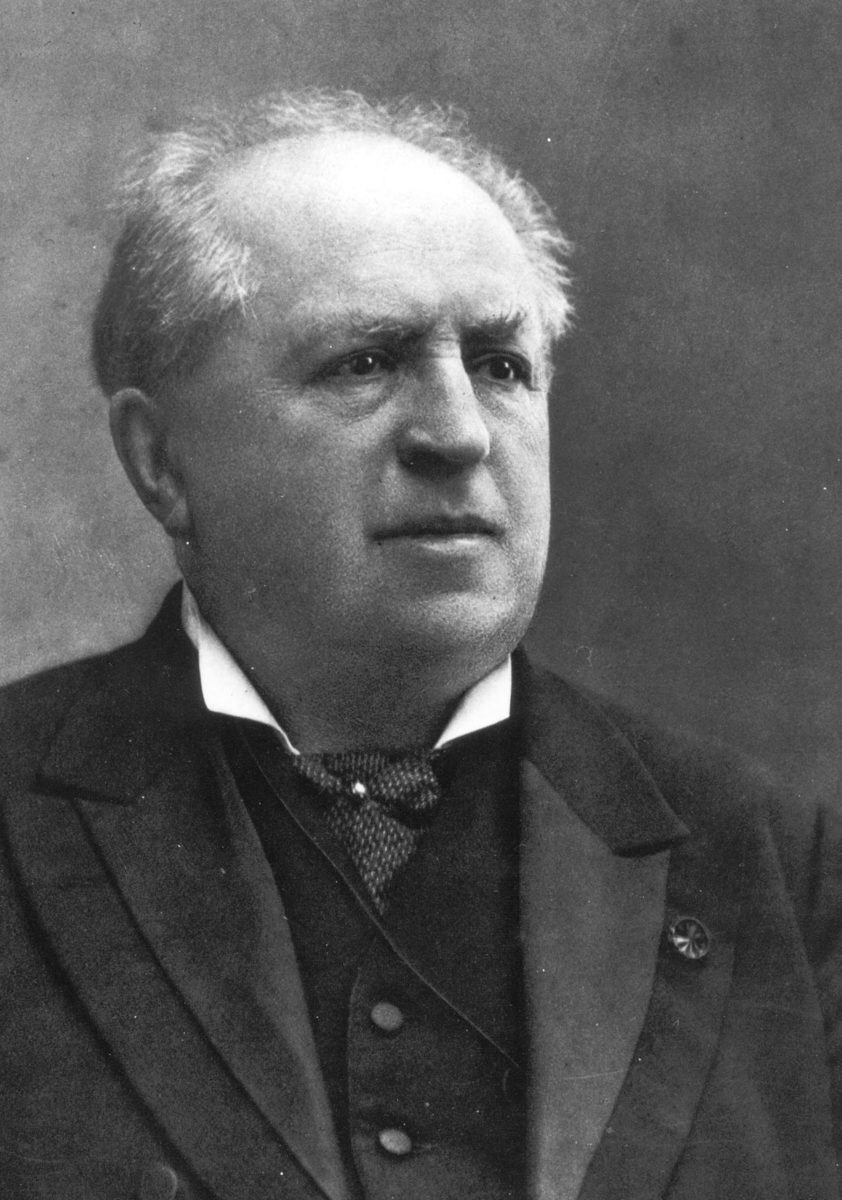

This is the second part of a six part article series on Abraham Kuyper’s Lectures on Calvinism. He gave these lectures at Princeton Theological Seminary over a series of days in October 1898. Happy International Abraham Kuyper Month!

Religion is For God

In this second lecture, Kuyper argues that Calvinism has a religious energy that other theological camps do not. This energy is found in how Calvinism places God and God’s glory at the center of all religious life. This energy restores the true nature of religion and this restoration in turn sets out the full task of man before God.

