placed Kuyper in his proper context we now turn our attention John Nevin and Philip Schaff. Most Reformed Christians are familiar with Mercersburg Theology only insofar as it relates to Princeton Theology, which is to say they see Schaff and Nevin through Hodge-tinted glasses. Of Charles Hodges’ considerable polemical writings, few were more harsh than his criticism of Mercersburg generally and Nevin particularly. Ironically, Nevin’s first teaching assignment was substituting for Hodge while Hodge was studying in Germany. Upon Hodge’s return, he not only found Nevin quoting Schleiermacher favorably, but also saw Nevin implementing much of the vocabulary of German Idealism. To be sure, understanding the Mercersburg/Princeton debate is crucial to understanding both movements. However, in order to properly reckon with the heart of Schaff and Nevin’s concerns, one must frame Mercersburg not primarily as a reaction to Princetonian Presbyterianism, but as a sharp rebuttal to the sectarian revivalism of Charles Finney and the Second Great Awakening. Nevin and Schaff viewed Finney and company as the fruit of a puritanical, individualistic reading of Scripture. One can be certain that Finney was in the back of Schaff’s mind as he wrote:

“As Catholicism towards the close of the Middle Ages settled into a charter of hard, stiff objectivity, incompatible with the proper freedom of the individual subject, now ripening into spiritual manhood; so Protestantism has been carried aside, in later times, into the opposite error of a loose subjectivity, which threaten to subvert all regard for church authority.“

This quote, perhaps better than any other, sums up the chief concern of the Mercersburg project. Neither Schaff nor Nevin wanted to question the validity of the Reformation. On the contrary, Schaff insists that the “stiff objectivity” of Catholicism was incompatible with the faith of Christianity. However, Mercersburg wanted to show that the extreme focus on human emotions and feelings was out of step with historic Christianity; indeed, out of step with the best of the Reformed tradition. Nevin and Schaff saw the remedy to the ill brought on by revivalism as threefold.

To begin, they sought to revive a view of the Eucharist more in step with Calvin than their modern Presbyterian peers. Says Nevin:

“The Question of the Eucharist is one of the most important belonging to the history of religion. It may be regarded indeed as in some sense central to the whole Christian system. For Christianity is grounded in the living union of the believer with the person of Christ; and this great fact is emphatically concentrated in the mystery of the Lord’s Supper; which has always been clothed on this account, to the consciousness of the Church, with a character of sanctity and solemnity, surpassing that of any other Christian institution.”

Mercersburg not only found a memorial view of the Supper anemic, but saw it as the outworking of rationalistic philosophy. Such a philosophy, they maintained, was out of step the hermeneutic employed throughout the church’s history. While the modern church viewed salvation as purely personal and subjective, only dealing with the emotive self, Nevin and Schaff offered a robust sacramentalism which saw baptism and the Lord’s Supper as effectual. This view, they argued, was not only in step with the Reformed tradition, but flowing from it. Says Nevin:

“[The Reformed position] allows the presence of Christ’s person in the sacrament, including even his flesh and blood, so far as the actual participation of the believer is concerned … A real presence, in opposition to the notion that Christ’s flesh and blood are not made present to the communicant in any way. A spiritual real presence, in opposition to the idea that Christ’s body is in the elements in a local or corporal manner. Not real simply, and not spiritual simply; but real, and yet spiritual at the same time. The body of Christ is in heaven, the believer on earth; but by the power of the Holy Ghost, nevertheless, the obstacle of such vast local distance is fully overcome, so that in the sacramental act, while the outward symbols are received in an outward way, the very body and blood of Christ are at the same time inwardly and supernaturally communicated to the worthy receiver, for the real nourishment of his new life. Not that the material particles of Christ’s body are supposed to be carried over, by this supernatural process, into the believer’s person. The communion is spiritual, not material. It is a participation of the Saviour’s life.”

Here, Nevin is clear to distance himself from any view of the Supper that seeks to locate physical flesh and blood in the elements themselves. Nevin, being an heir of the Reformation, held firmly to the notion that the believer takes the Supper by faith. Nevertheless, Mercersburg does view the sacraments as themselves objectively—yet mysteriously—nourishing and effective.

