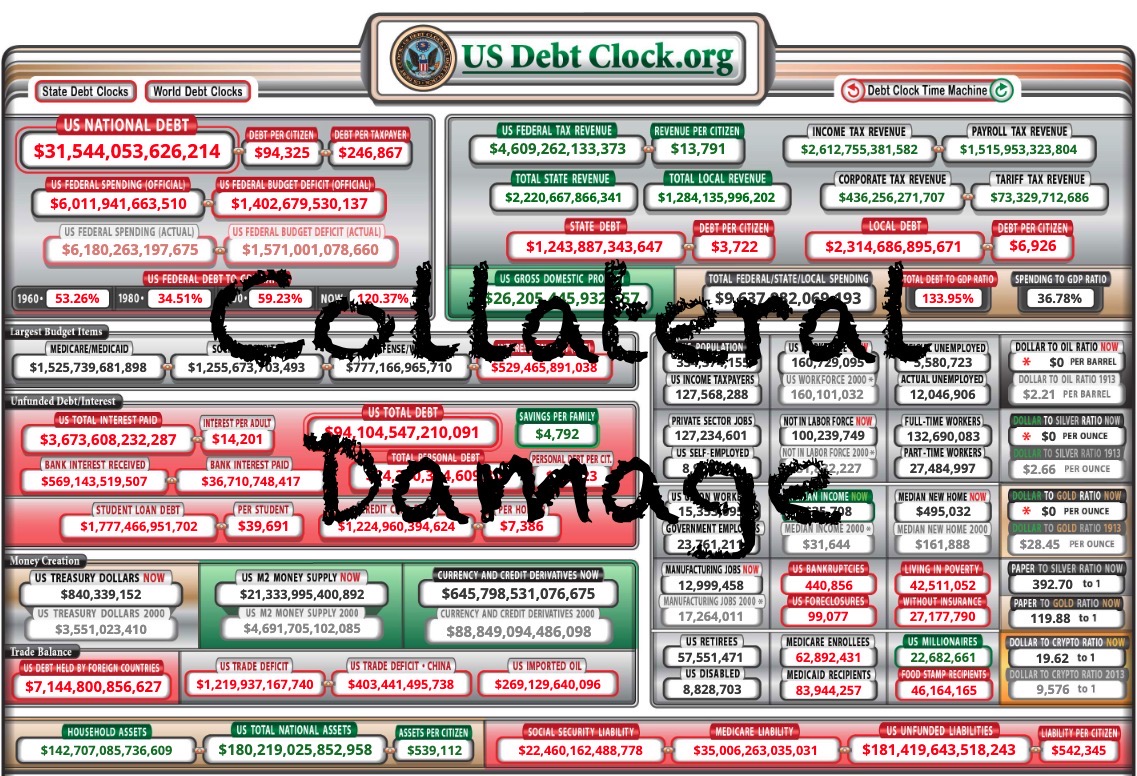

Debt makes the world go ‘round. At least it does now. Somewhere along the way in American and global history, our economic systems have moved from debt being a part of the system to debt being their foundation. If all the debt was paid off tomorrow, our system would collapse. (For a simple explanation of this, read this article.) In the spirit of keeping things moving, our government is accumulating debt at a record pace. As of February 2023, we are $31.5 trillion in debt, most held by the American government along with Japan and China holding significant amounts of our debt to prop up their currency. American citizens have joined the spending spree. Credit card debt has soared to almost $1 trillion. With citizens unwillingly (for the most part) being guarantors for the government and credit card companies encouraging borrowing while only paying the interest, borrowers feel free to spend prodigally. This is not sustainable forever, and those who back these loans willingly or unwillingly will feel the effects eventually.

On several occasions in Proverbs, Solomon warns his son, the king-in-waiting, about the foolishness of becoming surety for someone else’s debts (Pr 6.1-5; 11.15; 17.18; 20.16; 22.26-27; 27.13). Becoming surety is not loaning, borrowing, or investing money. In each of those cases, there is a possibility of a return on investment. Surety is securing someone else’s debt in a way that you take all the risk with no possibility of financial reward. Your friend wants to borrow money, doesn’t have the collateral to back up the loan, and you and your assets become collateral for the loan, the guarantee to the creditor that he will receive his money. If the friend falls on hard times or bails on his responsibility, you are left holding the bag … an empty bag.

So what? Why is this such a big deal? Why does he repeat himself on this matter several times? It goes to the overall purpose of his instruction. Solomon is teaching his son how to faithfully take dominion over the world as God commanded the original man (who, as you might know, failed in the task). Somehow, becoming surety for a “stranger” (a man who is outside of the boundaries of your authority) hamstrings that mission, causing you to fall short of the glory that God intends. (Glory is associated closely with dominion in Scripture. It is the rule with all of its accouterments that reveal its weight and beauty.)

Your possessions are both tools and products of your dominion activity. They are some of the glory that God has called you to cultivate. As you grow in wealth, your authority grows. Money is power, as it is said. Money is a form of or an expression of authority that is exercised on the world to reshape it. Wealth can build Solomon’s temple, or it can transform a system of justice (as George Soros seeks to do). Jesus connects money with authority in his parable of the talents or minas (Mt 25.14-30; Lk 19.11-27). The master gives a certain amount of authority to each servant in the form of money, and then he rewards the faithful servants with more authority while stripping the unfaithful servant of any authority. Though wealth is not the only means of dominion, it is one of the means of building the kingdom of Christ. As in the parable, God grants some more than others, but everything is to be invested wisely to produce more.

What happens if you submit these tools of dominion into the hands of a creditor with no possibility of return? You stand to lose your God-given power to effect change to re-order the creation. All of that power is now in the hands of a creditor who will use it for who knows what. You risk the gifts of God for the completion of your mission with no possibility of a profit. That is unwise.

This foolishness reflects a deeper principle that runs, not only through the warnings about surety, but also through all of the instructions concerning authority. That principle is, you are not to take on responsibility where God has not given you authority. When you become surety for another man’s debt, you are taking on the responsibility of his commitments without having any authority to control the situation. God doesn’t give responsibility where he does not give authority. If he commands you to do something, then that means you have the authority to do it. But your authority is limited, bound by God’s commands and providence. Assuming responsibility and commensurate authority that you do not have is a fool’s errand.

If you take on the responsibility to fix someone else’s life, you’re overestimating your authority. You may encourage, exhort, rebuke, cajole, or aid him in other ways, but you don’t have authority over him that can make him do anything. You are not responsible for the commitments other people make. You can’t become surety for them emotionally, psychologically, or financially. You can be concerned, but where concern becomes distorted into frustrated anxiety that feels the urge to make him do what you want, you have crossed the line. You have assumed a God complex. Care for him. Counsel him when you can. But don’t assume responsibility where you don’t have authority. Those who do so lack sense (Pr 17.18) and are playing the fool.