What is this religious energy in Calvinism? It is that all of the Christian religion must be for God. Kuyper says, “The starting point of every motive in religion is God and not Man” (p 46). God should be our primary and ultimate goal. We must love and worship God for His own sake, not because we are trying to get a reward out of Him. Kuyper says this is our goal: “…to covet no other existence than for the sake of God, to long for nothing but the will of God, and to be wholly absorbed in the glory of the name of the Lord, such is the pith and kernel of all true religion” (p 46). The true demand of the Christian life is that we must spend all our energy following God’s will.

Placing God at the center of the Christian life undermines many of the religious errors in man. Kuyper says, “Religion for the sake of man carries with it the position that man has to act as a mediator for his fellow-man. Religion for the sake of God inexorably excludes every human mediatorship” (p 48). Kuyper then glances at Augustine of Hippo and offers a critique of this early church father. While Augustine was accurate on many theological things, Kuyper points out that Augustine still remained “The Bishop.” This title seems to imply that Augustine was standing between Man and God, but really Augustine was just a man like other Christians.

Kuyper says, “If, on the contrary, the demand of religion is that every human heart must give glory to God, no man can appear before God on behalf of another. Then every single human being must appear personally, for himself, and religion achieves its aim only in the general priesthood of believers” (p 48). In recognizing all Christians as priests before God, Kuyper and Calvin recover the true spirit of Christian liberty. Kuyper says it this way, “Only where all priestly intervention disappears, where God’s sovereign election from all eternity binds the inward soul directly to God Himself, and where the ray of divine light enters straightway into the depth of our heart–only there does religion, in its most absolute sense, gain its ideal realization” (p 49).

Kuyper then pushes this religious fervor to the edges of life. He says, “God is present in all life, with the influence of His omnipotent and almighty power, and no sphere of human life is conceivable in which religion does not maintain its demands that God shall be praised, that God’s ordinances shall be observed, and that every labora shall be permeated with its ora in fervent and ceaseless prayer” (p 53). When man is focused on God as the goal of all religion then this sweeps up all of man’s life into a life of prayer and worship for God. In Calvinism, all of man’s work becomes an act of doxology to God.

Kuyper summarizes this point: “Wherever man may stand, whatever he may do, to whatever he may apply his hand, in agriculture, in commerce, and in industry, or his mind, in the world of art, and science, he is, in whatever it may be constantly standing before the face of his God, he is employed in the service of his God, he has strictly to obey his God, and above all, he has to aim at the glory of his God” (p 53).

The True Church

Kuyper then takes this vision–the Christian religion being for God–and he applies this to the Church herself.

Kuyper first looks at the nature of salvation. He says that salvation as a work of God will be a complete and total work. This is not universalism (where everyone will be saved) but it is a universal work. Kuyper says it this way, “To be sure, many branches and leaves fell off the tree of the human race, yet the tree itself shall be saved; on its new root in Christ, it shall once more blossom gloriously. For regeneration does not save a few isolated individuals, finally to be joined together mechanically as an aggregate heap. Regeneration saves the organism, itself, of our race” (p 59). Ultimately, our salvation is not about us but about God and His glory and as such this means that God will bring about the salvation of His creation. All creation must worship Him alone and so God’s glory necessitates a work of salvation that reaches all creation.

Given that religion is for God, He will not allow anyone or anything to get in the way of right worship for Him. Kuyper condemns errors in other denominations, particularly Roman Catholicism (what he calls Romanism) which try to put something between God and His people: building structures, confessionals, priests, etc. When Christians are called by God, He calls them directly to Himself. So while in this life, we are on a pilgrimage, this is not a trip that starts in a far distant country. Rather, Kuyper describes our pilgrimage as one that starts at the door and we are walking into the Sanctuary (p 61).

This excludes the idea of an Institutional church dispensing grace out to the weary traveller on his way to salvation. There is no partial salvation for believers. Salvation is a one time event that takes the person before God. God does not need extra help from an institution to save us. Kuyper says this means that there is no salvation after death because a Christian is already saved in Jesus. This also excludes masses for the dead or teaching that after death people can be saved. The church does not help in the process of salvation. Salvation is a full and pure work of God.

