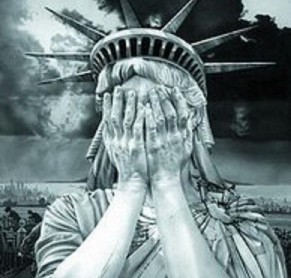

“Thus did Western Man decide to abolish himself, creating his own boredom out of his own affluence, his own vulnerability out of his own strength, his own impotence out of his own erotomania, himself blowing the trumpet that brought the walls of his own city tumbling down.” -Malcolm Muggeridge

If you could be dictator of America for one day, what would be the first thing you’d do to fix the country? In a recent interview, George Will gave a surprising response to this question, which I’ll paraphrase:

“I’d make every college student change their major to History and their minor to Contingency Studies.”

His point: America did not have to turn out the way it did. The Republic we inhabit is the result of bravery and revolutionary ideas, to be sure, but it’s also the result of an often under-appreciated element; namely, chance. In his new book, Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics is Destroying American Democracy, Jonah Goldberg takes this observation a step further. Not only is the freedom we enjoy a historical anomaly, it’s unnatural:

“Capitalism is unnatural. Democracy is unnatural. Human rights are unnatural. God didn’t give us these things, or anything else. We stumbled into modernity accidentally, not by any divine plan.”

If those of us who believe in providence dismiss his argument out of hand, we do so at our own peril. As Goldberg chronicles, for most of mankind’s history, we’ve lived a tribal, violent existence. That we now view the proverbial “other” with as little skepticism as we do is a feat of monumental proportion. A feat accomplished by what, you ask? Goldberg answers: money. Money made it possible for a person of one tribe to have an exchange with a person of another tribe that was mutually beneficial. The “other” in a free market isn’t just a competitor, he’s a customer.

Because the peace we have with one another now is incomplete and imperfect, it’s easy to view the current state of affairs with contempt. In the age of Trump, with identity politics being practiced by the Left and the Right, Goldberg sees the natural human propensity toward tribalism “coming back with a pitchfork.” We’re renovating the Republic with the sledgehammer of populism, knocking down institutions and norms at will, unmindful of which artifacts are structural and which are superficial, which are negotiable and which are load-bearing. Thus, the structural-integrity of the West has been compromised, perhaps irreparably, by those seeking to improve it. No, the current system isn’t perfect, but it’s better than an infinite number of alternatives that seemed inevitable a relatively short time ago.

There’s a famous story in which Benjamin Franklin is asked what sort of government the delegates at the Constitutional Convention are attempting to create, to which he responds, “A republic, if you can keep it.” Goldberg’s proposal for keeping the Republic lies not in specific policy proposals—he offers relatively few in the book—but in a disposition: gratitude.

Illustratively, two accounts of Aesop’s “golden goose” story are given in the book. In the first, the goose is killed out of rage because he wouldn’t—or couldn’t—lay more eggs for his owner. In the second, he’s killed by the owner so as to remove whatever mechanism is inside him that creates the gold. On a surface reading, the first telling blames passion while the second blames reason. The real culprit, however, is ingratitude, which can as easily corrupt the head as the heart.

The goose-killers weren’t grateful for the miracle of a golden egg laying goose—what an unlikely event! It’s simply not natural for a goose to lay golden eggs, and it’s simply not natural for man to live in the free, prosperous, peaceful society in which we find ourselves. No, we must not stagnate in the status quo, but neither must we take for granted the value of our free society. There has never been a better time to be alive—we’ve won the historical lottery, we should be grateful.

Another Form of Suicide

This brings me to my main problem with the book. Goldberg says on the first page that there is no God in his argument. He makes clear that he’s not an atheist, but neither does his reasoning depend on the existence of a deity. In a sense, I appreciate what he’s trying to do. He’s making a limited case for Classical Liberalism and wants the opportunity to persuade people of that argument without being tangled up in more thorny metaphysical debates.

By and large, I think his description of the situation in which we find ourselves will be compelling to those who don’t believe in a higher power. The historical, sociological, and psychological data backs up Goldberg’s argument that we’re prone toward tribalism and violence. Yet, the prescriptive portion of the book, built as it is on the notion of gratitude, is unintelligible in a godless universe. Yes, it’s good and right to be grateful for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but to whom are we grateful? Who receives our thanks? Does not gratitude imply a personal, transcendent “Other?”

Without such a being, our gratitude for the events of the past that brought us to the present becomes neutered into something like nostalgia. In Scripture, God’s covenant people are often called to look back, but they do so with their feet in the present and their eye toward the future. Looking to God’s actions in the past will encourage and ennoble his people toward steadfastness and faithfulness in those things God is calling them to do in the moment and in the moments to come.

Nostalgia, on the other hand, is an indulgent retreat to yesteryear; leaving the real present for a glossy, sentimentalized version of a past that likely never was. Nostalgia is an existential form of suicide. Gratitude leads to good works, bravery, and life. If liberalism is the result of chance, nostalgia is the best we can hope for. If it’s the result of divine providence, the gratitude for which Goldberg calls is not only possible, it’s necessary.

Likewise, belief in God will keep us from being paralyzed with fear. It would be easy to walk away from Goldberg’s book suspicious of any talk of “progress.” But Christians live under the rule of a city that is to come. In Scripture, we find the words of that city’s King, and in those words, we find the recipe for human flourishing in the here and now. Thus we can amend and tweak the structures of the West responsibly, as happened with women’s suffrage and the abolition of slavery. We look back with thanks, but we also march forward with hope.

The quote often attributed to Tocqueville is apropos, “America is great because America is good.” Goldberg is surely correct in his claim that man’s sinful nature is always ready to reappear. He’s also right to suggest that the “Lockean Revolution” has birthed the freest, most prosperous civilization in history. He’s wrong to think, however, that the free market and all that comes with it is enough to keep our nature at bay. Our liberal democracy is dependent upon a virtuous citizenry, a virtuous citizenry is depended upon gratitude, and gratitude is dependent upon one to receive our thanks, a Giver of all gifts, a King above all kings. If the West is to be saved, she’ll need a Savior.