“Preach the word,” Paul charges Timothy (II Tim. 4.2); “devote yourself to the public reading of Scripture, to exhortation, to teaching.” (I Tim. 4.13) He is charged to be given to the Word in such a way that he will be able to guard against false doctrine, to entrust the body of doctrine received to faithful men in the congregation, and bring them up in leadership. The pastor is to be a minister of the Word, “able to teach”, and to fulfill that calling he must be a perpetual student of the Word. Scripture reading is one of the three essential acts of pastoral work described by Eugene Peterson in Working the Angles. In this post, we will converse with Peterson’s work as we briefly reflect on the ministry of the Word in pastoral work. a

Open Ears

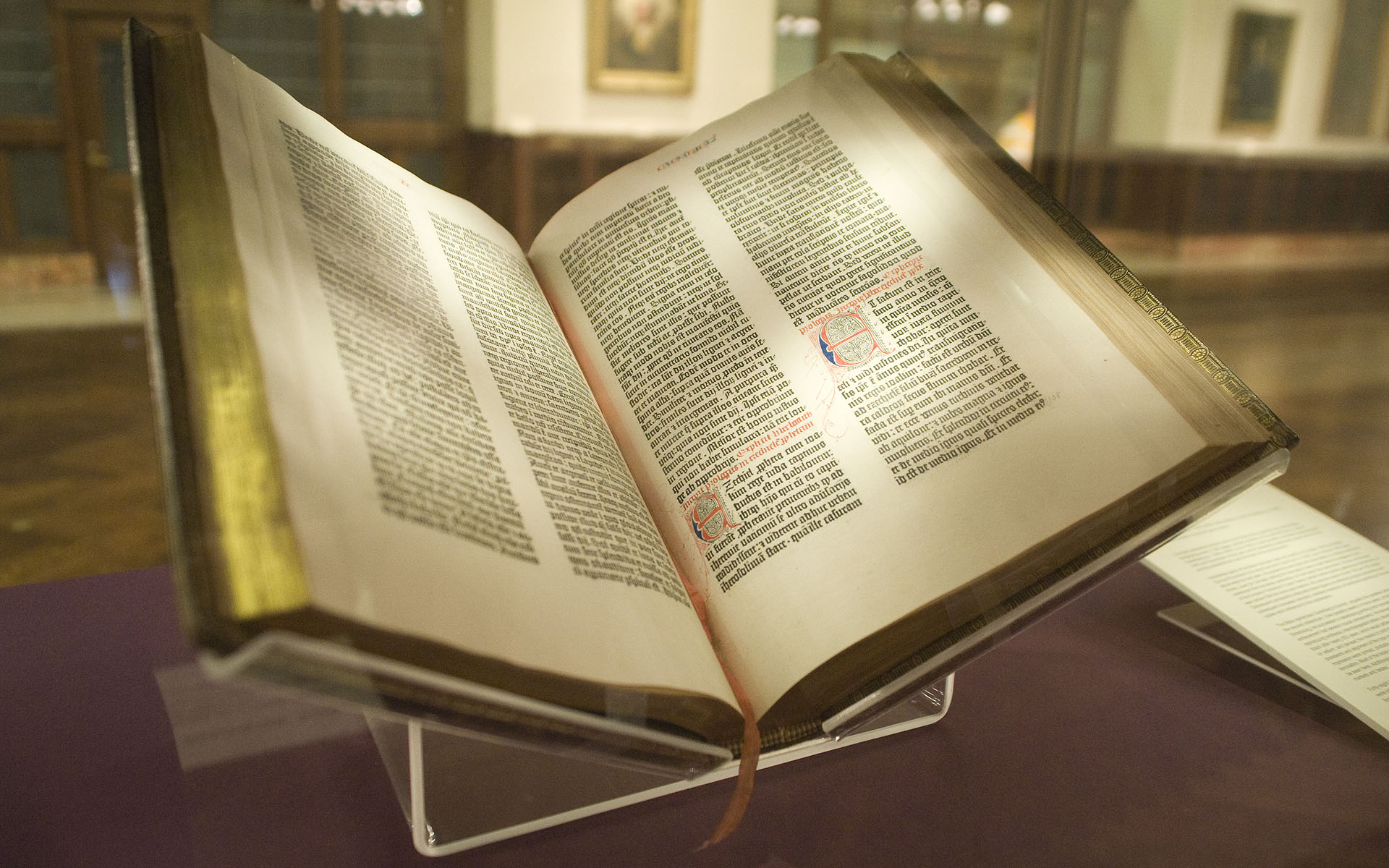

Pastors are called to the ministry of Word and Sacrament, yet it is in the midst of the pastor’s vocational study of the Word, Peterson warns, that the pastor may be at risk of abandoning his work: “in reading, teaching, and preaching the Scriptures, it happens: we cease to listen to the Scriptures and thereby undermine the intent of having Scripture in the first place.” We have become so accustomed, since the invention of movable type, to think of receiving the Word in visual terms that we can forget that our primary calling in regard to God’s Word is to listen. This mindset has had a significant impact on how the Church has understood the Word of God and its place and function in the community. “The Christian’s interest in Scripture,” Peterson says, “has always been in hearing God speak…” He calls pastors to “be analytically alert to the ways in which listening to the word of God slides off into reading about the word of God, and then energetically recover an open ear.” (Working the Angles, p. 87)

The shift from listening to reading has done much damage to the Church’s posture toward the Word. Prior to Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, texts were communal oral events, not data that was read silently and privately. Christians received God’s Word primarily through the ear in a communal setting, listening to Scripture read aloud in the Church. The text was, in this setting, a community-forming event. Instead, now Christians focus on an individualized reading of Scripture, a quiet and visual activity. This has led, Peterson argues, to an association of reading Scripture with schooling, “looking for information when we read rather than being in relationship with a person who once spoke and then wrote so that we could listen to what was said.” (p. 95) And this shift, he continues, helped shape our cultural self-understanding as consumers. A consumer comes to Scripture on his or her own, ready to “get something out of it.” As a consumer, Peterson says, “I am no longer listening to a voice, not listening to the God to whom I will give a response in obedience and faith, becoming the person he is calling into existence. I am looking for something that I can use to do a better job…” (p. 99)