Kuyper then turns to explain what the church is. He says, “For Calvin, the Church is found in the confessing individuals themselves–not in each individual separately, but in all of them taken together, and united, not as they themselves see fit, but according to the ordinances of Christ” (p 62). The Church is found in the people who make up the body of Christ not an institution or hierarchy.

Kuyper says, “But if the Church consists in the congregation of believers, if the churches are formed by the union of confessors, and are united only in the way of confederation, then the differences of climate and of nation, of historical past, and of disposition of mind come in to exercise a widely variegating influence, and multiformity in ecclesiastical matters must be the result” (p 63).

Here Kuyper gives a most robust defense for all the diverse ways that Christians have worshipped God over the years and centuries. Different congregations will worship with different music and different liturgies and different languages because the church is made up of different people and different people groups. To try to claim that all churches must have the same liturgy or the same music or the same language is silly. God has planted His people in different times and cultures and places and so the Church will look different because of that. This is not a problem. This is a glorious feature of the gospel.

Kuyper correctly says, “The Church of Christ is not national but ecumenical. Not one single state, but the whole world is its domain” (p 65). This means that every tribe, tongue, people, and land must worship God and that worship service will include every language and music and liturgy imaginable because each congregation will do that with the gifts and talents that it has available.

Calvinism and the Practical Life

Kuyper then argues that this vision of right religion changes everything in our practical lives. He says, “[A Christian] is a pilgrim, not in the sense that he is marching through a world with which he has no concern, but in the sense that at every step of the long way he must remember his responsibility to that God so full of majesty, who awaits him at his journey’s end” (p 69). The fact that we owe God everything in our lives changes everything in our lives.

It is not just that we need to be invested in this life, but we must recognize how God is invested in the world as well. Kuyper describes God’s involvement in the world as the Ordinances of God. God has thought out the world and all its ways and we see this all around us in the various works of creation.

Kuyper writes, “So, there are ordinances of God for the firmament above, and ordinances for the earth below, by means of which this world is maintained, and, as the Psalmist says, These ordinances are the servants of God. Consequently, there are ordinances of God for our bodies, for the blood that courses through our arteries and veins, and for our lungs as the organs of respiration. And even so are there ordinances of God, in logic, to regulate our thoughts; ordinances of God for our imagination, in the domain of aesthetics, and so, also, strict ordinances of God for the whole of human life in the domain of morals” (p 70).

These Ordinances of God reveal the foundation for all our actions as Christians in the world. We are to imitate God’s care for the world in how we live in the world. We are not to separate ourselves from the world but to seek it out and embrace it.

Kuyper offers a wonderful critique of Anabaptism which is a growing problem in our own time. He says, “The avoidance of the world has never been the Calvinistic mark, but the shibboleth of the Anabaptist…They refused to take the oath; they abhorred all military service; they condemned the holding of public offices. Here already they shaped a new world, in the midst of this world of sin, which however has nothing to do with this our present existence” (p 73). BUt this Anabaptist vision is a faulty one. It tries to claim that God is not concerned about the world around us and so we should pull away and hide from it. Kuyper says the Anabapist tries to create two worlds: one for the Christians and one for the secularists. But Kuyper rejects that idea. God is personally invested in the world and He has established Ordinances for all of life. This means Christians cannot be faithful to God unless they move into the world in an effort to bring all the world into subjection to Him: music, art, farming, politics, philosophy, education, business, etc.

Kuyper says this about the Christian: “He feels, rather, his high calling to push the development of this world to an even higher stage, and to do this in constant accordance with God’s ordinance, for the sake of God, upholding, in the midst of so much painful corruption, everything that is honorable, lovely, and of good report among men” (p 73). The world was made by God and for God. This means the Christian must point everyone and everything to that God. It is all for Him.

Kuyper closes out this lecture, saying “Calvinism understood that the world was not to be saved by ethical philosophizing, but only by the restoration of tenderness of conscience. Therefore it did not indulge in reasoning, but appealed directly to the soul, and placed it face to face with the Living God so that the heart trembled at His holy majesty, and in that majesty, discovered the glory of His love” (p 77).