Although it can be misleading to seek the meaning of commonly-used words and expressions in their etymological origins, in the case of liberalism, the linguistic connection with liberty is all too obvious. The promise of liberty is an attractive one that holds out the possibility of living our lives as we see fit, free from constraints imposed from without. We simply prefer to have our own way and not to have to defer to the wills of others.

Yet even the most extensive account of liberty must recognize that it needs to be subject to appropriate limits if we are not to descend into a chaotic state of continual conflict, which English philosopher Thomas Hobbes memorably labelled a bellum omnium contra omnes, a war of all against all.

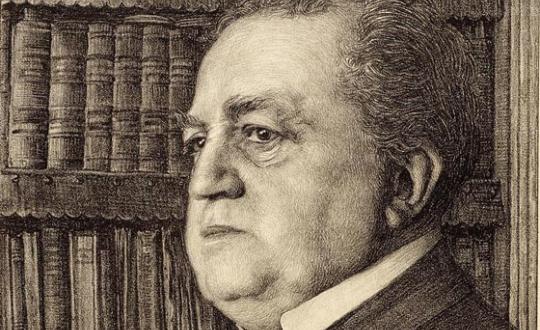

Here I propose to compare two approaches to liberty, viz., those of liberalism and of the principled pluralism associated with the heirs of the great Dutch statesman and polymath, Abraham Kuyper. Although each claims to advance liberty, I will argue that the Kuyperian alternative is superior to the liberal because it is based on a more accurate appraisal of human nature, society and the place of community within it.

Arising in the context of an early modern repudiation of ancient, and seemingly outmoded, customs and mores, liberalism proposed to anchor human community in rational principles oriented around the self-interest of sovereign individuals. From Locke to Rawls the liberal project has sought to liberate public life from the particularities of the “thick” accounts of reality rooted in the ancient religious traditions. Why? Because these had apparently proven hopelessly divisive in previous centuries, engendering nearly continual warfare from Luther’s initial efforts at reforming the church 500 years ago to the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

Better, it was assumed, to anchor political order, not in a highly disputable claim of divine revelation, but in principles capable of being affirmed by all. Such principles would have to be rooted in a rationality whose only underlying assumption would be that individuals pursue their own interests as they themselves understand them.

Liberalism is thus more than just about liberty. Even in its mildest form it assumes that community is rooted in the collective wills of its individual members, thereby privileging the voluntary principle, that is, the belief that human flourishing depends on the free assent of sovereign individuals to their multiple obligations. The liberal project represents an effort to address the central dilemma of human life famously summed up by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the following maxim: “Man is born free but is everywhere in chains.”

Our very survival as a species in the face of hostile forces of nature depends on our ability and willingness to co-operate with each other for common purposes. If we do not do so, we are doomed at best to poverty and at worst to death. Nevertheless, in so far as we are interdependent, our individual wills are necessarily constrained by the rules we draw up to facilitate this co-operation. This is the paradox that Rousseau tried to address in his own proposals for political order. Although Rousseau, in his Social Contract, took these ideas in a superficially liberal direction, his recipe has definite totalitarian implications, thereby threatening to crush the very diversity that makes politics necessary and indeed possible.

According to the late British political scientist Sir Bernard Crick, politics is all about the peaceful conciliation of diversity within a particular unit of rule. What is meant by this diversity? Richard Mouw and Sander Griffioen identify three basic types: (1) directional or spiritual diversity, viz., the plurality of ultimate beliefs that bind particular communities but are potentially divisive of the larger body politic; (2) contextual diversity, viz., the diversity of customs and mores that come from people living together in local communities that are relatively isolated from each other; and (3) associational diversity, which might better be described as societal pluriformity, viz., the plethora of communal formations characterizing a mature differentiated society. While liberalism represents a longstanding effort to address all three kinds of diversity, for our purposes we shall examine its relationship to numbers one and three, viz., directional diversity and societal pluriformity. Although these two kinds of diversity are logically distinct, any effort to address one inevitably affects the other as well.

An obvious way in which these two types of diversity intersect can be seen in the often vexing church-state issue. If one is an unbeliever, one is unlikely to accord the gathered church a distinct status apart from the state except as a voluntary association of like-minded believers. In denying the authority of the gathered church institution, the political order formed out of this belief will nearly inevitably subordinate it to the political authority of the state, along with a variety of other voluntary associations, such as the Boy Scouts, the local garden club and little league baseball. This, of course, has profound implications for the protection of religious freedom, which is thought to belong only to individuals, and not to the institutions that have shaped them. A liberal worldview privileging individual rights, a particular manifestation of directional diversity, has effectively denied societal pluriformity, or Mouw and Griffioen’s associational diversity.

Crick believes that ordinary politics requires the tolerance of multiple truth claims. While he is undoubtedly empirically correct in his observation, we must be wary of attaching a normative character to this reality because it may effectively mask the extent to which a particular conception of church-state relations is itself rooted in a religiously-based worldview. And, if so, we will need to be prepared to admit that not all pluralisms are created equal.

Part 2: The Church as Voluntary Association

Let’s not forget the link to the “libertines” which is the philosophy of the libertarians of today. You can be a christian, or you can be a libertarian, but you really can’t be both. The Bible is not a libertarian manifesto, God has rules and we are bound to follow them.