Why Christians Should Read Virgil

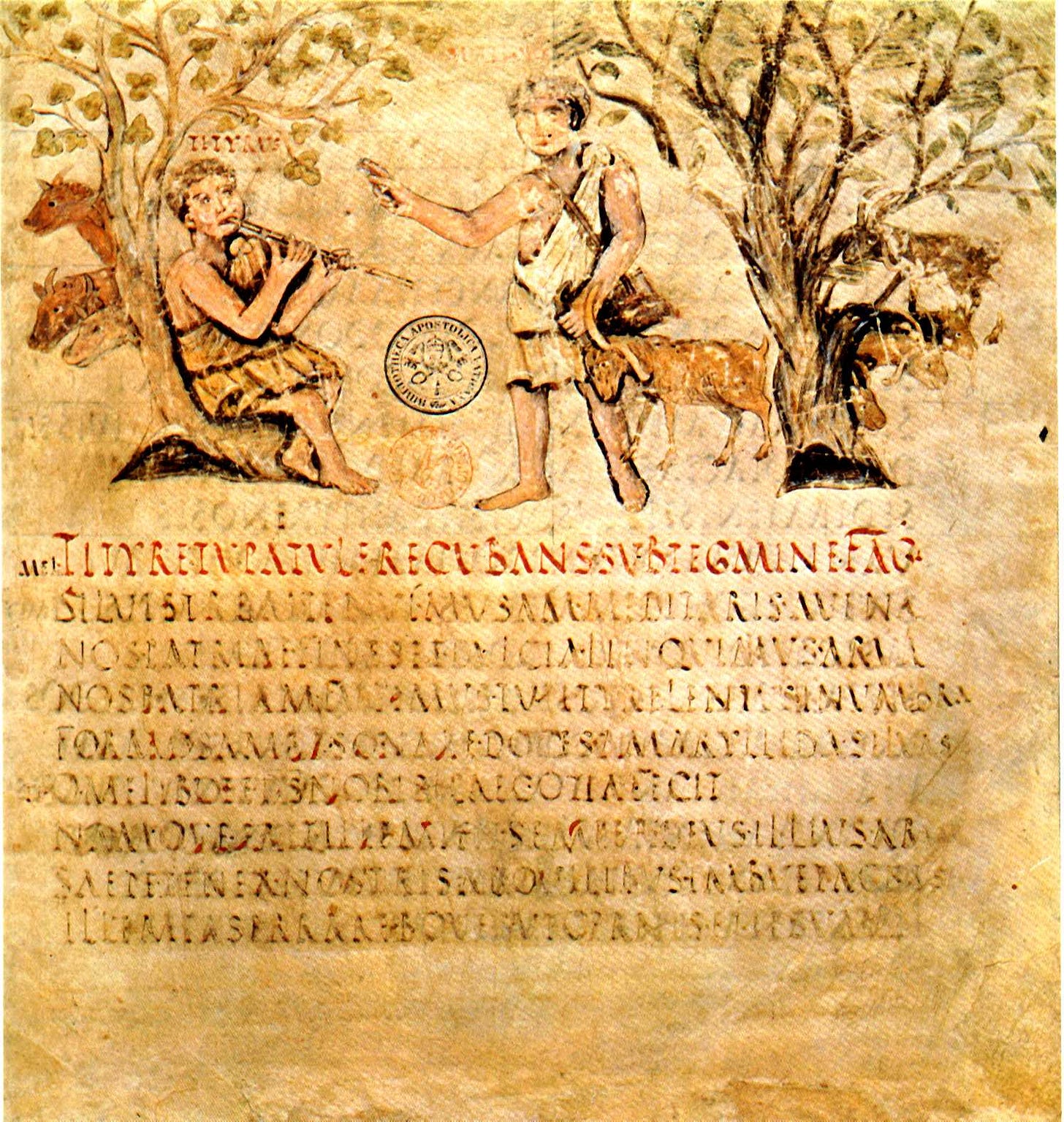

The works of Virgil are often associated with painful assigned readings and Latin lessons, but a careful reading of this Roman poetry can help the modern Christian understand the first century context of the Christian Church. The poetry of Virgil’s Eclogues, Georgics, and the Aeneid represents a new shift in classical literature, away from tragedy in the Greek sense and toward the expectation of a new golden age.

Virgil Writing on the Eve of Christ’s Birth

Writing in the period following the death of Julius Caesar (44 BC) and during a time of unrest and civil war, Virgil’s initial poetry longs again for peace. Recognizing that the power of the Caesar was not enough to provide a stable future, the poetry focuses on a greater motif of the goodness of creation and nature. Virgil’s agriculture poetry serves two purposes in that it remains relatable to their common life and points to the perfection of the original creation. In relating to his fellow Romans, Virgil’s pastorally lines about husbandry and agriculture remind us of those used a few decades later by the triumphalist born of a virgin who hailed from the town of Nazareth.