Second, Mercersburg placed the accent of salvation on the incarnation rather than the atonement. Writes Nevin, “The incarnation is the key that unlocks the sense of all God’s revelations. It is the key that unlocks the sense of all God’s works, and brings to light the true meaning of the universe… All nature and all previous history unite, to form one grand, universal prophecy of his presence.”

Here, Mercersburg is again seeking to locate the salvation of the individual in a more communal, covenantal context. Jesus did not arrive simply to “take away my sins.” While Nevin and Schaff would not deny personal salvation, in focusing on the incarnation they emphasize the ailment of creation as a whole. That creation and the Creator have been separated is of chief concern in Mercersburg’s reading of the drama of salvation. In Jesus, God has united the Creator to the creation, overcoming the predicament of sin once and for all.

Third, Mercersburg argued for a hearty ecumenism. It is on this point that the debate between Mercersberg and Princeton (chiefly Hodge) reaches its fever pitch. Hodge agrees that the sectarianism of Protestantism is a tragedy. However, Hodge thought the institutional, ecclesial ecumenism Mercersburg called for was unwarranted. Indeed, Hodge is quick to point out that, despite the number of denominations, American Protestantism was far more united than Roman Catholicism. Clearly, the unity of which Hodge was speaking was a spiritual unity, a familiarity and kinship between Christians. Nevin and Schaff identified the criteria Hodge used to make such a claim and quickly rebutted. In using such a subjective standard to measure catholicity in the church, Mercersburg saw Hodge as essentially erring on the side of the revivalists. The unity called for by Mercersburg was to be measured in concrete, ecclesial identifiers.

Agreement Between Amsterdam and Mercersburg

Abraham Kuyper, as we have seen, was facing a similarly subjective individualistic culture. Kuyper’s responses, however, have been of a different nature than Mercersburg’s response to modernity. It is my contention that such differences originate not out of two fundamentally distinct theological visions. Rather the different emphasis arise from the distinct subject matters being addressed by both parties. In other words, Kuyper is addressing modernity manifested in the secular culture, while Nevin and Schaff are responding to a baptized modernity. That the two visions in fact share a common and unified theological vision is seen nowhere more clearly that in the liturgical theology of Neo-Calvinism and Mercersburg.

As has been demonstrated, Mercersburg offers a high-church solution to the problem of modernity. What will now be demonstrated is that Kuyper too, when speaking of the woes of the modern church, defends a liturgical, sacramental emphasis.

One could be forgiven for not thinking Kuyper a high churchman. The following sentence is a good example of a Kuyperian quote which, when taken out of context, seems to diminish the role of the church: “Worship must be the one, grand, royal action of our whole life, in all our thoughts, words, and deeds. We are always God’s priests, called to serve his holy purposes.”

Taken on its own, such a quote could lead one to view corporate worship as optional at best and unnecessary at worst. However, Kuyper follows the previous sentence with the following, “However the service of God for the congregation does not come to full expression until the congregation assembles in worship for the express purpose of bringing God honor, praise, and prayers.”

Once Kuyper addresses the churchly face of Modernity, it is clear his intuitions align with Nevin and Shaff’s. Indeed, Kuyper was ageist at the rationalistic approach taken in worship. Says Kuyper, “Many still have the idea that the real purpose of holding church is to explicate the Bible to those who have gathered, and then to admonish or comfort the listeners. People do not understand at all the difference between a Bible lesson, a Bible discussion, and a worship service. They think it is a worship service when the minister discusses one or two verses, and that it is a Bible lesson when he discusses a whole chapter.”

