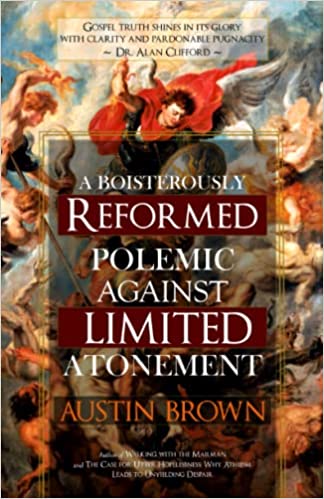

Austin Brown’s A Boisterously Reformed Polemic Against Limited Atonement is a befitting title for such a bold endeavor. Brown challenges the status quo of TULIP orthodoxy right where it hurts most, in the middle. Limited atonement has long been the subject of many pugilistic enterprises in Reformational history, and Austin puts his typewriter to work forcefully in such endeavor.

Introduction

The book argues for a universal satisfaction view of the atonement (1) with the added qualifier that “Christ did not die with an equal intent for all men (5).” Brown seeks to exalt the Lombardian formula to a place of consistency (7), derailing the attempts of limitarians to absorb Lombard as their own. Calvinists of all stripes (cranky Dutch exempted) would affirm that “Christ’s death is sufficient for all, but efficient for the elect (7).” Strict particularists, according to the author, wish to qualify to death the sufficiency of the atonement. They want to treat sufficiency as a potentiality divorcing it from universal expiation (14). But if such sufficiency remains in the realm of potentiality, then there are vast implications for strict particularists, namely that the universal offer of the Gospel is not a legitimate one (16). If Christ did not die for the non-elect, “there is no gospel for them” (20). The free offer, even spoused by strict particularists, fails to be genuine since it is not ultimately sufficient to atone for the sins of the non-elect.

Brown argues, following 17th-century Anglican, John Davenant, that the free offer is only genuine if the “death of Christ is applicable to all men (24).” Davenant sought to find a middle ground between Arminianism and Supralapsarianism. But Davenant is not the only one to oppose limited atonement in its modern definition. Anglican writer and friend Steven Wedgeworth, considering the history of TULIP theology, argues that:

Amazingly, Dabney, Charles Hodge, and William Shedd all distance themselves from theologians like Francis Turretin on the relationship between the decree of God and the cross of Christ, and even go so far as to explicitly reject key exegesis that underlies the “limited atonement” argument found in John Owen’s The Death of Death.[1]

Wedgeworth goes on to make a distinction between high and moderate Calvinists. He argues that the high Calvinist,

“…place the limit in the content of the punishment born by Christ at the cross insisting on only the special will of God toward the elect, whereas the “moderate Calvinists” allow for a general will of God toward all men, as well as the special will toward the elect, and typically place the limitation on God’s effectual calling and application of the cross-work of Christ.”

It’s important to note that the Reformed tradition has built itself on various degrees of atonement language, and there have been exegetical disputes among certifiably Calvinistic figures. Therefore, to accuse Brown of any form of an Arminian spy within the Reformed camp is to miss the diversity inherent in such conversations. It is one reason that I rarely, if ever, associate Reformed theology with TULIP. Such associations minimize the depth of Reformed history by trivializing Calvin and Bucer’s rich sacramental theology and the profound political theories of the theonomic Puritans, not to mention the liturgical theology of the German theologian John Williamson Nevin, who sought to re-articulate a rich ecclesiastical vision from Calvin.[2] To limit Reformed theology to individual soteriology would be to mock the broad themes and emphases of the Reformation.

Brown makes helpful observations throughout, working carefully through key universal texts and showing that the exegetical gymnastics done by some do not comport with the nature or context of the passage. They cannot be limited when they are naturally meant to be universalized. Again, Brown is merely stating that there is a sense in which the atonement reaches the elect and another sense in which it reaches the non-elect; but in both cases, the offer is free and genuine to all.

