The passing of Queen Elizabeth II and her funeral liturgy gives Americans the unique opportunity to see the distance that exists between modern American versions of Christian worship and the worship as it was during the Reformation. The Church of England’s liturgical traditions are preserved in word and ceremony through their use of the Book of Common Prayer. Officially the English are bound to the reformed heritage of the Protestant Reformation in the historic 1662 edition. We could sneer at the stiltedness of such endeavors or perhaps even mock it based on the hypocritical participation of various royal and ecclesiastical apostates—yet I would charge that there is something special preserved here in two ways.

Gospel through Liturgy

The first is in the presentation of the Gospel through the liturgy. Since the service requires the use of Bible passages through its lectionary, more Scripture was read at this funeral than is typically read in most American Churches on any given Sunday. Even more, the Scripture lessons were more comprehensive in that portions were read from the Psalms, Gospels, and Epistles. Without the established tradition of the prayer book liturgy, who could say which Scripture (if any) might be read at a state funeral. Yet here the words of our Lord through St. John and St. Paul are clearly presented for the entire onlooking world to hear and “it shall not return void.” (Isaiah 55:11)

Death at a Funeral

A funeral with the casket in full view is similar to the imagery of the Lord’s table. Jesus offers the Lord’s Supper as part of Christian worship to commemorate his death. Therefore, when Christians continue to remember the last supper with bread and wine they are bringing to mind the death of Jesus. In addition to the imagery of the meal at a table, Christian tradition has also brought the Lord’s table to represent a type of ancient sepulcher. Early Christians burying their dead would not have dug a hole, but placed them upon the raised platform in a tomb. Traditions around eucharistic tables reflect this in their use of linen coverings, which were also used as shrouds for the dead. Another tradition that points to the Lord’s Table as a funeral image is the frequent engraving of five crosses on the surface of the table to represent the five wounds of Christ, who was laid upon the sepulcher. Additionally, we see as early as the 3rd century that church tables were constructed over the tombs of the martyrs. a Only a few example needs be offered, but many more examples can be drawn in the various traditions and ceremonies in the Church East and West.

Family Integrated Funeral

Drawing this connection between the Lord’s Supper and Funeral is helpful in that it shows how deformed modern views of the Lord’s Supper have become. American children are typically excluded from Lord’s Day services by the use of Sunday School. Most American churches additionally refuse to admit children to the table based on their misreading of St. Paul’s admonitions to examine oneself. (1 Corinthians 11:28)

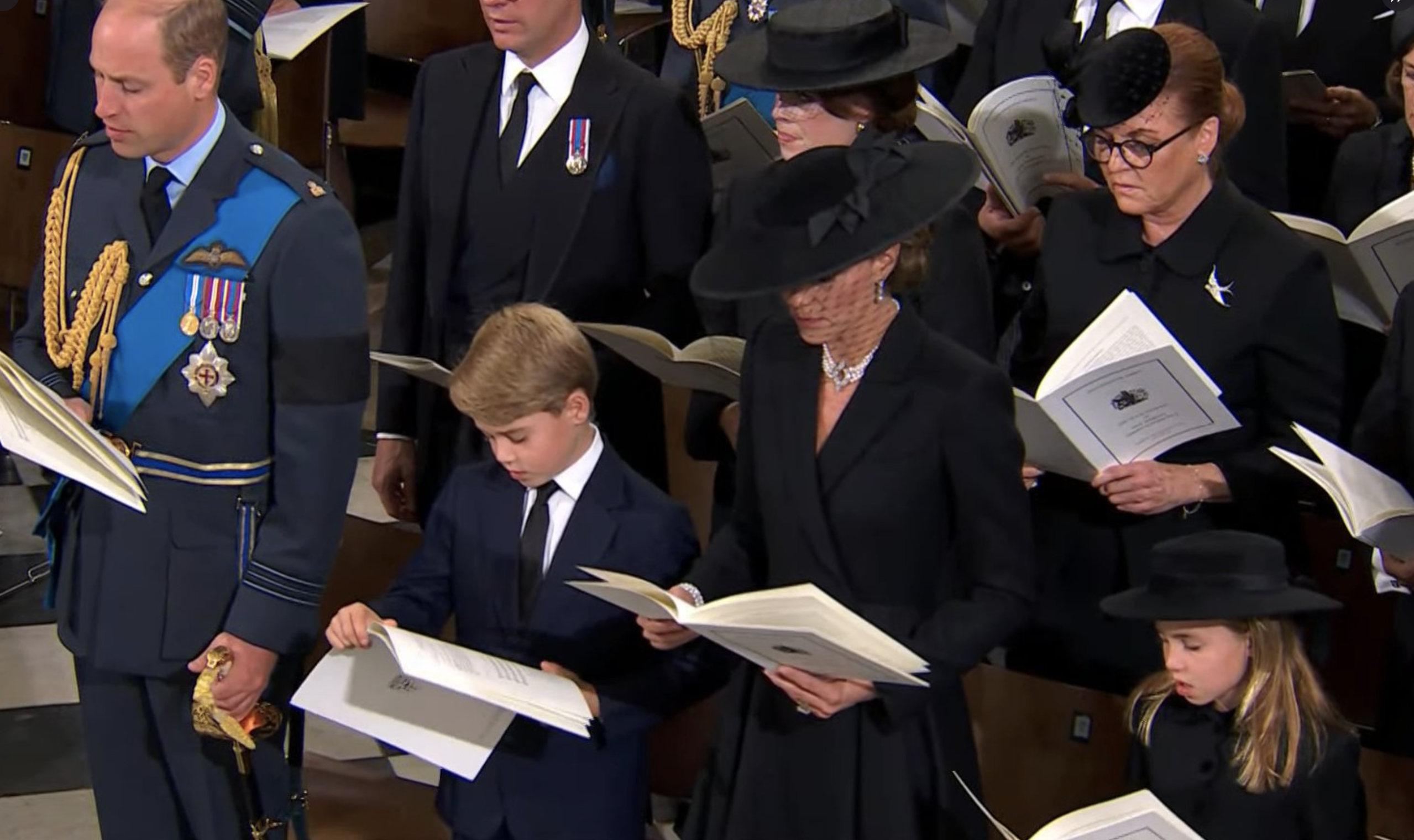

But when we look at the funeral of Queen Elizabeth II, we see the children of the royal family attending and participating in the service.

In fact, their absence would have brought shame upon their parents and scandal upon the entire family. People would have noticed if these children didn’t attend. Imagine for a moment how improper it would be for the royal children to be ushered away from the funeral and instead told to color a picture of the Queen or perhaps glue some macaroni, or learn a dumbed down version of “God Save the Queen.”

Instead Prince George, 9, and Princess Charlotte, 7, suited up in their Sunday best and followed along with the order of worship. They even walked in train with the casket.

This is formative behavior that the church needs for its children. In the Book, The Church Friendly Family, Rich Luck writes:

“Some parents feel it is completely within their rights to impose piano lessons and swimming practices on their children. But when it comes to religious things, they say they want their children to ‘make their own decision.’ But God tells parents they must impose a religious identity on their children—a specifically Christian religious identity. God says our children are His. He has claimed them from the beginning. We are to raise them up in His way. Beginning with baptism, we are to give our children to God and claim the promises He makes to and about them.”

- Liber Pontificalis attributes this to Felix I (back)