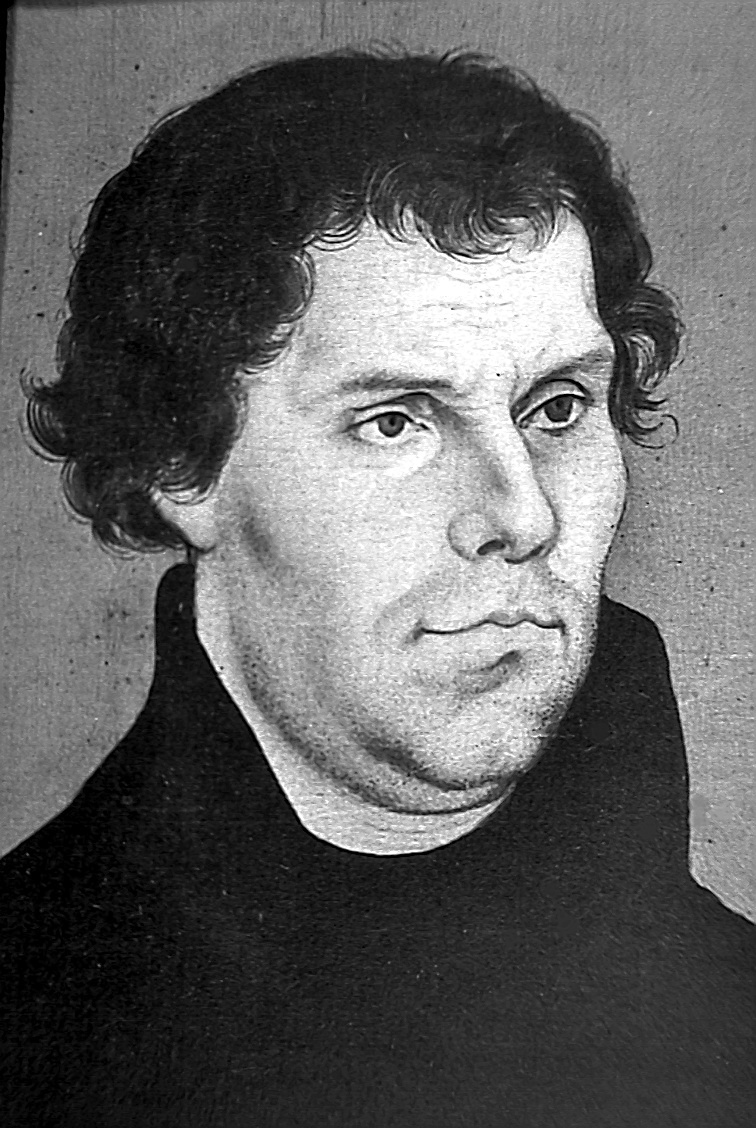

As we approach the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, Martin Luther’s 95 theses remain the most revolutionary document in Western History. Luther’s attempt to begin a conversation about indulgences provoked an ecclesiastical and sacramental revolution. This revolution reverberated through the last 500 years and will continue to do so for many centuries to come. But Luther’s theses served the purpose, unbeknownst to him, of catapulting this Augustinian monk to the center of the church’s disputes of the day. Spurred by a prolific genius, this trilinguist sought comfort in the liberating power of God’s revelation.

Luther wrote on a host of issues, but particular to his concerns, was a hunger to recover proper worship in the Church. Martin Luther’s On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church[1] is a biblical examination of the seven sacraments of the medieval church. The Luther-revolution began as he opened his Bible and examined the practices of the Church in light of scriptural teaching. The reformer was compelled “to become more and more learned each day” implying a continual testing[2] of these practices in light of his voracious commitment to the Scriptures.

For Luther, the Papacy is a “kingdom of Babylon,” twisting the clear articulation of Holy Scriptures.

In his treatise, he begins by addressing the Lord’s Supper. In direct fashion, Luther viciously attacked the church, claiming its “tyrants” were denying the laity reception of both elements. Luther argues from Paul and the Gospels that the Lord’s Supper belongs to the entire Church.

Furthermore, The German Reformer observed that the Eucharist was also misunderstood. Fixed in the Aristotelian[3] philosophy of the day, the medieval church contended that at the moment of consecration the bread and the wine change in substance becoming the body and blood of Christ. This doctrine of transubstantiation is a “counterfeit Aristotelian philosophy”[4] not found anywhere in the Scriptures. Luther’s alternative to the dogma of the church[5] asserted that “Christ’s body is at the right hand of God….The right hand of God, however, is everywhere…. Therefore, [Christ’s body] surely is present also in the bread and wine at table.”[6] For Christ to be a gracious host, then he must be present bodily.

