Christianity Today recently published an article by Russell Moore titled, Bring Back Altar Calls, with the following subtitle: “They could foster the worst in evangelical spirituality. But the best of it, too.” Because the article is behind a paywall, I cannot assess the author’s argument, but I will take the occasion to look at the altar call because it is something with which I grew up, at least in part. No, not at the Orthodox Presbyterian Church congregation my parents started with another family in Wheaton, Illinois, when I was a small child. The OPC represents a rather pure form of Old School Presbyterianism, which took a dim view of New Measures revivalism in the 19th century. Worship in our congregation was based on the 1961 Trinity Hymnal, along with the use of traditional liturgical forms such as the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, the Gloria Patri, the confession of sin and assurance of pardon, and the weekly reading of the Ten Commandments. We sang metrical psalms from the 1912 Psalter of the former United Presbyterian Church in North America.

During spring and summer holidays, however, our family would visit my grandmother and other relatives in small-town southeast Michigan, where we would often remain for weeks at a time. On sundays we worshipped at an independent Baptist church where my mother had been converted to the faith in her late teens and where my parents were married several years later. Worship was something of a haphazard affair. There was no real order of worship laid out in a bulletin. The presiding minister would simply announce the hymns as we went along. These hymns were largely the revival hymns developed following the Second Great Awakening at the turn of the 19th century. The Bible was the King James Version, and everyone brought their own copy along. Many sermons focussed on the end times reflecting a dispensational interpretive framework.

Near the end of every service, after the scripture readings and sermon, there was an altar call. The minister would ask the parishioners to close their eyes while the organist played the strains of Charlotte Elliott’s Just As I Am Without One Plea, an apparent borrowing from the Billy Graham crusades. Then he would invite people to come forward to dedicate or rededicate their lives to Jesus Christ. Either that or he would ask people to raise their hands if they needed prayer. After nearly six decades, the memories of this experience have faded. Yet I still recall recognizing that this was quite different from what we did in our home church.