To put it succinctly, “Forgiveness is truly available because God is willing to forgive in Christ (144).” Brown further makes good points concerning I Timothy 2:5-6, 2 Peter 3:9, and other texts that indicate a universal scope of the atonement. Such observations cannot be refuted in my mind, and there is sufficient horsepower among the Reformed to defend such a thesis. I would dispute several exegetical conclusions, but I affirm with Brown that these passages have been overly stretched under the purgatory of strict particularists.[3]

To sum up, Austin Brown is not committing reformational harlotry; neither is he moving away from green Calvinistic pastures, but he is staying certainly within the streams of living waters in Geneva and Scotland—although admittedly not in the Netherlands.

General Suggestions and Particular Disagreements

What follows are areas for further consideration where differences arise between us. I mention them as points of clarification, inquiry, and perhaps linguistic preferences based on my own theological and academic inclinations.

First, Brown would be better served and more carefully understood if he were to speak of limited atonement within the paradigm of efficiency alone. High-Calvinism stresses the importance of election upon the decretally chosen. Thus, instead of bidding “Limited Atonement” adieu, I would seek to work within that paradigm, stressing that there are variegated forms of L’s and that his interpretation comports more soberly with the Dabney school of thought than Turretin or Owen.

I believe it is more fruitful to use a common and accepted language to make differentiations than to usurp current use and substitute it with something more fanciful like Classic Calvinism. Of course, we all want to be as classical as Coke, but such distaste can turn off immediate opportunities for persuasion.

Further, some high-Calvinists also affirm that God “desires the salvation of the non-elect” (64). Some attempt to make distinctions to explain better the universality of the offer and the efficacy of the atonement. John Piper observes that the decretive will and preceptive will, voluntas signi (will of sign) and voluntas beneplaciti (will of good pleasure) are helpful ways of explaining the desires of God in the Bible. Others argue within a philosophical paradigm to harmonize the genuine biblical language of God’s love for the non-elect. And while asking whether the Genevan pastor held to limited atonement would be anachronistic, we should still remember that Calvin allowed for such language of universality without much concern:

“… we must understand that as long as Christ remains outside of us, and we are separated from him, all that he has suffered and done for the salvation of the human race remains useless and of no value for us.”[4]

Calvin affirmed the conditionality of the atonement, for no one is saved until they are given union with Christ. As Presbyterian minister Mark Horne, notes, “It is not the atonement which is intrinsically ‘definite’ but the work of the Spirit.”[5]

These are alternative explanations among the limited atonement theologians. Thus, I believe it is more fruitful to maintain the language while acknowledging that there are different attempts to explain how to make sense of the Lombardian formula concerning the sufficiency of the atonement.

My argument here is more along the lines of rhetoric and how to effectively administer the vast repertoire of opinions among the Reformed tradition on this complex topic.

Second, the use of “Hyper-Calvinism” to illustrate certain exegetical tricks among, generally, Reformed Baptist scholars is unhelpful (87). It fails to deal with the concern among some of these men that we lose something when we generalize atonement language. While we may disagree with the concerns expressed, the high-Calvinist’s attempts seek to protect Christ’s death from misuse and abuse.

Further, practically, I would suspect that none of these theological inclinations, or as I prefer, tendencies, would lead to what was once somewhat present among those who did not believe in the evangelistic endeavor among the pagans. I do not believe that men like Francis Turretin or modern-day Reformed Baptists are near the hyper-Calvinist inferno either theologically or practically.

Third, it may be more fruitful to focus on the atonement through the categories of covenant and decrees. Covenant implies conditionality, which seems to be what Brown is arguing. Covenantal conditionality means that the benefits of the atonement may be received freely by those who believe. Some of this came to the forefront in chapter 18, but more elaboration is needed. Much concern in these discussions is that we view atonement through the monolithic lenses of theology when theology is much more at ease perspectivally.