Second, Luther believed that “baptism is of the highest advantage.”[7] He did not see the church of the day perverting this sacrament as much as others though he later would protest the extravagant ritualization of the sacrament. He asserts that in baptism the divine promise of salvation is given. The minister should not assume that he baptizes in his own authority, but “in the name of God.”[8] This qualification offered a subtle but crucial distinction in Luther’s theology.[9] Luther further argues that baptism signifies death and resurrection, the complete justification of the sinner (Rom. 6:4). Luther believed that baptism cannot be separated from faith. Indeed the only sin that can undo the grace of baptism is the sin of unbelief. Interestingly, though Luther speaks dogmatically on many of these issues, there are questions where Luther seems silent. For instance, concerning whether an unborn child can be born again, he observes that it is a “question to the decision of the Holy Spirit.”[10]

Third, Luther addresses penance. This forms the sacramental triad for Luther; that is, the acceptable sacraments of the Church.[11] Still, the gifted pen of Brother Martin is consistent in his reassessment of these medieval sacraments. Luther stressed that penance serves as a sign to remember one’s baptism. Like the Lord’s Supper and Baptism, penance was also a gift, but the church’s use of penance as an attempt to trust in “your own contrition…or sorrow”[12] was misplaced. Luther believed in the validity of penance as a sacrament, as long as it is acted in faith. The benefits of penance do not stem from any good of our own, but “the truth of God and our faith.”[13]

The additional four sacraments of the medieval church are rejected by Luther. It is not so much that Luther denies their practice as rites of the church, but he rejects that they are sacraments instituted by Scriptures. As Luther himself defines:

To constitute a sacrament we require in the very first place a word of promise, on which faith may exercise itself.[14]

However, Luther argued, Christ never “gave any word of promise respecting confirmation.”[15] While Christ laid hands on others, there are no promises attached neither is there salvation in such a ritual, which a sacrament promises.

Luther’s dismantling of the medieval sacraments insists that matrimony, though providing great benefits, cannot be understood as a sacrament. There is no promise of grace—in its divine efficacious sense–[16]for a man who takes a wife. Further, a sacrament is something distinctly reserved for the Church. And since unbelievers partake of the gift of marriage there remains no reason to see matrimony as a sacrament.

The church was captive to another supposed sacrament, namely, concerning orders. Luther makes his point rather quickly in the first line: “Of this sacrament the Church of Christ knows nothing; it was invented by the church of the Pope.”[17] Once again, Luther maintains the same argument as prior. Holy orders, like many other rites, have no promises attached to them and thus are not to be considered a sacrament. Luther grounds his rejection of orders on the basis of theology and the consistent voice of the church.

Finally, arguing from James 5, the medieval church attached the title “extreme” in extreme unction to refer to cases where life is at peril. This “sacrament,” they argued, was only to be administered in extreme circumstances. Assuming (for argument’s sake) James wrote this epistle, Luther claimed that only Christ could attach a promise to a sacrament and that apostolic authority was not sufficient to do so.

This short treatise was written with the intention of being used for “future recantations.”[18] Luther understood that he would be continually charged with heresies and urged to recant. However, Luther believed that obedience to Jesus Christ meant standing on the truth of God’s holy word.

Evaluation

While a thorough evaluation is impossible, I wish to make a few observations concerning the nature and method of Luther’s treatise.

First and foremost, it is worthy to mention Luther’s strong emphasis on the centrality of Scripture in worship. Practices that do not comport with the biblical agenda are to be rejected. Luther’s Reformation was indeed a reformation of worship.

Second, Luther’s evaluation of the medieval church was undoubtedly severe. We should not judge Luther’s antagonism, but understand his context required a particular and peculiar pugilism of which Luther’s pen was a great champion. At this period, the Reformer had already received the strong condemnation of the church. His opposition to indulgences was well known, and his critics had already made clear their distaste for Luther’s agenda. His response soured the medieval church’s table wine.

Finally, Luther’s vivid descriptions and disagreements serve as the genesis of a return to the hermeneutic of the church fathers. The captivity of the church stemmed from captivity to a relatively recent tradition; innovations not grounded in ancient sources (ad fontes). One could say that Luther attempted to give sight to the blind and make the lame to walk. Alas, the medieval church chose blindness and biblical paralysis.

Martin Luther’s emphasis on the priority of faith is a stark contrast to the medieval church’s emphasis on merit. For Luther, the sacraments needed to be exercised by faith and experienced by faith and that faith is a gift from God, not of works lest any man should boast.

[1] All quotations are from “On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church.” Kindle edition.

[2] I John 4:1.

[3] Luther refers to Aristotle as a monster.

[4] On the Babylonia Captivity of the Church. Kindle Edition.

[5] Later coined con (with) substantiation.

[6] Martin Luther ‘That These Words of Christ, ‘This Is My Body,’ etc., Still Stand Firm Against the Fanatics, 1527’ Luther’s Works Volume 37: Word and Sacrament III Robert H Fischer ed and trans (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1961) , Luther ‘This Is My Body’ pg. 63f Note: Matters

[7] On the Babylonian Captivity.

[8] Ibid.

[9] We should note Luther’s opposition to medieval forms of sacerdotalism.

[10] On the Babylonian Captivity.

[11] Luther later would adopt only two of the three.

[12] Babylonian Captivity.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] I wish to add that grace is provided in marriage, but grace in its common gifts; general grace provided in fidelity, love, worship of God, and mutual edification and encouragement.

[17] Babylonian Captivity.

[18] Ibid.