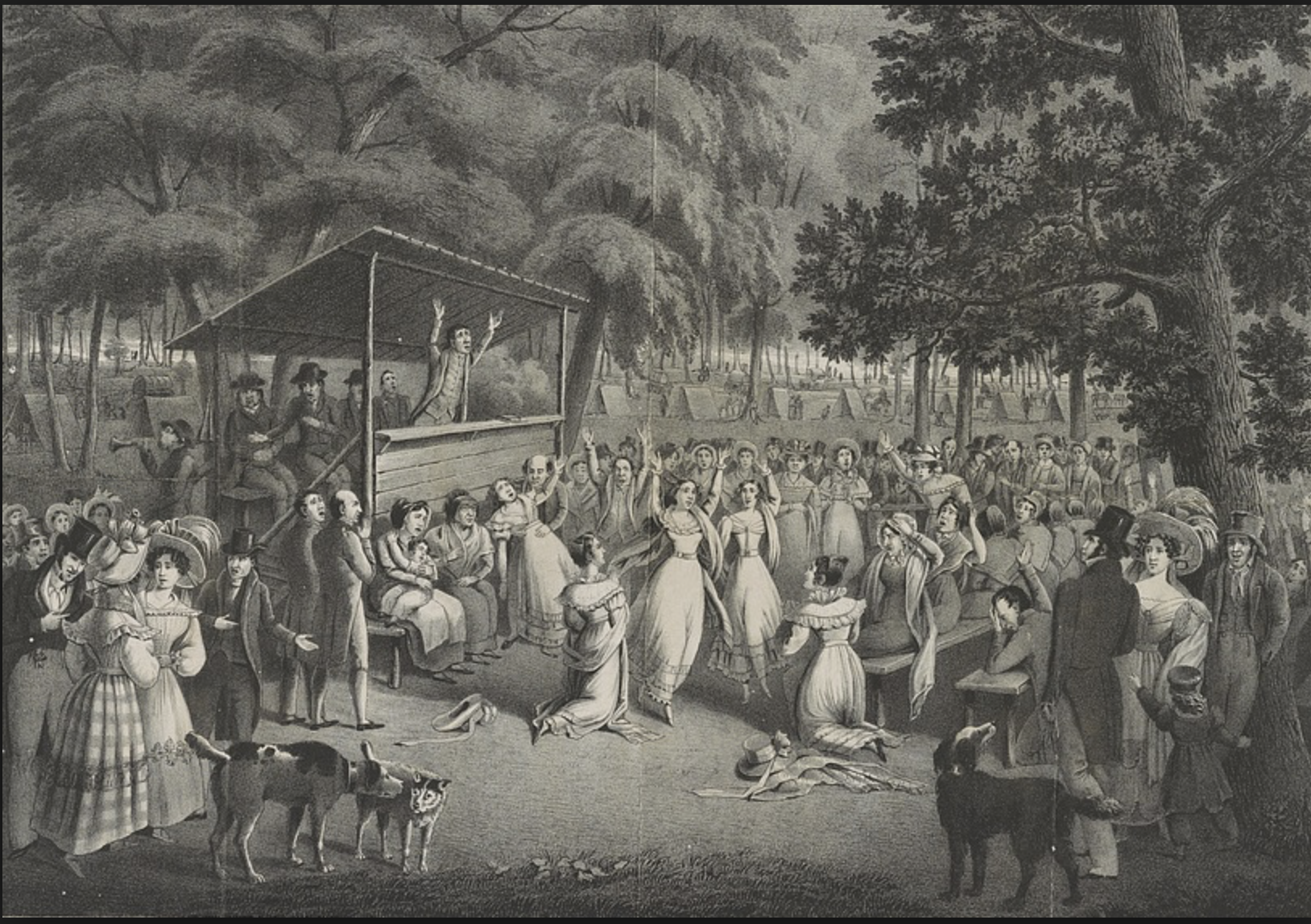

In 1843, John Williamson Nevin (1803-1886), one of the luminaries of the Mercersburg Movement, wrote a book called The Anxious Bench, devoted to countering New Measures revivalism, which he described as consisting of

Seeing revival methods as an innovation bent on gaining converts through emotional manipulation, Nevin emphasized instead the importance of the ordinary means of grace administered by the church through preaching and celebration of the sacraments.

I do not recall any histrionics associated with the altar calls at our relatives’ church, but I do recall something of the emotional high I experienced during these services. I recall something similar occurring at the church-related summer camp I attended at ages 11 and 12.

Reformed Christians in North America were historically divided over New Measures revivalism, leading to an outright split between Old School and New School Presbyterians lasting from 1837 to 1857. The division resurfaced in the 1930s during the fundamentalist-modernist controversy with Orthodox Presbyterians (Old School) going one way and Evangelical and Bible Presbyterians (New School) going another. Old School Presbyterians feared that revival methods would elicit false conversions that would quickly disappear when buffeted by the winds of adversity and the temptations of sin (Matthew 13:20-21). Once the emotional high had evaporated, converts would rest on a false assurance of salvation depending too much on their own decision for Christ apart from God’s electing grace and the work of the Holy Spirit. Revivalism appeared to be based on the false assumption that an unregenerate person could decide for Christ and thereby effectively ensure his or her own redemption—something often called decisional regeneration.

Would bringing back altar calls in churches be a good thing? I doubt it. It has shallow roots in the history of the church, and it is based on questionable theology. If there is to be any sort of call to the Lord’s Table—a term Reformed Christians prefer to altar—it should summon believers to partake of the body and blood of Christ in the Lord’s Supper on a weekly basis. As Psalm 34 expresses it, “O taste and see that the LORD is good!” This is the sort of altar call that has deep biblical roots and ought to be issued whenever God’s people meet together for worship.

Right on! As a “fundamentalist/Evangelical” young person this “church life-style” led me to agnosticism. I could not fine the doctrines as peached – in scripture, and the boogeyman bad god (get saved or hell) had nothing to do with the secular Evil Bad “worldly” society and culture or the real world around me. Thier Christianity had no horizontal thrust, only empty vertical spirituality. Thank Yahweh for a CRC Chapline who gave me a copy of Kuyper’s “Calvinism” and the way of Reformed faith.