The atonement of Jesus was/is sufficient for even those who will apostatize since it bore genuine fruit (Heb. 6). Still, such fruit was trampled upon (Heb. 10). We can also affirm that no elect decreed in eternity past will fall away or be outside the efficacy of the death of Jesus. The atonement of Jesus brought true enlightenment to those who were in covenant with God but apostatized like Judas, and it brought true and everlasting life to those who will die and dwell with Christ forever. The atonement can cover all in these senses because the atonement can bring blessings upon the obedient and curses upon those who forsake the assembly (Matt. 18). Thus, atonement language cannot be divorced from sacramental or ecclesiastical language.

Fourth, almost exclusive attention is given to Pauline texts to the detriment of the atonement theology played out in the Gospels. Of course, one cannot say everything, but I would seek to incorporate the Gospel of the kingdom into any atonement thesis. The kingdom played a fundamental role in shaping the beginning and the end of the Jewish age in AD 70. Thus, atonement theology, in some sense, must also do justice to the end of the kingdom era under Jewish idolatry and the new Israel of God post AD 70. In sum, atonement theology must incorporate eschatology beyond anthropology.

Finally, those universal passages (John 3:16, in particular) must fall into a Warfieldian scheme. While Warfield was mentioned briefly in a footnote (47), there is much more than first meets the eye. For Warfield and modern-day postmillennialists like myself, the love of God, even through the lens of the atonement, has a robust eschatological component. It follows the trajectory of cosmic language used in the Torah and the prophets and re-asserted by Jesus. Even John 1 begins as a new Genesis committing those under John’s tutelage to see Jesus restoring and renewing a new cosmos under the Law-Word of Yahweh.

Thus, universal passages have anthropological and individual soteriological components, but I am persuaded that eschatology is the very purpose of John’s discourse. Further, if John’s Revelation is John’s Olivet Discourse, then truly, the Gospel of John 3:16 falls squarely within the realm of eschatological glory.

The world of John is the oikoumene of the ancient world looking for a cosmic renewal where the present world is passing away, making room for a new world so loved by the death of King Jesus, who rules and reigns over Nicodemus and the new born-again cosmos.

Conclusion

Austin Brown’s work was filled with happy truths, scholarly use of resources, fun puns, witty and boisterous scoldings of strict particularists. It seems that the case for a genuine differentiation of the impact of the atonement upon the just and unjust can be made and was successful in this work.

I am not persuaded that we must toss limited atonement or that it has been highjacked by strict particularists. In fact, it seems that Calvin can give with one hand and take with the other because Calvin saw that there are various ways to speak of the atonement while strongly affirming an efficacy among the decretally elect and all sorts of benefits for the apostates and a certain extent those who have never tasted of the heavenly gift.

The book succeeds in opening the atonement discourse to readers only familiar with podcast theologizing. In this sense, I think it is the book’s most significant benefit and why I encourage a fair read without the vitriol but with whiskey and cigars in typical Calvinist tradition.

[1] https://biblicalhorizons.wordpress.com/2008/01/31/the-synod-of-dort-and-the-complexities-of-being-reformed/#_ftn3

[2] It is worth noting that Calvin himself gave more room to his ecclesiology than to individual soteriology in his Institutes.

[3] I would distinguish strict particularists from regular particularists. Strict particularists fold the text into a one-size-fits-all, while regular particularists allow the text to treat both limited and universal applications.

[4] III, 1.1, Ford Lewis Battles, tr (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960), p. 537

[5] http://hornes.org/theologia/mark-horne/why-will-you-die#47b

Brother Uri, what would you have done for my family if my you made my head explode? My goodness that was close…

Haha. tell me more 🙂

That was super deep. I had to read every other sentence a few times to get it. And I think I get the jist of it but man…. a lot of big words. I really had to put my thinking cap on for this one. I embrace TULIP theology and believe in the total sovereignty of God. I think I really like the idea of God’s atonement being sufficient for all but efficient for only God’s elect. That was a good distinction. Our God does what He pleases. He chose Abraham and not John Doe. His ways are not our ways. And we must be okay with that. Clearly, scripture teaches the idea of Limited Atonement. Great article brother. Your content is so helpful.