I recently had a student get injured. Not seriously so, but enough to warrant a few sick days. I told the student I wanted to pray for her, that God would heal her ailment. She responded, “Thanks, but instead please pray that I’ll be more faithful in having quiet times. I don’t think God has much interest in my body, but I know he cares about my soul.” I asked the student if she was able to do the readings from class while she was out. “Yes,” she said hesitantly, “I’ve been up to my eyeballs in Plato!”

Well over two millennia ago, Plato gave an analogy that helped shape much of Western philosophy going forward. Here’s the most famous (though, not best) interpretation of the allegory: There are people in a dark cave facing a wall. Behind the people is a fire and behind the fire is an opening to the outside world. In that world, people walk, talk, dance, live.

Inside the cave, however, the people can only watch their shadows. Having never seen the outside, “real” world, the cave-people foolishly think the dancing shadows are ends in themselves, actual things. They aren’t, of course; they’re only shadows, “receptacles.” Freedom, for Plato, is recognizing the ultimate vapidity and illusiveness of the material world. Physicality—“objects”—lie in the realm of mere opinion and shadow. It’s in the incorporeal, metaphysical world of forms that true life can be found.

Having just completed readings surrounding this interpretation of the cave illustration, I asked the student, “how has this view shaped the church, do you think?” Substitute “objects” with “creation,” “form-world” with “heaven,” and you start to see the origin of the disembodied world many modern Christians inhabit. A view that leads us to think that only the spiritual world is real, and God takes no interest in concussions or broken bones.

This view stands in stark contrast with the biblical understanding of physicality. In Genesis 1 we see a world made by God. It is good, indeed, very good. Sin enters the world and distorts this goodness, but never eradicates the Creator’s handiwork. Sin is like rust on a ship; it’s not integral to the structure of the object. The ship existed before there was rust and will exist after the rust is removed. Indeed, the removal of the rust will only make the ship more of a ship.

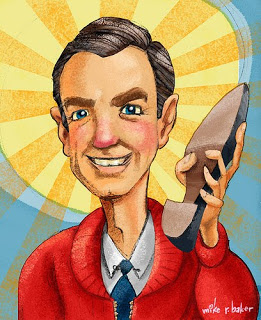

The Christian view of creation can be seen well in this exchange between Mr. Rogers and one of his neighbors, Jeff Erlanger:

Jeff was born with a tumor that left him bound to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. In the video, his handicap is pronounced and his young age only makes the disability more agonizing. Watching the episode, I can see why Plato wanted to understand the world as mere shadow. It explains and relativizes so much of the torment and agony of life. In understanding ourselves as more than physicality, there is hope. However, what do we lose when we understand ourselves as less than physicality? While Plato’s analogy can interpret our pain, I don’t think it can account for the beauty and dignity of this world.

Mr. Rogers no doubt sees Jeff’s brokenness, but he also sees his worth. To Jeff, he warmly sings, “It’s you I like. Every part of you. Your skin, your eyes, your feelings.” He saw the boy—the whole boy, body and soul—as real, as an end, as a creature. The wheelchair did not typify Jeff to Mr. Rogers. Nor was the “real” Jeff simply his spirit. In that moment, Rogers did what he did so often; he recognized and named the humanity in the other. Jeff was not a shadow to Mr. Rogers, he was real, he was worthy, he was loved.

When recounting so many of the difficulties of being handicapped, Jeff reminds us that there is such difficulty for everyone, those inside and outside of wheelchairs. Jeff knows we are all on a scale of brokenness, all in need of healing in myriad ways. So, in addition to praying for my student’s quiet times, I also prayed for her ailment, despite her earnest wishes. Because denying the goodness of our bodies won’t take away the badness. God did not place us in a cave, he placed us in a real-life neighborhood. The question is: will we see creation as a trick of the eye, or as a gift from the Creator? To do the former, ironically, is to choose to live in a cave of our own making. To do the later, however, is to be reminded of our Creator’s love for his creation when we hear Mr. Rogers’ song:

It’s you I like,

It’s not the things you wear,

It’s not the way you do your hair–

But it’s you I like

The way you are right now,

The way down deep inside you–

Not the things that hide you,

Not your toys–

They’re just beside you.But it’s you I like–

Every part of you,

Your skin, your eyes, your feelings

Whether old or new.

I hope that you’ll remember

Even when you’re feeling blue

That it’s you I like,

It’s you yourself,

It’s you, it’s you I like.