The parables of Virgil and Jesus offer accessible wisdom for a generation caught amidst uncertainty and turmoil – hope for people crushed by the weight of the Roman Empire. The use of pastoral parables by Virgil and Jesus are also aimed at the same goal of bringing forth the image of creation. Both the Yahweh of the Jews and the Jupiter of Olympus offer a perfect garden-city where man ought to return. Restoring paradise or returning to Eden is the cultural lens of these pacific scenes of simple farming life. With a clear common cultural context on this issue, it is no surprise that Western culture has kept Virgil in the realm of their own hagiography.

The Messiah’s Garden-City in Virgil’s Poetry

Virgil’s Eclogues represent the first and prophetic part of the poet’s commentary on the political future of Rome. It is here again that Western thinkers picked up on the more messianic triumphalism of Virgil’s writing. The golden age of Rome, according to Virgil’s fourth Eclogue, was to be brought about by the birth of a savior. The following lines represent a messianic view of the man to come:

Yet do thou at that boy’s birth,

in whom the iron race shall begin to cease,

and the golden to arise over all the world,

holy Lucina, be gracious; now thine own Apollo reigns. (2. 8-11.)

It has been speculated whether Virgil may have been influenced by Jewish or Eastern thinkers in putting forward a prophecy similar to those made by Isaiah. Although there is not evidence to suggest that Virgil interacted with the Hebrew writings or even that the later Gospel writers interacted with Virgil’s poetry. Virgil’s messianic verses have caused Christian thinkers throughout the centuries to consider the poet a type of prophet for Christ. The timing of this prophecy is perhaps one of the reasons Dante Alighieri employs Virgil as a “guide” in his own poetry in the Divine Comedy.

Virgil, Dante and the boatman, Phlegyas

Rome’s Version of “Thy Kingdom Come”

While the prophecy of Isaiah would predict the coming of a Messiah whose, “Kingdom would have no end” (Isaiah 9:7), Virgil’s later work would reveal Jupiter putting forth Rome as the “imperium sine fine” or the endless empire. The hope of Virgil’s triumphalism is the imminent realization of this savior to usher in the new world, albeit through Virgil’s personal identification with Roman patriotism, morality, and heroism.

Expecting that the Golden Age of Rome is at hand, Virgil is called to write his great epic The Aeneid. The story is again a garden story. The story of noble and perfect beginnings that Rome now longs for under their current emperor. In a triumphalist sense, Aeneas is to Adam what Octavius is to Jesus. The Rome that was once Eden is to be restored to wealth, virtue, and peace under the rule of the endless empire. There is in this climax a certain parallel between the Pax Augustus and Pax Christi.

Hail! King of the Jews!

Their parallels ultimately converge as St. John the Baptist announces the coming of Christ’s Kingdom. Christ’s role as the “Son of God” serves as a direct challenge to the narrative of Virgil with the Roman Emperor as “son of God.” This doctrine coupled with the Christians’ commitment to only worship the true emperor, is the source of the conflict between Rome and the Christian Church. Christ’s imperial reign begins at the edict of Pilate as this title was hung above his dying body: “Jesus Of Nazareth The King Of The Jews.” The Roman world hungry and ready for the Kingdom of the “Son of God” then follows the Roman Centurion, who at the foot of the cross transferred that title from Rome to Jesus.

Julius Caesar, Augustus, Tiberius, and subsequent Roman emperors were regularly referred to as “son of God” (divi filius)

Reading Virgil allows us to see how the Romans of the first century would have received Christ’s ministry and understood the reality of his kingdom. A hearty reminder that the sentimental and personalized Jesus born out of our modern age would make little sense to the ancient reader of the Gospels. Christ’s ascension was a clear picture of his enthronement and his reign from the right hand of the Father. The Kingdom really is now. The hope and longing of all of history is realized in the present reality of the reigning King who has and is making all things new.

Recommended Resources for Reading Virgil

Deep Comedy: Trinity, Tragedy, & Hope In Western Literature by Peter Leithart

The Cambridge Companion to Virgil by Charles Martindale

Virgil’s Gaze: Nation and Poetry in the Aeneid by JD Reed

Virgil: A Study in Civilized Poetry by Brooks Otis

Virgil: Eclogues (Cambridge UP)

Virgil: Georgics (Cambridge UP)

Virgil: The Aeneid (Cambridge UP)

C. S. Lewis’s Lost Aeneid: Arms and the Exile by AT Reyes

The post Why Christians Should Read Virgil appeared first on Kuyperian Commentary.