The cry for American world “leadership” shows us that C. S. Lewis was right about punishment

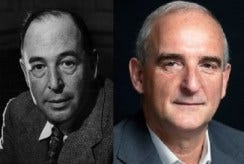

One of my favorite essays by C. S. Lewis is his piece collected in God in the Dock on “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment.” You can read it in the internet graveyard here (by “graveyard” I mean Angelfire; my older readers will understand). Lewis viewed himself as defending the traditional view of punishment–people were punished if and when and to the extent that they deserved to be punished. Lewis’ view leaves me with questions about the history of punishment in Christian lands, but I think his basic thesis holds up.

The “humanitarian” view, which Lewis criticized, is actually two views.

You regard a person who has committed an act as sick and in need of healing. Thus you force treatment on him for his own good.

You regard a person who has committed an act as a bad example and public punishment as a way to use him as a deterrent. You do something unpleasant and public to him so others will avoid doing the same act so they won’t receive the same unpleasant treatment.

Of course, both of these effects can be hoped for in the traditional theory of punishment. Lewis just insisted they are secondary and limited. Once you have punished a thief, he is a free man whether or not he has learned not to steal.

What made me think about Lewis’ essay recently is the rhetoric I am hearing about the need for American “leadership.” I confess, I have a hard time using that word when it seems so obvious to me that “leadership” means the frequent and energetic committing of mass homicide in other countries that are no danger to the United States.

But I will leave that aside for another day.

Today I read this piece by Roger Cohen in the New York Times: An Anchorless World. An anchor, again, would be a superpower willing to commit mass homicide in other nations when the leaders of those nations disobey the superpower. One might respond that I am being cynical by not mentioning real crimes committed by the target nation. Please read below. An “anchor” is treated as the self-evident need in the world in order to perpetuate civilization.

Again, I will leave aside much of my opinion of the alleged argument in this piece.

What made me think of C. S. Lewis’ essay on punishment was that Cohen’s argument was completely dependent on certainty about the truth of the claim of “…Assad’s devastating chemical weapons attack more than three weeks ago.” Assad attacked “his own people” (who we should now bomb as a reprisal) with chemical weapons.

No he didn’t.

At least, we have barely any evidence and nothing like proof that he did so. The people who are certain of it should be publicly repenting about lying about Iraq since, if Assad is guilty, it was their own past history of deception that has taken away their credibility with the American people. (In which case, all those who sincerely believe in Assad’s guilt should all be publicly condemning the Bush Administration and the collaborators in Congress–Joe Biden and Hillary Clinton chief among them–for destroying the credibility of the US government resulting in our present inability to launch.) Multiple witnesses from the Administrations classified briefings say that it makes them more skeptical of Assad’s guilt, not less.

Why does Cohen not provide his reader with any reason to believe that Assad used chemical weapons?

Back when I read Lewis on punishment I thought his criticism of the second humanitarian theory, the deterrent theory, was an ad absurdum argument.

If we turn from the curative to the deterrent justification of punishment we shall find the new theory even more alarming. When you punish a man in terrorem, make of him an ‘example’ to others, you are admittedly using him as a means to an end; someone else’s end. This, in itself, would be a very wicked thing to do. On the classical theory of Punishment it was of course justified on the ground that the man deserved it. That was assumed to be established before any question of ‘making him an example arose’ arose. You then, as the saying is, killed two birds with one stone; in the process of giving him what he deserved you set an example to others. But take away desert and the whole morality of the punishment disappears. Why, in Heaven’s name, am I to be sacrificed to the good of society in this way?—unless, of course, I deserve it.