When the corporate body worships, it is not simply to be educated, but fed and nourished by the body’s head. “God also acts.” Said Kuyper in reference to the liturgy: “God is not a static presence.” Kuyper applied his objectivity in similar ways as the Mercersburg founders not only in relation to liturgy, but also to ecclesial structure more generally. While Kuyper was extremely appreciative of much of American religion and political life, her ecclesial structure were never a thing to be emulated in the Kuyper’s estimation. Quips Kuyper, “It is quite common in America, especially in the larger cities, for a minister to start his own church, attract whoever will come, and maintain his church from the contributions that come in. Such a church is thus literally an independent business run by the minister, without any confessional forms and without connections to other churches. It is nothing other than a circle gathering around a talented speaker.” To make the worship service centered on a talented speaker, or an emotional experience, is to privatize the faith. As Richard Wentz says in his analysis of Nevin, “radical catholicity is an expression of public faith.”

While, no doubt, differences remain between Neo-Calvinism and Mercersburg Theology, it is clear that the heart of both movements is a desire to recognize Jesus’, rather than the individual’s, authority both in the church and the culture. With such a common vision established, we will now consider two areas in which the movements can sharpen and encourage one another toward greater faithfulness and relevance.

What Amsterdam can learn from Mercersburg

One of Hodge’s chief complaints against the Mercersburg Theology was, despite its plea for objectivity in many areas, its ultimate subjectivity and speculation when it came to theology. The motive behind such subjectivity is clear: in emphasizing the incarnation, Mercersburg wanted to see salvation as a person, rather than as a system or a particular doctrine. Agreeing with B.B. Warfield, Mercersburg would maintain that one is not saved by faith alone, but by faith in Christ alone. In other words, Mercersburg wanted to be careful to not put confidence in an abstract Christology, but in the incarnate Christ himself.

Thus, Mercersburg can serve as a reminder to the Neo-Calvinists that they are not saved by a story, but in a story. Neo-Calvinists are just as susceptible to abstracting the faith as the systamatician who views the Bible as an instruction manual. Salvation does not come, Nevin would insist, as the result of an adopted worldview! Rather, salvation comes through the person of Christ. To be sure, once one is saved, a worldview is unavoidable and one’s presuppositions must be challenged and refined. However, Mercersburg would be wary of any definition of Christianity that sought to place the emphasis on an intellectual system rather than the person of Christ.

What Mercersburg can learn from Amsterdam

The Neo-Calvinist tradition has much to share with Mercersburg, a movement whose conversations have tended to be exclusively sacramental and liturgical. Nevin’s view of what Kuyper would call “spheres” is, as a matter of fact, remarkably similar to the Neo-Calvinist tradition. However, in emphasizing the unique role of the church, Mercersburg needs to be reminded of the doxological nature of all of life. Our liturgy in church shapes the liturgy we practice in business, politics, and sports. Today, more than ever, the individualism and privatization of faith is afoot. Catholics rail against the Pope for making the simple observation:

“…the Gospel is not merely about our personal relationship with God… The Gospel is about the kingdom of God; it is about loving God who reigns in our world. To the extent that he reigns within us, the life of society will be a setting for universal fraternity, justice, peace and dignity. Both Christian preaching and life, then, are meant to have an impact on society. We are seeking God’s kingdom.”

While such a statement should be understood as ordinary Christian faithfulness in the world, the spirit of the age bauchs at the notion that the “sacred” should intermix with the “secular.” Neo-Calvinism reminds Mercersburg that a faith, no matter how liturgical or sacramental, remains private and individualized so long as it neglects its public and societal responsibilities.

Conclusion

My goal has been to set the theology of Neo-Calvinism and Mercersburg in the context of the modern question “can you privatize Christianity?” Both Neo-Calvinism and Mercersburg answer with a hearty and robust “no!” In order to read both theologies well, one must realize that Kuyper was posed this question by a fierce European secularism. Thus, his theology grew in a more political direction. Nevin and Schaff were posed the question from those inside the church, those who wondered if the main criteria for salvation was not a “personal relationship with Jesus,” complete warm feelings and pious thoughts. Thus, the Mercersburg Theology bent toward liturgical and churchly concerns. It is only in a proper appreciation of both movements that we can hear the voice of King Jesus saying to his creation not only “mine!” but also through the mystery of the incarnation hear him cry “here!”