The pastor must recognize this situation, and work to counteract it. “Pastors must not only notice; they must counterattack.” (p. 100) Pastoral work involves coming to Scripture with an open ear, not simply studying words on a page, but listening to the personal voice of God. And pastoral work involves opening ears, teaching those under the pastor’s care to listen, to place themselves under the personal, active Word of God. The primary and foundational encounter the Church experiences with Scripture, then, is in the public reading and proclaiming of the Word in the liturgical assembly. The liturgical listening and responding is to be programmatic and formative for the Christians relationship with God through His Word.

Contemplative Exegesis

In his commentary on Romans, Karl Barth describes Calvin’s approach to the text of Scripture:

“How energetically [Calvin] goes to work after he has conscientiously established ‘what is there’ to think the thoughts of the text after it, that is, to come to terms with it until the wall between the first and sixteenth centuries becomes transparent, until Paul speaks there and the man of the sixteenth century hears here…” b

Calvin was committed to a careful reading of Scripture, seeking to read and hear in a way that would lead to thinking “the thoughts of the text”, to thinking God’s thoughts after Him. Calvin’s exegesis was a slow, patient exegesis, letting God’s Word work on and in him. Calvin practiced what Peterson calls pastors to: a contemplative exegesis.

This kind of exegetical life requires “a drenching in Scripture.” The pastor needs “immersion in biblical studies… reflective hours over the pages of Scripture as well as personal struggles with the meaning of Scripture.” (The Contemplative Pastor, p. 20) The pastor is to study the Word as a living reality, the personal Word of God. He is to be shaped by the shape of Scripture, paying careful attention to the form of the story, letting that story shape his life and speaking that story into the community he is called to shepherd.

“Contemplative exegesis” will flow out into a public reading and preaching of Scripture that brings the people not just data or doctrine, but into an encounter with God through hearing His personal Word.

Studying God’s Word and proclaiming God’s Word to the Church involves a connecting of what will often seem to the congregation two disjointed realities: the Word of God as given in history, and the lives of the people lived now. “It is the unique property of pastoral work,” Peterson says, “to combine two aspects of ministry: one, to represent the eternal word and will of God; and, two, to do it among the idiosyncrasies of the local and the personal…” (Five Smooth Stones, p. 5) He is to preach in such a way so that the people will “know that their own lives are being addressed on their home territory.” (TCP, p. 21) This means a careful study of Scripture and an attentive “exegesis” of the local geography, history, and culture go hand-in-hand. The pastor is called to attention to “the particulars of creation and locales of redemption…” Gordon Lathrop is helpful here: “Attention requires me to see again the strangeness of the texts and the mystery of each person.” (The Pastor, p. 55)

- Like my last post, I must qualify: I’m writing about pastoral

work, but as an aspiring pastor, which is why I’m taking my cues here from someone with far more wisdom and experience than myself. (back) - Quoted in Richard Burnett, Karl Barth’s Theological Exegesis, p. 118. (back)