But that is not the worst. If the justification of exemplary punishment is not to be based on dessert but solely on its efficacy as a deterrent, it is not absolutely necessary that the man we punish should even have committed the crime. The deterrent effect demands that the public should draw the moral, ‘If we do such an act we shall suffer like that man.’ The punishment of a man actually guilty whom the public think innocent will not have the desired effect; the punishment of a man actually innocent will, provided the public think him guilty. But every modern State has powers which make it easy to fake a trial. When a victim is urgently needed for exemplary purposes and a guilty victim cannot be found, all the purposes of deterrence will be equally served by the punishment (call it ‘cure’ if you prefer0 of an innocent victim, provided that the public can be cheated into thinking him will be so wicked. The punishment of an innocent, that is , an undeserving, man is wicked only if we grant the traditional view that righteous punishment means deserved punishment. Once we have abandoned that criterion, all punishments have to be justified, if at all, on other grounds that have nothing to do with desert. Where the punishment of the innocent can be justified on those grounds (and it could in some cases be justified as a deterrent) it will be no less moral than any other punishment. Any distaste for it on the part of the Humanitarian will be merely a hang-over from the Retributive theory.

Back when I read this I was quite naive about how easily or often those in power in modern nation states would be willing to “fake a trial.” I read Lewis’s analysis as purely philosophical or intellectual. I didn’t think the theory would ever actually be practiced.

But here we see C. S. Lewis was a prophet. What do we need in order to justify a world “anchor”? We need more Hitlers. At least, we must have such Hitlers if we are going to keep the pretense of democracy. The people have to be continually frightened into willingness to being made inter-generational debt slaves in order to fund the anchor. Every hesitation to launch a punitive strike needs to be considered another “Munich moment.”

Lies aren’t an accident in American hegemony; they are the essence of it.

Assad is regarded as guilty because he must be guilty for us to attack him and show how we are a source of “stability” in the world. International “norms” must be violated so we can demonstrate that we enforce and uphold them.

But, with Cohen’s fulfillment of Lewis’ critique we now have data that can improve on that critique. Lewis said that the deterrent theory allows the state to portray an innocent man as guilty. But that is not enough. In order to give the public a clear moral lesson, we also need to fake the innocence of guilty men. Some suspect this explains some aspects of the George Zimmerman trial. Whether or not that is the case, it certainly is what Cohen is willing to do for the sake of justifying an attack on Syria:

The hesitancy since the chemical attack has highlighted a lack of U.S. leadership throughout the Syrian conflict. The just cause of rebels fighting the 43-year tyranny of the Assad family was never backed by arming them; and when Islamist radicals moved into Syria, their presence was used to justify the very Western inaction that had fostered their arrival.

While Cohen’s first lie is the pretense we have proven knowledge that we don’t really have, here he is just making stuff up. There was never an actionable moment where we could have armed a mythical faction of pure, democratic, secular rebels and prevented the black hats from “moving in.” This is nonsense. The fact is that, in order to aid the rebels the CIA had to work with the Muslim Brotherhood. This has been going on for more than a year–at least. It is unlikely there was any way to arm only the “good guys” by this method.

(As in the case of Syria, if Cohen was serious about his claims regarding the rebels then he would loudly condemn US/NATO action in Libya which we have given over to Al Qaeda as their happy hunting ground. How are we going to trust an “anchor” that has already lied to us and left a region in such a hellish state by empowering terrorists? Cohen doesn’t want to think about it and doesn’t want us to think of it. As with Iraq, all blame is put on the American people for doubting the US interventionists and none on the interventionists for either deliberately abusing our trust or else just being so incompetent and dangerously stupid that we should never trust them again.)

Beside all this, Assad’s cruel repression has almost certainly been felt most strongly by Syria’s Sunni majority who have been forced to endure a secular regime that allows freedom of religion. The rebels “just cause” and Sunni theocracy are not as far removed as Cohen wants his readers to believe.

The deterrent theory of punishment is virtually the only theory that is ever invoked in foreign affairs. This makes sense since the US works with immoral regimes all the time for the sake of some alleged greater good. The traditional view of justice is not permitted on the scene–except to hide the bankrupt morality of the deterrent theory, just as Lewis predicted.<>yandex статистика а

The post The cry for American world “leadership” shows us that C. S. Lewis was right about punishment appeared first on Kuyperian Commentary.